Until recently, Tulum was a small, quiet town. On the Caribbean side of Mexico, close to Mayan ruins, few cabanas lined its broad white beach and these drew mainly archaeologists. But targeted for tourist expansion with an eye to fashioning eco-resorts inflected by Mayan ontology and design, Tulum has become the head of a newly founded municipality and, now with a population of 20,000, is programmed to grow to 250,000 in the next decade. Building is massive. Such as the exclusive city Aldea Zuma, an ecological island that will allow those inside to commune with nature, in luxury facilities, built on exploited ejido (indigenous) lands, and constructed by an itinerant and underpaid labor force.

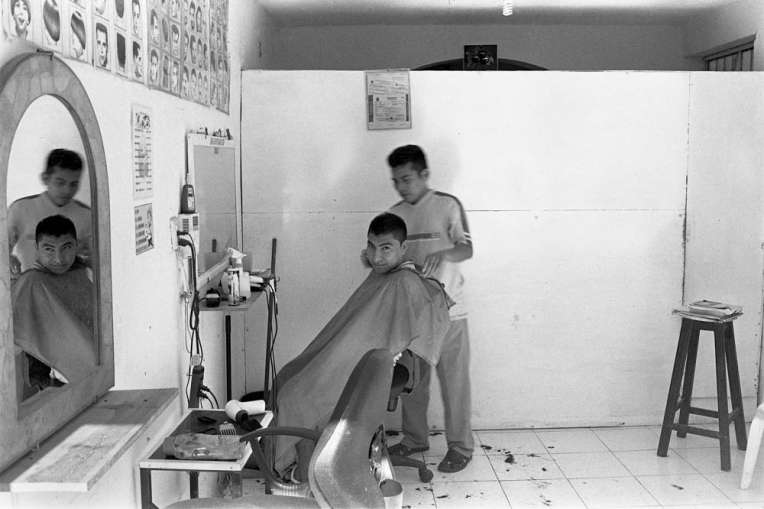

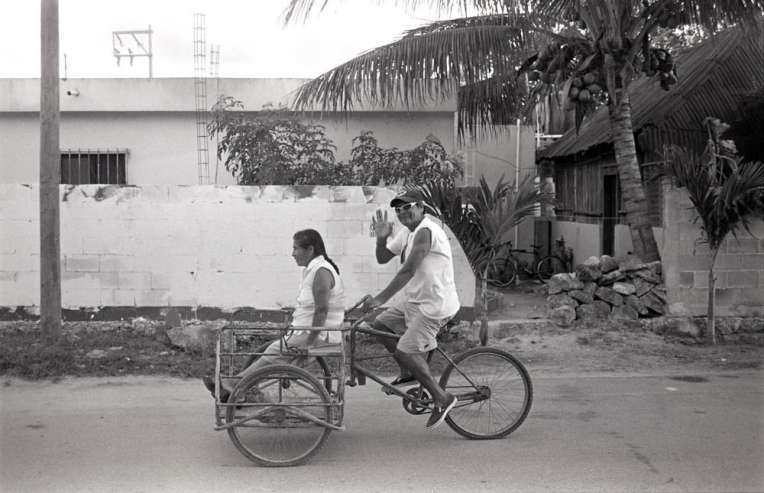

The lives of these workers, a true precariat, are the subject of this photo essay. The photos aim to capture a moment, a slice, an encounter, to invite viewers to imagine how people, so precariously pitched, craft a semblance of life in the everyday. Of central concern to Rabasa and Cuelenaere is what, borrowing from Francois Hartog, they call presentism: a condition of temporality that, rooted to the here and now of getting by and making do, remains always grounded in the present. Seeing this as a marker of precarity, a condition that affects the totality of life and not just the labor or work of the precariat, Rabasa and Cuelenaere use photography to bring viewers into this presentist zone of an uncertain everyday. Exploring with their Nikon F2 and Hasselblad 500/C cameras the affective worlds of people returning from work, heading to one-room homes of cardboard recovered from debris, cooking and washing outside, greeting neighbors or dressing for church, the photographers trace the fragility of lives without future and past. What they also show is that, even amid such uncertainty, smiles also glimmer suggesting something else: the potential for political insurgency.

