Our Electric Air

From the Series: Our Lives with Electric Things

From the Series: Our Lives with Electric Things

Conjure an electric fan in your mind’s eye. Set it on your desk, and plug it into the nearest socket. An electromagnetic field loops around the stator, the rotor twists, the blades curve, and voila—current to currents. A windmill in reverse.

Once the power is on, fans spin air into improbable forms: the mammoth blast of a wind tunnel, or the plush breeze cascading down from the ceilings of my Florida childhood. Whatever the pattern, it is steady, constant, repeating. Order and change manifest in the continual rotating whirl.

The last century has seen an explosion of fans (a fanthropocene?). The old GE models were quite beautiful, ornate metal flowers suspended in lattice globes. Today, their descendants are sleeker and cheaper and stronger. They are nestled throughout our technosphere, cooling everything from engines to computers. Parasitically, they sit at the heart of another system, redistributing its forces and flows. But as Michel Serres (2007) reminds us, parasites are useful and even necessary; their redistributions are what allow systems to keep going.

Dar es Salaam, where I conduct fieldwork, is a city with little ventilation. People long to move to the periurban outskirts where there is mpepo, wind. Rich bureaucrats and white aid workers retire to air-conditioned enclaves, but almost everyone else can still afford a cheap fan. In the cramped rooms of poor Swahili neighborhoods, fans create spaces to rest and cool down—to pumzika, breath—in anticipation of the next day. They are small, democratic breeze machines, redistributing the air—as long as the power supply holds.

ON AIR. Border police of the sacred. Do Not Enter. The air is sucked out to create a pure location for transmission. ON AIR.

Inside: Soundproof walls. Acoustic foam. A chair on wheels. A hanging mike. A script. A playlist. A job to do. A boundary to protect, create, transgress. ON AIR.

Gray and silver metal. Where is the earth, wind, sky, birds calling, an airplane, and the soft chatter of children playing as this place is ON AIR? No air when on air. There must be a palindrome here somewhere. ON AIRIA NO. Splice the audio with an Italian riff, shout out to my boy Marconi (Raboy 2016). Let’s read this one-way communication two ways. In both directions. Grazie mille e tanti auguri. The 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics. Twenty-two years later on the Mediterranean Sea. Testing to see if your microwave signals could reach that Sestri Levante hill where my nephew tends to the peacocks. Where my cousin runs a restaurant. Where his daughters grow and appear in stunning photos under trellises on granite-paved garden walkways in my Facebook newsfeed. With their mother, who is an ex–runway model from Milan. Via Venezuela. Thank you, Marconi, for slaying that pathway. To and from the sea in the middle of the land. All through open air.

From the estate on the promontory then owned by the industrialist Gualino, rubbing elbows with other elite merchants, bankers, and wealthy Genovese financiers whose families profited from the sea trade long before the bloodied and gleaming pathways that were forged by native son Cristofo Colombo. Pathways to pathways. Waves upon waves. The sound of water lapping against the side of your laboratory yacht Elettra. Wind. Birds calling. Modulated waves harnessed. Controlled fluidity. Protected by border police. Shout out to Hermes, god of transitions and boundaries. Hermetically sealed. No air when on air. Regulated by which force? Pure signal.

What kind of purity? With what cost and consequence? Border police of the sacred. The red sign outside the studio door is ON.

In Delhi, the spinning wheels of growth grind into the ground, throwing up smoke and dust. Construction BOOMS—the sound of the city’s growing pains. As developments rise, air quality falls. In this risky society, purity and danger are redefined. Delhi’s air is now understood to be freighted with matter out of place. Breathing has become a problem. Everyone suffers; as Ulrich Beck (1992, 36) once argued, “smog is democratic.” At least, it used to be. Air purification machines, now available in the city’s home appliance markets, promise to scrub airborne particles from the homes of people who can afford them.

