Last winter, Cultural Anthropology and the Visual and New Media Review had the opportunity to screen Collecting in the Collection: 46 Inuit Artifacts in the Berlin Ethnological Museum from Franz Boas's 1883–1884 Baffin Island Expedition, by artists Rebecca Sakoun and Florian Göttke. That film addressed anthropological and artistic themes ranging from tactile ways of knowing to the status of the encounter on postcolonial terrains. One year later, we have the pleasure of screening Griot, by Daniel Lema, and there are striking overlaps between the two films.

Synopsis

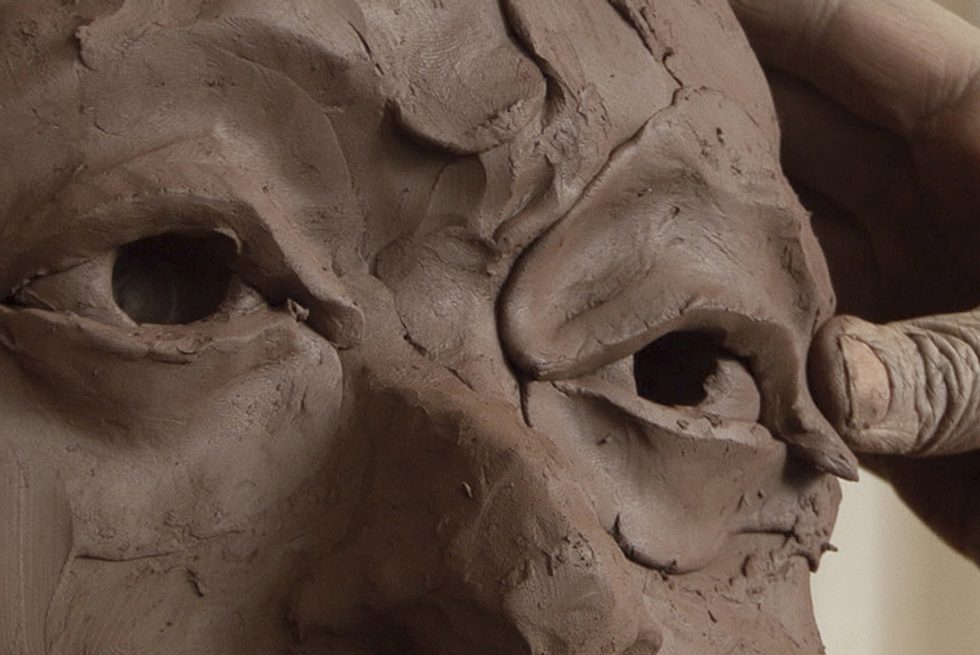

Griot is a thirty-minute documentary, filmed in 2014 by Daniel Lema and produced as part of the Granada Centre for Visual Anthropology at the University of Manchester. The film explores the work of Kevin Dalton-Johnson, an international artist who deals with issues of memory and identity through clay. Lema’s ethnographic film is mostly observational and stands out because of its emphasis on forms of nonverbal communication and exploration.

Biography

Born in 1985, Daniel Lema completed a degree in law and economics before going on to study photography in Edinburgh. There, his work was exhibited at the University of Edinburgh. He then pursued an Masters in visual anthropology at the University of Manchester. Since then, he has deepened his interest in ethics, aesthetics, and storytelling, and his films have been shown at various ethnographic film festivals in Europe. He is currently working as a videomaker and lecturer in Spain, while conceiving a dissertation project about how water weaves daily life, memories, and expectations in one of the largest irrigation areas of Western Europe, the Spanish natural desert Los Monegros.

Interview

Sander Holsgens: How did the idea for Griot come about? And how did you establish a relationship with Kevin Dalton-Johnson?

Daniel Lema: Kevin and I had met for a photo shoot in his studio some months before filming the documentary. I did not really know who I was going to photograph; we had met during a concert in Manchester, so this was a chance to get to know him better. When I saw him at the concert, he was well-dressed and his long dreadlocks were wrapped in an elegant tam or rastacap. The dreadlocks and the outfit did not match the stereotype I had in my mind about Rastafarians, so I asked him if he would like to have a portrait taken. What I discovered was an amazing artist driven by an amazing life story. The photo shoot was good, but I had the feeling that some elements of Kevin’s story could not be told with photographs, or at least not in the way that I wanted.

During that period, I was exploring the narrative potential of moving images and sound through the visual anthropology program at the Granada Centre. One of my lecturers was the visual anthropologist Michaela Schäuble, who encouraged me and my colleagues to explore the medium in any way we wanted. Meanwhile, you [Sander] and I were engaged in a set of interesting conversations about Robert Gardner’s (1986) Forest of Bliss. Months after my shoot with Kevin, I proposed the idea of making a film about his artistic process by documenting the production of one of his clay busts. Kevin was kind enough to accept.