Review Process

This photo essay is the first to have gone through the Photo Essays section’s experimental peer-review process, and the section’s editors (Michelle Stewart and Vivian Choi) wanted to briefly explain its intent.

Our goal is to highlight the innovative ways that photography and visual representation are being taken up anthropologically, and to do so alongside a text-based journal at the heart of the discipline. We also aim to provide a space where a photo essay can be peer reviewed. By hosting the photo essays on the Cultural Anthropology website, we want to take advantage of the site’s technological capacities to allow the pieces to shine and a dialogue to emerge.

As part of this commitment to dialogue, we have created a hybrid peer-review process that is closed (double-blind) when the review is conducted and then opened (with author and reviewer revealed to each other) when the author begins their revisions. The goal is to put reviewer and author in direct discussion beyond the usual confines of double-blind review. Once the essay is published, the discussions between author(s), reviewer(s), and editor(s) can then extend to the reader/viewer, through interactions on social media. We embrace the traditional peer-review process and its promise of rigorous engagement, but also want to push it into the open and to adapt it, as needed, for each essay we publish.

The review dialogue appears below, after the images and essay text.

Download “Imagining Precarious Life in Tulum, Mexico” by José Rabasa and Laurence Cuelenaere as a pdf booklet.

Photos

Essay Text

A singular visual scheme defines the precariousness of Tulum: abandoned yards, old tires, trash, a few chickens or dogs running around, and the smell of excrement. Blue, red, pink, purple, violet garments hang from clotheslines in the yards, lending movement and structure to these apparently disordered scenes. Most of the homes consist of one room with a couple of hammocks, a fridge, a television, and a bed for the parents. The homes are often made of cardboard and plywood, of found debris. In the mornings and in late afternoons, people walk through their neighborhood on their way to work, to supermercado Willis, or to attend service at one of the many evangelical temples. They look into each other’s yards and salute friends and family. Women cook outdoors and use their washing machines installed in the yards. As we walk around with a camera, conveying our intent to photograph, we become one more element of this visual scheme. While the photographs capture moments of the interaction between the photographer and the subjects, the open flow of our writing purposely conveys the experience of walking around town engaging people in conversation. While the text does not explain, interpret, or draw ethnographic knowledge from the photographs, the photographs also do not illustrate the text. We abstain from using captions to underscore the collective memory embedded in the narratives and the force inherent to the presents captured by the photographs.1

Until the mid-1970s, Tulum was a small, quiet town. On the Caribbean side of Mexico, close to Mayan ruins, its broad, white beach had few cabanas and these buildings drew mainly archaeologists. Targeted for tourist expansion, Tulum has become the head of a newly founded municipality and, now with a population of 20,000, is programmed to grow to 250,000 in the next decade. Over the years, it has seen spurts of growth: first, eco-chic small hotels along the beach; more recently, the Aldea Zama, an artificial city that will allow those inside to commune with nature. The infrastructure needed to absorb this growth remains to be built. The planned exclusive city of Aldea Zama—El Corazón de Tulum in the promotional pamphlets—already has an infrastructure laid out, which includes a street called La Quinta Avenida that will be reserved for luxury stores. On the other side of town, the government-sponsored lending system for worker’s housing has already traced the streets for building pigeonhole apartments. The expectation of growth is visually manifest in the large, empty parking lot outside the recently inaugurated Chedrauri, a chain of megastores known for its disregard for the ecologically fragile terrain where many of the stores have been built. Four gas stations have been added. The population growth of Quintana Roo, the state where Tulum is located, has been fueled by immigration. It is said that thousands have been seduced (when not forced by riot police or paramilitaries) into fleeing from lands that belonged to their communities, often in the form of ejidos, communal lands distributed by the state. To date, the men and women who told us their stories have not returned to their rural homes in Tabasco, Veracruz, and Chiapas. They recalled these places with love and nostalgia. Women spoke of how they cried in the dark, terrified in their solitude, when they first arrived in Tulum. Others recalled the displacement from Cancun, first to Playa del Carmen and later to Tulum—places where they once could swim at endless, deserted beaches and listen to the flocks of parrots in the forest, spaces from which they are now barred. The lucky ones have avoided alcoholism, drug addiction, and suicide. The index of suicide in Quintana Roo is the highest in Mexico. And yet people smiled when they talked to us.