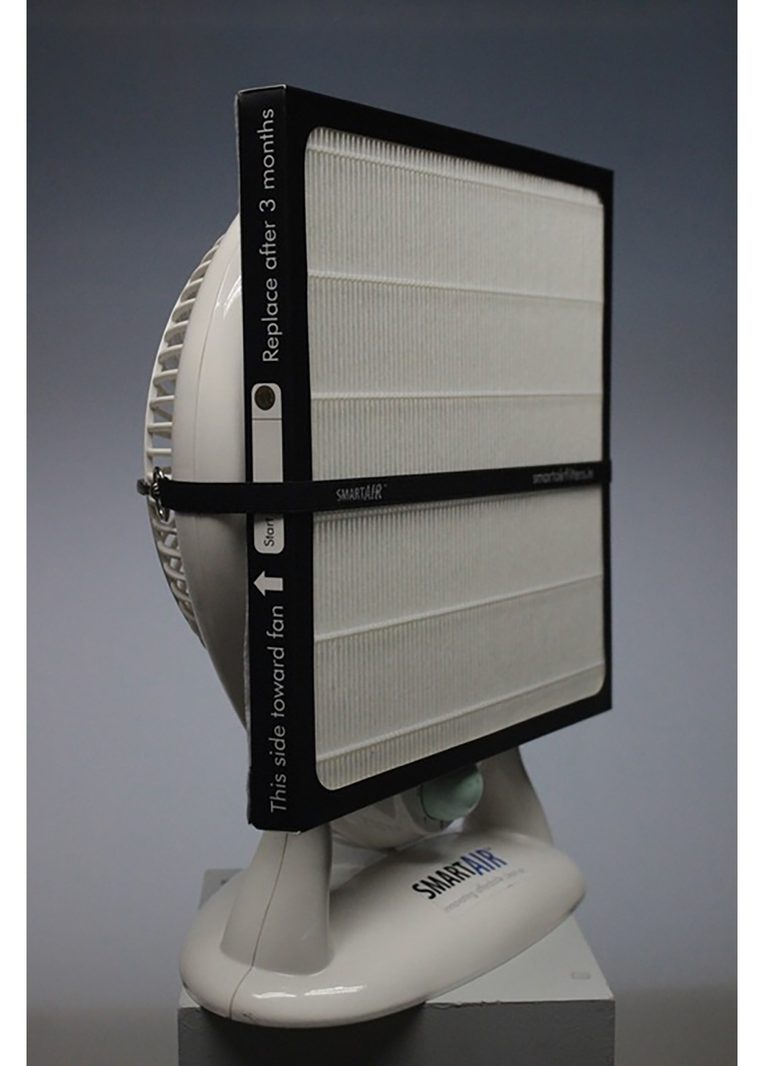

Middle-class homes in Delhi already feature mediating machines at the openings where pipes and wires enter. The water purifier and the backup power inverter have been present for years. The air purifier dovetails with existing market logic: the need for households to make their own breathable air presents an economic opportunity. Smooth, white, big-brand purification machines are pricey, but, marketed through appeals to scientific rationality and care for one’s family, they seem an urgent necessity for those with the money. Promotional graphs of decreasing household particulate levels are positioned next to images of children and elderly relatives breathing easier.

By exposing the essential components of higher-end purifiers, the social entrepreneurs behind this simple machine—a HEPA filter strapped to a Chinese-made fan—promise cleaner air to a lower-cost market. Could this foreshadow the emergence of homemade purifiers assembled from locally available materials? Not quite yet. The fan is cheap, but the filters still are not. Perhaps public action against pollution will make these devices unnecessary. Until then, those without the means to privately purify their air must continue to inhale the sediments of India’s development.

Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Translated by Mark Ritter. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage. Originally published in 1986.

Raboy, Marc. 2016. Marconi: The Man Who Networked the World. New York: Oxford University Press.

Serres, Michel. 2007. The Parasite. Translated by Lawrence R. Schehr. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Originally published in 1980.