Monoculture's Troubled Futurities: A review of "A Future Buried in the Past"

From the Series: Sugarcane Heterotopias: Daniel Bustos-Echeverry's film "A Future Buried in the Past"

From the Series: Sugarcane Heterotopias: Daniel Bustos-Echeverry's film "A Future Buried in the Past"

A Future Buried in the Past is a beautiful portrait of the unfulfilled promise of monoculture agrobusiness for rural communities. It is set in the town of Sincerín in the Colombian Caribbean coast, where from 1909 to 1953 the Ingenio Central Colombia, a sugar mill owned by two brothers from a prominent Cartagena family produced sugar for national and international markets. Colombia, like the rest of Latin America, was integrating into the world economy at a fast pace at the turn of the twentieth century through exports of goods in high demand abroad. In the case of Colombia, it was primarily coffee but also bananas, rubber, tobacco, and cattle that facilitated this integration. As exports fueled the national economy, industries bloomed: sugar, flour, and textile industries, among others, incarnated the dreams of progress of the ruling elites, who established protectionist measures around them in the early twentieth century. But, as we now know well, the profits of progress only benefitted a few: the cost was high for local peasants turned into laborers, whose lives and dreams carried little value for the owners of capital.

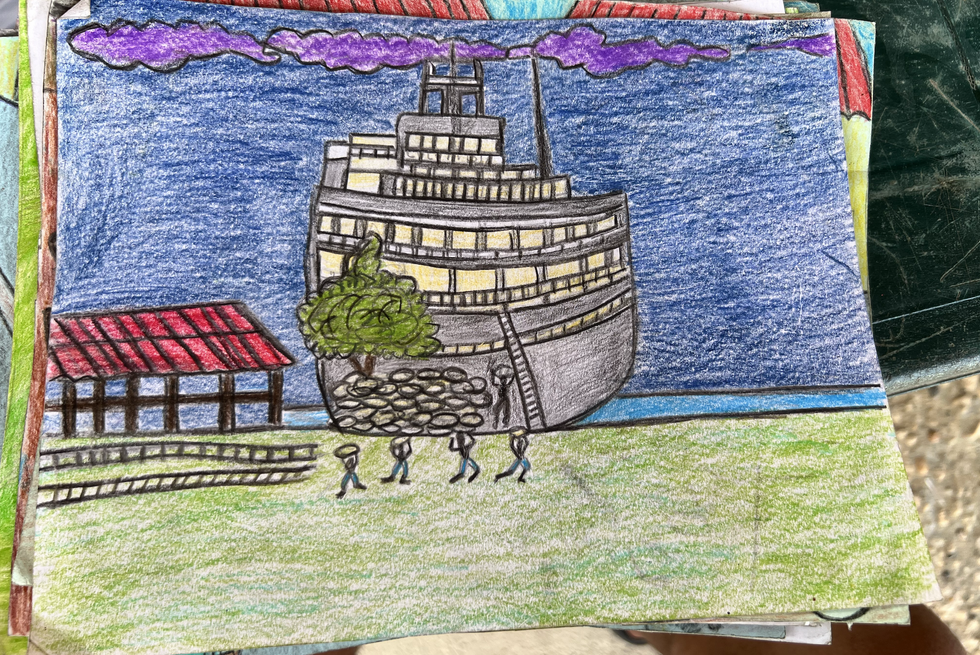

In Sincerín, the brothers Carlos Vélez Daníes and Fernando Vélez Daníes who had built a fortune on cattle exports, sought advice from Cuban engineers and imported machinery from England to establish a sugar plantation and mill. They set up railways to bring the cane to the mill and built a port to load steamboats with the processed sugar (Ripoll de Lemaitre 1997). In this film, Daniel Bustos-Echeverry focuses on the memories of the elders who worked for them and contrasts them with the narratives of the elites. El Porvenir, a newspaper from Cartagena reproduced in the film, portrayed the mill as a success story that had turned lands and peoples that were wild, sleepy, and miserable before, into a paragon of progress. For the elders, in contrast, this is a story of abuse, racist discrimination, policing, loss, and exile. The film opens with an elder recalling that, when workers died, the owners used their bodies to cover potholes in the streets. The Vélez brothers are referred to as all-powerful: “the owners of the lives, the sorrows, the deaths, the names, the lands, the river, the cane, the sugar, and the drinks.” We hear other stories of injustice along the film, like the story of Gregoria Gutiérrez, who as a child longed to join the baseball game that the white Cubans employed by the mill brought and enjoyed, but she was not allowed because the game was only for “the white gods.” In another scene we hear about Diógenes Blanco, who was exiled when “the gods” got angry because he did not appear to be respecting their imposed nightly curfew. And after he left, the money he had been paid for cutting cane had no value elsewhere: workers were paid in the company's currency.