We are conscious that the images will invite the viewers to wonder how is it possible that people can smile while living under poverty, pollution, and displacement—all consequences of modernization and the creation of spaces for our delight. Other viewers will not even be surprised by the banality of poverty. The aestheticization of poverty and suffering haunts the photography of precarious life. Capturing smiles and laughter carries the burden of trivialization: how can the poor laugh or smile back under the oppressive states in which they live? One cannot but offer an oblique response to the why of their smiles. It is as if, in smiling, they evoke centuries of oppression and rebellion; as if precarious life, survival on a day-to-day basis, was the ground of collectivity. The shared present of the taking of photographs, of conversations, the exchange of smiles—for we also smiled—entailed communion, a commonality of purpose, hospitality. There was an opening that invited us to sit and converse. Theirs was a hospitality, perhaps an ethics and politics of friendship, that should not be confused with the charitable acceptance of the other by those in power; rather, the smiles were gifts with no expectation of reciprocity. For they were not dismissive grins, expressions of tolerance for our intrusion into their daily lives and intimate thoughts. The stories we invoke, however, were hardly a smiling matter.

Concepción and Tania first came to the magical Riviera Maya in 1973 to work on the construction of the megatourist complex of Cancun. In the history of Cancun, one reads that it was one of five places that were officially approved for development in 1969 by the Bank of Mexicol; the other four were Ixtapa, Loreto, Los Cabos, and Huatulco. The first INFRATUR (Trust for the Promotion of Tourism Infrastructure) technicians arrived in 1970. Concepción and Tania were among the first imported laborers. Concepción was part of the work crews that were brought from Tabasco, Chiapas, and Veracruz under the auspices of trabajo y techo—work-and-roof—contracts. He recalls dynamiting the forest. Tania remembers living in fear of rape, hiding at night in an environment plagued by femicide. She cooked for the workers in temporary kitchens set up in the camps. Other women were less fortunate, having been forced into prostitution. In 2006, Concepción and Tania moved to Tulum from Playa del Carmen in pursuit of the quiet of nature that was once enjoyed in Playa. We later learned that they had returned to Playa, apparently after being fired from the hotel where they worked. Hotels use short contracts of eighty-eight days to avoid the law that requires granting benefits after three months of employment. These work conditions are not unique to Tulum—or Mexico, for that matter.

To understand the temporality of the smiles we captured photographically and in conversation, we may benefit from François Hartog’s (2012) discussion of the French sociologist Robert Castel’s use of the term precariat, a composite of precarious and proletariat. It is in this state of vulnerability that the distinction between a past, a future, and a present disappears in what Hartog has named présentisme. The concept of the precariat enables Hartog to draw a distinction according to the place one occupies in society. Presentism implies two modalities in the experience of time. On the one hand, one finds acceleration in the neoliberal belief of inexhaustible expansion, while on the other, one finds a decelerating present without past as lived by the precariat: the immigrant, the exiled, and the displaced (Hartog 2012, 17). This partial list conveys the wide range of experiences of presentism, of a closed future among the precariat in Tulum. And yet the possibility of radical politics, of a utopian impulse, may also come into being in a present, in terms of a temporality that Walter Benjamin (1969, 263) defined in contradistinction to historical progress as the jetztzeit, “‘the time of the now’ which is shot through with the chips of Messianic time.” The smiles and laughter captured by the photographs and the voices invoked in this written text seek to convey the potential for insurrection, the joy of rebellion. Our conception of the precariat differs radically from Guy Standing’s (2011, 1) warning: “They are becoming a dangerous class. They are prone to listen to ugly voices, and to use their votes and money to give those voices a political platform of increasing influence.”

