Anthropology’s Latent Futures

From the Series: Speculative Anthropologies

From the Series: Speculative Anthropologies

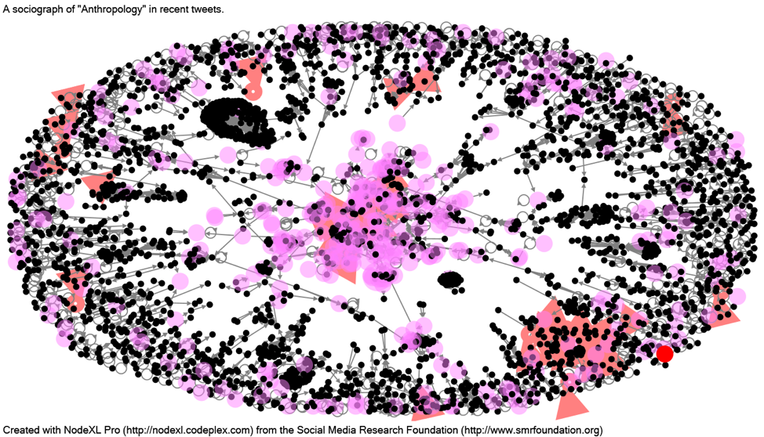

The information visualization below, created in late July, shows 3,300 Twitter users whose tweets contained the word anthropology. Each line (or edge) shows a retweet or a mention, linking users together. The purple circles represent Twitter accounts with the prefix anthro* in their account description; covering anthropological, anthropology, and anthropologist, this term is a proxy for Twitter users who are anthropologists (or represent them). The pinkish triangles represent tweets that contained both the words anthropology and future. The candy-apple circle in the lower right corner is me.

Quite aside from the sense of my own insignificance that this visualization evokes, I hope to direct your attention to the incidence of future talk in anthropology. How frequently do anthropologists discuss the future (however construed)? Could it be, as Taylor Nelms suggests, that for anthropologists as for the citizens described by China Miéville in The City and The City, anthropology and the future coexist in the same spaces without interacting much at all.

To me, though, the sociography above shows the future as a field of latency through which anthropologists move as we engage our research. Wherever we are amid the dots or nodes above, the future is one or two hops away. The future, after all, is latent in all of our pronouncements on relationships, meaning, and action. Describing what is not only makes claims about historical contexts; it also entails prognostications about what will happen and moral desiderata about what ought to be. As Michael Oman-Reagan explains, when we talk to people about their lives or analyze the institutions and practices that (over)determine their oppression, we are simultaneously engaging that future latency. It is a Blochian surplus that haunts the ruins of modernization and globalization that we study.

In Nelms’s “nooks and crannies” of Quito, one might find—however fleetingly—alternatives to capitalist exploitation. In their fieldnotes from The Twilight Zone, Patricia Markert and Jeremy Trombley see uncanny landscapes that “haunt” the modern, “ruptures . . . where tensions refuse to stay beneath the surface of the prescribed ‘normal’.” Along these peripheries and interstices of the real, we are confronted by future alternatives. But dwelling here is not to deny the real nor to invoke long-discarded anthropological solipsism; it is to strive to help the communities in which we work to make the world different than it is today. As Oman-Reagan asks, “What good is an anthropology that doesn’t imagine better lives and futures, and then work to make them real?”

It is in the space of this rupture from the status quo that anthropology discovers SF. Of course, there is nothing inherently emancipatory or critical about SF; historically, it has been less about rupture or alterity than bourgeois reassurance of a continued white, Western, and heteronormative dominance of the world through exploitative capitalism and revanchist colonialism. The genre can just as easily buttress reactionary arguments and project an abyssal neoliberalism into humanity’s far future—Robert Heinlein rather than Octavia Butler.

The SF that anthropology needs is not the extrapolative nor the predictive sort. It is, instead, an SF of hybrids, of excess and of transgression. It is Donna Haraway’s (2016, 1) Chthulucene of speculative fabulation, where the future gives way to creatures “entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings.” As David Colón-Cabrera argues, SF that merely recapitulates the inequalities of the present needs to give way to possibilities that imagine the modern along radically different axes of power and possibility. In Nnedi Okorafor’s Lagoon, for example, aliens introduce radical change, but this change is also a radical return to Nigerian narratives and mythology. In the process, what counts as modern and the future (as a modernist project) is called into deep question.

Yet it’s still worth asking what anthropology can take from these fictions. Certainly, no prescriptive blueprint for the future. Instead, Okorafor’s fictions (along with other Afrofuturist, indigenous, and other non-Western SF) show the exhaustion of the future as a Western trope; they break through a phantasmagoria that was always a bland repetition of the same. This is Walter Benjamin’s flash of lightning, which reveals the utopian impulse amid the ruins of the twentieth century. It is that shock that might move our attention from the pragmatics of the real to the Chthulucene that lies like a seed concealed in the core of anthropological fieldwork. The hopes that our interlocutors conjure, and the gaps between those hopes and the conditions faced by migrants and the marginalized open up the possibility of SF futures in which, as Gilles Deleuze (1991, 31) writes, “differences in degree” (the future as more or less of the present state of affairs) give way to “differences in kind” as becoming or multiplicity.

Does this mean replacing the real with (speculative) fictions? But what is more tragic than reducing “reality to what has become real” (Bloch 1996, 157)? Isn’t it more realistic to attend to our interlocutors’ desires to be free of oppression and exploitation, from what David Valentine calls the “extractive, exploitative systems that got us in this Anthropocene mess”?

When we start down this road, we do so as what Oman-Reagan calls speculative anthropologists, but also as anthropologists of the real, with science fiction as anodyne to the repetitive dreamworlds in which we toil. The real, here, means that we look to moments of rupture, the space of caesura, for clues to a real that we are not allowed to imagine. That real, ultimately, means the demise of one version of the future—the recrudescent military expansion of white colonials into the “galaxy nullius” around us—and its replacement with the concerns of people who seek alternatives to their subjection.

Bloch, Ernst. 1996. The Principle of Hope. 3 volumes. Translate by Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice, and Paul Knight. Originally published in 1955. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1988. Bergsonism. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.