Fieldnotes from the Twilight Zone

From the Series: Speculative Anthropologies

From the Series: Speculative Anthropologies

It is 1959. A city man, suit-clad and impatient, returns to his hometown after a twenty-five-year absence. He arrives to find his eleven-year-old self carving his name into the wood of the park pavilion, everything unchanged, his parents still living in his boyhood home. Stuck in his own past and overwhelmed with nostalgia, the man ends up in an anxiety-ridden confrontation with his younger self on a carousel, resulting in an injury that alters his body in the past and present. As he limps back to his car, a voice announces to you, the viewer, that you have just been a visitor to the Twilight Zone.

Rod Serling, the creator of the television show The Twilight Zone, grew up in Binghamton, New York. He took mid-century TV by storm with his weird, speculative tales that twisted reality just enough to delight and disturb viewers. In early episodes, it’s clear that Serling draws regularly on the familiar—including the landscape of his hometown—to create the weird. The carousel featured in “Walking Distance,” the episode described above, was based on his memories of a carousel that still stands on Binghamton’s West Side. Equally interesting is how the work of Serling’s imagination erupts back into Binghamton’s landscape. A pavilion similar to the one from “Walking Distance” was erected, years later, near the carousel from his childhood. A plaque recognizes this act of imagination-turned-reality. The carousel, which still runs during the summer, has been refitted with panels depicting scenes from the show.

Binghamton is a beautiful place to live, nestled in the New York hills at the confluence of two rivers, especially in the summer and the fall. But it is also a strange landscape, a Rust Belt city that wears evidence of its former glory as a canal town, as the site of prosperous shoe and cigar industries, and as the neighbor to the hometown of IBM. In the hometown of the Twilight Zone, there are many elements of the uncanny that emerge in both landscape and history.

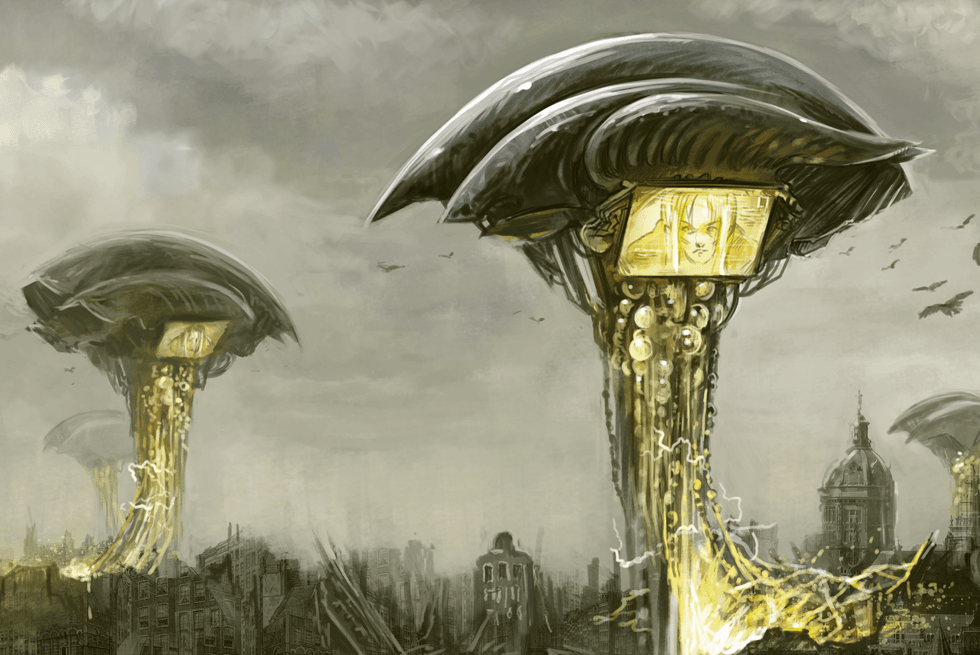

The imposing Gothic Revival–style Inebriate Asylum, which housed those struggling with addiction during the nineteenth century and those suffering from mental illness into the late twentieth century, sits empty on a hill looking out over the town. The Brutalist architecture that characterizes the municipal buildings and the university, once seen as utopian and futuristic (it aged about as well as the optimism of the 1950s), would make an apt setting for a mid-century futurist novel or maybe one by J. G. Ballard. The IBM chemical spill that contaminates parts of nearby Endicott has impacted the health of residents for decades (see Little 2014), an Area X of our own creation. Few signs or monuments mark the violent erasure of Indigenous people (the city and the university, in particular, sit on ancestral Onondaga territory) or the headquarters for the New York State chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, but those histories haunt the landscape as well.

These are references to real moments and buildings in Binghamton. They are far from speculative, although they cause us to speculate. The unsettling moment is the realization that maybe what has seemed familiar has in fact been distorted, haunted, or dangerous the entire time. The question becomes: how does one live in a world that is suddenly unfamiliar, unstable, unsafe?

For many, of course, this uncanny world has always existed. Serling had a particular talent for exposing the cracks in normalcy to reveal the uncanny and thereby to make the familiar strange. In many episodes of The Twilight Zone, he used the show as a platform to explore social and political issues from racism to Cold War paranoia (Spencer 2018). SF has the ability to destabilize illusions of the normal, that which privilege obscures and maintains, and to make audiences reconsider their assumptions in unsettling ways. Speculative writers engage this power all the time; just read Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Helen Oyeyemi’s The Icarus Girl, or Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle, or watch Jordan Peele’s Get Out. (It’s only appropriate that, in the world being built around us today, Peele will be behind the upcoming Twilight Zone reboot).

By skewing the perceived real, speculative fictions like The Twilight Zone draw us into encounters with other realities, often ones that consist of discomforting, hidden, or forgotten stories, engendering a sensitivity to the unusual as it exists in everyday life. Learning to think anthropologically can be said to have a similar effect. We learn to pay attention to details that most people take for granted. We pose questions that disrupt that veneer of the everyday, the normal, by seeking what lies beneath. At times, we may even use speculative techniques to convey ethnographic ideas, as in Anna Tsing’s (2014) homage to Marylin Strathern, subtitled “Testimony of a Spore.” Anthropology is, Tsing (2015, 37) writes, an “art of noticing,” of attending to that which would otherwise go unrecognized. This shared trait of SF and anthropology has, at the very least, the power to open up new ways of looking at a complex world; at most, it has the potential to shape it into something better.

Something as simple as a pavilion in a park demonstrates how The Twilight Zone and Serling’s imagination became material, altering Binghamton’s landscape. As SF authors speculate on the worlds they observe and imagine, they are subtly shaping our material realities, posing critiques and prompting change. Anthropologists, particularly as their arts of noticing become community-centered, collaborative, activist, and engaged, enter the feedback loop as well—from the speculative to the real and back again. We can find inspiration in the words we read as well as the conversations we have with SF writers on parallel journeys.

Together, we enter another dimension, one of sight, sound, and imagination, a dimension of both shadow and substance. Next stop, the Twilight Zone.

Little, Peter C. 2014. Toxic Town: IBM, Pollution, and Industrial Risks. New York: New York University Press.

Spencer, Hugh A. D. 2018. “Social Justice from the Twilight Zone: Rod Serling as Human Rights Activist.” Dialogue 5, no. 1: 1–13.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2014. “Strathern beyond the Human: Testimony of a Spore.” Theory, Culture and Society 31, nos. 2–3: 221–41.

_____. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Postcapitalist Ruins. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.