If, for Hartog, the precariat is a consequence of neoliberal, market-oriented policies, in Tulum and, we would add, in the Third World in general, the condition preexists the financial and political crisis often cited as marking the beginnings of neoliberalism. This does not mean that neoliberal policies have not affected regions of the world where Fordism, just to mention one model, was never implemented or generalized to the majority of the population. Precarious life is not a recent condition that can be dated by the financial crises in the First World. The photography of Nacho López, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, and Hector García, to limit ourselves to the most well-known, documented precarious life in the ciudades perdidas, the slums of Mexico City, during the first half of the twentieth century, when there were the first massive migrations from the countryside. This is not to say that neoliberal policies have not exacerbated the plight of the precariat. We cannot underscore this more.

We may mention the modification of Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution during Carlos Salinas de Gortari’s presidency (1988–1994), which opened the legal channels for the sale of ejido lands. The establishment of ejidos was first conceived for land distribution in Mexico after the revolution of 1910. Under the ejido, families control the plots while the land is legally held by the community. Thousands of petitions of ejido lands remained pending when Salinas reformed Article 27. Salinas’s modification constituted an affront to indigenous people throughout Mexico. It is often listed as one of the main factors leading to the Zapatista uprising in 1994, on the eve of the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). This was one of the many changes that completed the turn to neoliberalism characterized by the privatization of state-owned industries and the encouragement of foreign investors that had been initiated by his predecessor, Miguel de la Madrid (1982–1988). Low productivity of farmlands, which actually means the disregard for profit, figures as one of the main justifications for the reform, for easing the sale of ejido lands. This argument completely disregards indigenous forms of life, particularly the Mesoamerican culture of maize now threatened by NAFTA, which stipulated a timetable for opening the border to the importation of inexpensive corn grown in the United States. The desirability of the lands for development geared toward the tourist industry underlies the sale of ejido land in Tulum. After the reform of Article 27, rule by consensus gave place to majority rule; attaining 51 percent eased the legal channels for the sale of land and the recognition of the buyer as an ejidatario. Arriving at consensus could always be manipulated; however, it was much more difficult than attaining the mere majority now in place. If we single out the destruction of el campo, a shorthand for the self-sufficiency of the ejido and communal lands, it is not to limit the effects of neoliberal policies on land ownership.

Among the people we spoke with, there is the temporality of the ill with limited access to health services, of those in jail without recourse to justice, of political actors crushed by insurmountable corruption, of indigenous people dwelling in elsewheres to modernity. Consider a twenty-nine-year-old mother without a source of income, caring for five children; a son fighting to liberate his unjustly imprisoned mother; an old couple preparing pozol on a daily basis in a isolated backyard to sell in the evenings; a lawyer defending an innocent man accused of murder, who lacked the resources to file a recurso de amparo (an instrument for protecting constitutional rights); a young man reading a newspaper in a makeshift bicycle shop; an evangelical minister who heals the community of the vulnerable; a Maya priest recollecting the nineteenth-century insurrection of Chan Santa Cruz, the so-called war of the castes.

It has often been argued that the time of photography is the present. And yet what is meant by this use of presentism varies widely: from Roland Barthes’s (1981, 77) claim that photographs incessantly assert that-has-been, “the irrefutably present, and yet already deferred”; to John Berger’s (1991, 51) reading of Paul Strand’s unique sense of duration as capturing the “historic” moment, never more manifest than in the willingness of the subject to say I am as you see me, wherein the “the exposure time is the lifetime.” The photographs of Tulum differ from the historic of Berger’s reading of Strand and the phenomenological instantiation of Barthes’s reflections on photography in that they seek to evoke a precarious present that conveys the fragility of lives without past and future. The recorded stories do not necessarily correspond to the people participating in the making of the images, and yet these recounted lives compose collective memories irreducible to the individuals. The men and women we spoke with and who opened up to the photographer made their vulnerable and precarious existence manifest. For one becomes vulnerable while telling one’s intimate stories and lending one’s face without asking for anything in return, fully conscious of participating in the making of a photograph.