Yet, the direct voices and faces of the elders are barely present in the film. They are instead represented by the local artist César Villa Gutiérrez, who is the main narrator. Villa Gutiérrez was not alive then but undertook interviewing those who were. These memories have inspired him to make a series of vivid paintings that are at the heart of the film, as they become carriers and activators of memory and an ethnographic product in themselves. Through them, he claims to “recuperate and experience the ghost of Ingenio Central Colombia.” In this sense, the paintings are a sort of portal that allows Bustos-Echeverry to generate a juxtaposition between past and present: a past that is not gone, but inhabits the dusty town today, the former port where horses now graze, the baseball field set up by the Cubans, the church where the saints were replaced by statues of San Carlos and Santa Catalina, saints that carry the names of the mill owners, the ruins where weed grows, the abandoned houses, the poverty left behind.

Through Villa Gutiérrez and his paintings, the film provides a threefold critique of existing historical narratives, and in particular, the narrative of those in power as portrayed in El Porvenir. First, it challenges conventional history's use of primary sources. The recollections of the elders and the landscape itself are given precedence as sources, especially as they seem to contradict what the newspapers, so often privileged in historical knowledge, reported. Second, the film unsettles the conventional temporal frame that assumes progress is the expected direction of the passing of time, and that past, present and future are distinct moments. Villa Gutiérrez views his paintings as a “Primitivist Archive” which “speaks to the ruins of a future that never was.” Past and present coexist in a narrative created by Villa Gutiérrez and Bustos-Echeverry around the juxtaposition of paintings that depict the past with the landscape in the present, dominated by ruins and scarcity. Finally, and this is where the film is strongest, the film privileges beauty and aesthetics over explanatory reason as part of its challenge to conventional historical and journalistic narratives. Emotions are stirred through an aesthetic focus on landscape that uses both image and sound. Here, just as the elders, the landscape testifies to the unfulfilled promises. Rather than seeking to illustrate reality, the dusty town of Sincerín, the weeds that creep and brings new life to the ruins of old buildings, the crickets and cicadas that orchestrate some scenes, the pigs and chickens that roam abandoned houses of past splendor, and the old man who pays a visit to the new saints that replaced the old, offer evidence that appeals to the senses and to emotion.

The challenge that the film poses to history is not new. It taps on a now well-established critique of archives as institutions that, far from neutral, are part and parcel of the construction of power relations (Guha 1983; Trouillot 1995; Stoler 2010). It is also reminiscent of Hartman's invitation to push disciplinary limits by exposing the violence that conventional forms of knowledge generate, not only by erasing the experience of certain subjects but also by privileging data and explanatory reasoning (2007 and 2008).

While the importance of highlighting the “other side” of the history of Sincerín's sugar mill is unquestionable, there are ways in which the perspective could be further complicated. The filmmaker choses a dichotomic entry into the story, pitching the elders' narratives that apparently live only in memory and orality with the seemingly hegemonic ones recorded in newspapers and the archive. While there is no denying that most archives have been produced to serve the interests of those in power, it is also true that historically, indigenous peoples, afro-descendants, women and workers, among other groups, have also used archives and writing to advance their agendas. Since the colonial period they have done it to negotiate their own interests, speaking the language of a power they couldn't deny, but also as a tool to solve internal matters. During the first half of the twentieth century, the time during which Ingenio Central Colombia was active, examples abound among agricultural and factory workers all over Colombia (LeGrand 1986; Archila Neira 1991; Palacios 2011). The fact that in the film, the voices of the workers appear almost mythical, and their histories seem to happen in a different dimension from that of the owners, could reinforce the presumed ahistoricity of the workers already present in the newspapers of the early twentieth century.

Watching the film, I found myself asking whether these mill workers also challenged the model of modernity imposed by the owners and the ruling elites. In what ways did they engage with and respond to it back then? In the film, it is left to Villa González to play this role. He paints against erasure, and thus creatively reclaims the right to record, to tell, to archive, and ultimately, he reclaims his community's right to make history.

Archila Neira, Mauricio. 1991. Cultura e identidad obrera: Colombia 1910–1945. Bogotá: CLASCO.

Guha, Ranajit. 1983. “The Prose of Counter-Insurgency.” In Subaltern Studies II, edited by Ranajit Guha, 1–42. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Hartman, Saidiya. 2007. Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

———. 2008. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2: 1–14.

LeGrand, Catherine. 1986. Frontier Expansion and Peasant Protest in Colombia, 1850-1936. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Palacios, Marco. 2011. ¿De quién es la tierra? Propiedad, politización y protesta campesina en la década de 1930. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes.

Ripoll de Lemaitre, Maria Teresa. 1997. “El Central Colombia. Inicios de industrialización en el Caribe colombiano.” Boletín Cultural y Bibliográfico 34, no. 45: 59–92.

Stoler, Ann Laura. 2010. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press.