We used a Nikon F2 and a Hasselblad 500/C camera. Whereas the Nikon was readily identified, leading subjects to salute, the Hasselblad appeared a strange artifact leading subjects to ask what it was or to tell stories about uncles who used cameras with winding cranks. These cameras became agents that defined the situation and depth of conversation. In the exchange of gazes, we found a tacit acceptance that nonetheless involved surprise and fluidity. The Hasselblad, with a waist-level viewfinder, enabled us to make portraits at a slow pace that allowed for intimacy. The subjects were full participants in the composition of the pictures. We played with their spontaneous posing, from stiff postures to playful leanings on windowsills, to mothers herding children into the frame. Little would be gained from looking for data—if any is found, the viewer should consider it the result of the photographic optical unconscious (Benjamin 1999). The Hasselblad lends itself to making static, dense images, but even in the fluid wide-angled photographs using the Nikon, the objective was not to record information but to explore worlds of affect—states of joy, desire, melancholy, and ennui that the photographs may invoke with the aid of the recorded stories.

The precariat and the presentism of the smiles—invoked in the juxtaposition of stories of oppression and photographs of seemingly unaffected subjects—encompass a wide range of actors. In imagining precarious life in Tulum, we have conceived ourselves as forming part of this precariat. The people we engaged in conversation were never conceived as an other to be documented but as actors in a shared political field. Even when we have assumed the role of writers and photographers, the recorded voices and imprinted light testify to the subjects’ agency. The stories invoke a collective memory for imagining the lifetime of the subjects with whom the photographs were made. The precariat’s experience of presentism conveys the burden of a time with a closed future, and a past filled with nostalgia and the recollection of fear and apprehension. The future is blocked, and yet the smiling and laughing subjects convey the potential for insurgency.

Notes

1. We have drawn from a wide range of writings in our project of photographing and writing about precarious life in Tulum. In James Agee and Walker Evans’s (2001) Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, we found an instance where photography and writing create parallel, independent texts based on a common experience. In our reflections on affect, we have benefited from Kathleen Stewart’s (2007) experimental ethnography in Ordinary Affects. Like Stewart, we do not pretend to represent voices, but rather to evoke the many conversations we held with the people we spontaneously engaged in the streets while photographing. Jane Bennett’s (2010) Vibrant Matter has offered a way to conceptualize the agency of inert objects. From Michel Serres (2008), we learned how to understand writing and photography as involved in transitions from hard to soft and from soft to hard. Writing does not merely produce information, but carries an echo of our voices and the voices we invoke. On the other hand, photography turns hardness (light, bodies, situations, movement, etc.) into softness (the image, representation) not intended to record information, but to create hard objects with a life of their own, vibrant agents in se. Michael Taussig’s writings, most recently What Color Is the Sacred? (Taussig 2009), have inspired us to tell theoretically informed stories that remain unburdened by theory.

Review Dialogue

Below, Stewart and Choi have thematically organized segments of the reviewers’ first-round comments, their own editorial suggestions, and the responses of the essay’s authors.

Frontloading Theoretical Claims

Reviewer A: “I would like to see the authors move the very last sentence of the essay, where they actually delineate their “objective,” to the beginning, so the reader is not fooled into thinking that this is traditional ethnography. I don’t think that working in rumor is all that unique. As cultural anthropologists, our currency is gossip: our job is to figure out which rumors align with each other and which ones do not, in order to accurately present a broader narrative.”

Reviewer B: “I think the text could be strengthened a lot by bringing the compelling stories that follow from page 5 up to the beginning. These are the stories that hooked me as a reader. An author needs to work twice as hard to get a reader to pay attention when displaying images along with text in an online format. The impulse is to skip the text entirely if the story isn’t immediately compelling. In this case, the ethnographic importance is really in the juxtaposition between the images and the text, so it is important that the viewer also be a reader. Bringing this hook to the front might solve the problem. Also, the second compelling question (why take photographs and write about Tulum?) is very near the end of the writing. I think the work can be strengthened by either placing this question and subsequent paragraph first or placing it immediately after the written ethnographic snapshots.”

Editors’ suggestions: “In order to strengthen the overall submission—of both image and text—the theoretical aims highlighted in the written essay need further clarification and expansion. As both reviewers suggest, the theoretical claims of the essay, while compelling, need to be stated up front and earlier in the text.”

Authors’ response: “The first item that you mention is the need to state the theoretical claims up front and earlier in the text. We cannot agree more on that recommendation.”

Use of Language

Reviewer A: “I’d like to see the authors rethink their ideas about ‘taking images’ . . . and consider the term ‘making’ images, because if they are working with the subjects and the subjects understand the stakes involved in photography, of the power relationships and the ideas of representation, then it’s a group process. Photographer and subject are each actors and it’s a collaborative process, not a ‘taking’ process.”

Reviewer B: “I suspect that the authors want to communicate both a sense of ‘imagining’ and ‘image-ing’ (or making images) with the term imag(en)ing. If this is the case, it would be good to explain the significance of both of these ideas and why it would be useful to use them together. Making an image is a kind of imagining. The photographer uses her imagined idea of who/what she is photographing at the same time that the viewer is using the photo to imagine the lives of the people depicted. Furthermore, the strength of the essay does fall within this tension. It is not often that we see images of poverty, displacement, and pollution that have such comfortable, smiling faces and that ask nothing of the viewer. This is important. I am skeptical that the postmodern term imag(en)ing is the best way to communicate these ideas together (if only for the reason that imagining is spelled with an ‘i’), but if the writers prefer to keep the term, I would suggest that it be unpacked to communicate more precisely why they think the term/idea is meaningful and useful.”

Editors’ suggestions: “The title of the article needs to be further unpacked and returned to in the essay. Both reviewers question the play of words with imag(en)ing, and share a concern about the term’s meaning and the theoretical work it does.”

Authors’ comments: “Reviewer B appreciates the distinction of imagining and image-ing implicit in the title of our essay. He or she is right in calling our attention to the unnecessary, postmodern-inspired term. The neologism imag(en)ing simply doesn’t make sense because the parenthetical ‘en’ does not work. We can be more direct by using imagining and making the distinction between imaginings and image-ing, as image-making, explicit in the text.”

Tightening Theoretical Arc

Reviewer A: “The theoretical frameworks are not labored, which is refreshing, for the 1.5 pages or so that [the authors’] dedicate to ‘theoretical framing.’ They present their interesting idea of an ‘affect of experiencing impunity’ and explain the neologisms from Castel and Hartog, and then move on into the piece without returning to these ideas or concepts. It is unfortunate that they do not weave these ideas back into the essay, but leave the reader to figure out how these ideas then play out given the remaining information they present (in text and image). I was looking forward to their unpacking the ‘affect of experiencing impunity’ and their interpretation of the presented terms, but these ideas are orphaned on the first two pages without a rescue reference in the following eight or so pages.

The authors’ claim to have pushed limits by ‘erasing the border that separates the represented from the representing subjects seemingly unalterable in the documentary mode’ is burdened with assumptions about documentary and/or ethnography that would require another essay to discuss altogether. I encourage the authors to review the literature in visual sociology or visual anthropology (although some of the material is anchored in representation). There are a number of authors who blend text with images that are not burdened with the representation repudiated in this essay.”

Reviewer B: “Impunity is, without a doubt, a serious issue in Mexico, and it is a word that scholars of Mexico will connect with immediately, but it is also a word that has become inextricably linked to human rights activism. This isn’t a bad thing in itself. There is no contradiction between scholarship and activism. However, the authors use the word without examining its meanings or implications as scholarship should. Who has impunity from what? How is the impunity felt by the people in these images? . . . Many of the other words the authors use seemed to be more relevant and can be found in the images: vulnerability, uncertainty, precariousness, even precariat. If the authors believe strongly in the impunity framework, then they should explain more fully what precisely impunity means in this case and how it is connected to the images.

There is also a lot of wordplay surrounding the word affect. The wordplay, in this instance, makes the discussion confusing rather than clarifying. A reader needs contextual clues to tell whether the word means ‘emotional presentation/performance’ or ‘impact,’ and these clues just aren’t there. A discussion of affect (emotional performance) would be very valuable, but that gets lost here. Also, actant seems an awkward word choice. Why not agentive or participatory? I have similar critique of the use of imminent and immanent. The meaning here is obscured rather than clarified by the wordplay.

The authors write that ‘we have sought to push the limits of documentation and representation by erasing the border that separates the represented from the representing subjects seemingly unalterable in the documentary mode.’ This is an important sentence that describes the intention of representing the people of Tulum in the way that the authors have. There is some truth here. I like the connections that these images facilitate as the photographed subjects look directly into the camera and smile. However, the relationship that I am most aware of, as a viewer, is my own relationship to the people pictured, not their relationship with the photographer (the representing subjects). One would assume that this is also the relationship that the authors sought to facilitate by creating these images (recognizing, of course, that it is the photographers or ‘representing subjects’ who facilitate this relationship). The text could be made stronger through incorporating the relationship between the viewer and the images in the argument. Also, visual anthropologists have been attempting to erase and redraw the borders between photographed subjects and photographers, as well as between photographed subjects and viewers for at least a hundred years. This rich history makes it very difficult to argue that these relationships are ‘seemingly unalterable.’ Even so, I have great appreciation for the way that the photographers and writers have redrawn this line through the combination of the images and text presented here. This sentence could simply do a better job of describing the strengths of the work.”

Editors’ suggestions: “(1) In particular, as the reviewers point out, the terms offered in the essay such as affect and impunity, and the title of the article itself, need to be further unpacked and then returned to at some point in the essay. This unpacking might also include situating the terms within broader visual anthropological literature and work. (2) Tightening the overall arc of the theoretical argument, and choosing the key themes and terms that can be most effectively explained will help with the tension that you highlight between photo, text, and photographer/subject/viewer.”

Authors’ response: “Terms such as affect and impunity need to be further elaborated. As Reviewer B points out, impunity invokes the discourses on human rights; however, by impunity, we understand a general condition in Mexico rather than particular instances of abuse that our essay would want to document for the purpose of bringing it to the attention of activists. The title ‘life under impunity’ seeks to underscore the vulnerability of the subjects with whom we spoke and photographed in Tulum. The experience of impunity in Tulum reflects a situation prevalent in the country as a whole. In our final draft, we will return to these concepts in key places in our essay. We would like to add here that the visual and textual components of the photo essay are independent of each other and should stand on their own. By this, we mean that the text does not explain, interpret, or draw ethnographic knowledge from the specific photographs. On the other hand, the photographs do not illustrate the text. From our perspective, text and photographs motivate the reading of each other without drawing explicit connections. This motivation at once situates the sociopolitical context of the photographs and draws out the tension manifest in the subjects smiling in their vulnerability. They know all too well that those in power can get away with forms of violence that they are subjected to in their daily lives.”

Photo Selection

Reviewer A: “I would like to see a defined order for the images as they should appear on the website. Whether the images ‘bookend’ the text or simply mirror it on opposite pages, the photo essay has an inherent linear order because of the direction in which we read English. This isn’t true for an exhibit hung on a wall, which may have an intended order, but viewers do not have to follow it in order to ‘get it.’ Because of this directionality and recognition that it will be ‘read’ from beginning to end, sequencing manifests an intent for visual argumentation. Denial of the order or refusal to provide an order, for whatever reason, abandons the craft and leaves the editing up to someone without the knowledge of the project, which contradicts the expressed intent of the authors in the first place . . . to create an affect—supposedly, in conjunction with the subjects themselves. Obviously, the subjects have trusted the photographer enough to sit/stand for an image, and so there are assumptions on their behalf about how they will be represented. Woven into such a relationship is the belief that they will be represented accurately and respectfully.

My principle reaction to the images is that there are too many of them! This collection should be reduced to 8–10 max.

Various disciplines weigh images and text with different levels of priority: photojournalism prioritizes text (there may only be one image for inches of text), whereas art photography prioritizes image (many images may only contain captions). The argument about text and image in anthropology is that photos usually supplement text and, as images, simply illustrate what the text already states. In this essay, there is very little deliberate conversation between the text and image and I read that the authors expect the viewer to sense or feel something from the image that then resonates with the text, or vice versa.”

Reviewer B: “My only comment about the collection of images is that it might be improved by providing at least one image of ejido farmland. The framing of the images is very tight. This creates images that are packed with details that can be looked at for long periods of time, but it also feels a little claustrophobic. I wanted to look around. Even the images with more depth of field (the rooftop image and the images with a street in the background) feel very closed in. The street is either perpendicular to the frame or not within the focal length of the exposure. The trees in the rooftop image border the houses and don’t allow the viewer to see what is beyond. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing, and may contribute to the overall argument of the essay about people living within severe constraints. However, when coupled with the extensive (and very appropriate) discussion of ejido lands, I found myself wanting to see them.”

Editors’ suggestions: “As for the images, both reviewers indicate an overall concern of the framing and style of the photographs. Reviewer A believes that the photo essay might better be pared down and limited to 8–10 images, while Reviewer B asks for additional images of ejido farmlands that might provide more of a background sensibility of Tulum and the people photographed. While these are seemingly contradictory responses, they actually both refer to what Reviewer A describes as the centering of the images and Reviewer B refers to as the ‘tight framing’ of the photos. In conjunction with a clarification of the overall theoretical aim, perhaps then this stylistic choice may also be made more explicit. Finally, as you clarify and sharpen the theoretical argument, we ask that you consider the necessity of each photo submitted.”

Authors’ response: “As for the images, we welcome Reviewer A’s recommendations about the more compelling photos. At the same time, we are aware that Reviewer B has appreciated other photographs not included in Reviewer A’s selection. We are leaning toward adding three or four photographs to the six that Reviewer A picked out. Overall, we think it is a good idea to keep the number of photographs to a maximum of ten. In planning the final product, we will consider the necessity of each submitted photograph. We gather that this is a reflection that need not be in the text itself but part of our own thinking process of how we want to situate the photographs vis-à-vis the text.”

References

Agee, James, and Walker Evans. 2001. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Originally published in 1939.

Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang. Originally published in 1980.

Benjamin, Walter. 1999. “Little History of Photography.” In Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 2, 1931–1934, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, 508–530. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap. Originally published in 1931.

Benjamin, Walter. 1968. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” In Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, translated by Harry Zohn and edited by Hannah Arendt, 253–64. New York: Schocken Books. Originally published in 1940.

Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Berger, John. 1991. About Looking. New York: Vintage. Originally published in 1980.

Hartog, François. 2012. Régimes d’historicité: Présentisme et experiences de temps. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Serres, Michel. 2008. The Five Senses: A Philosophy of Mingled Bodies. Translated by Margaret Sankey and Peter Cowley. New York: Continuum. Originally published in 1985.

Standing, Guy. 2011. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Stewart, Kathleen. 2007. Ordinary Affects. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Taussig, Michael. 2009. What Color is the Sacred? Chicago: University of Chicago Press.