SH: According to the blurb of the film, griots are West African historians or storytellers: repositories of oral tradition. Could you tell us more about this? If Kevin’s sculptures can be considered griots, then what is their story?

DL: In West Africa, griots are storytellers, poets, singers, historians and advisors who transmit stories, often about communities or families, through music. The term griot comes from the French guiriot, which is a transliteration of the Portuguese word criado (servant). Local terms can take multiple forms, however. For instance, in the Northern Mande culture, griots are referred to as jeli; guewel in the Wolof areas of Senegal; gawlo in Pulaar by the Fula people. One of the most extended terms is jeli, which comes from the root djali or jali, meaning blood. Traditionally, griots, males and females, are an endogamous cast that could hereditarily transmit the jeliya (or musicianhood) as inherent blood knowledge. Each family has a griot upon whom they could rely and who would be invited for all special occasions, such as weddings and funerals.

Regarding the sculptures that Kevin creates, griots are related to personal life events and memories. His sculptures represent important persons in his life, for the good and for the bad, and thus the clay is utterly charged with his emotions and memories. In Kevin’s own words, his journey is about the existential necessity of expressing his concerns about his diasporic identity. He has a strong personal life story, and I would invite anyone interested in engaging it at length to visit his website.

SH: It seems to me that you’ve embraced some particular filmic aspects of observational cinema, such as the long take and the exclusion of both a voiceover and interviews. Why did you choose this approach to filmmaking?

DL: The way things are experienced and perceived by subject and filmmaker offers, of course, a great variety of aesthetic possibilities. I think that the sensitivity of the filmmaker has to allow for the specific features of each subject to impose the cinematic approach, and thus a form of aesthetics. For instance, the film Ethnofiction, by Johannes Sjöberg (2007), develops a very sympathetic approach to “being transsexual” in São Paulo by reenacting the everyday life and memories of two transsexual individuals. In addition to empowering the subjects by allowing them to decide how they wanted be represented, this approach also gave access to aspects of their lives that otherwise might not have been reached. Sjöberg’s collaborative approach thus contributed not only to the aesthetics of the film, but to a deeper comprehension of the subjects by the spectator. Being attentive to both subject and environment allows the filmmaker to recognize different aesthetics and then leave them to consolidate in one way or another. For me, this sensitivity as a state of mind should be sustained throughout the filmmaking process, from planning to editing.

In the case of Griot, the use of the spoken word was not an option if I wanted to focus on the relationship between Kevin and the clay, and both of them in relation to his workplace. As Kevin’s experience of working with clay could not really be comprehended by talking about it, I felt that the film should leave room for the less intelligible aspects of this relationship, such as emotions, body language, working rhythms, and temporalities within his artistic process. In deciding to use this nonexplicit approach, I admit that Forest of Bliss was a key influence. Its rhythmic use of sound and image left a profound impression on me. Instead of defining in order to comprehend, the film was an invitation to feel and sense a particular place in order to understand.

The notion of place was important for me in the way that I understood Forest of Bliss. In the same way that the richness of textures and forms of an actual place may favor specific ways of perceiving and experiencing it, the structural complexity and textural richness of Forest of Bliss makes it a place of its own. For me, it is a film with almost endless places. If David MacDougall (1998, 11) contends that film is a form of “commensal engagement with the world” that “favours experience over explanation,” then Forest of Bliss strikes me as one of the best audiovisual examples of this. So it is this way of thinking about place that I wanted to achieve with my filmic approach: as a nonverbal exploration of a relationship conceived as a multidimensional place where body, memories, and artistic objects experience and influence each other at their own pace, under their own temporalities.

SH: Griot seems to me to be the exploration of cinematic rhythm. Not only is there the rhythm of editing, camera movements, and soundtrack, but also of texture, lighting, color, and movements of the body. Rhythm, you seem to argue, is in work, but also in daily activities and in people’s interactions with each other and with things. How did the notion of rhythm inform your approach to filmmaking?

DL: Daily rhythms seem to go unnoticed in most filmic representations, mostly, I guess, due to the widespread popularity of character-based narratives and grand stories. These grand stories tend to overlook aspects of human experience, such as the everyday. Yet it is in the small, often unnoticed interactions between our bodies and the world that we encounter our essential relationship to places and our environment. In the case of Griot, once the images and sounds of Kevin’s artistic process are presented in a manner that allows viewers to hold their gaze and tune their ears, all of those textures, sounds, bodily actions, and objects intermingle in a tangle where rhythm appears as an interweaving force.

On the other hand, I think filmic rhythm can be understood as a narrative substitute for the characters of conventional stories, precisely because it is able to interweave experience with film in a way that resembles how we live our lives. Such is the case in Forest of Bliss or in Leviathan, by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel (2012), where conventional characters have been decentered in order to approach life experiences from a sensory and bodily perspective. I think rhythm, in this approach, is the weaving force at the base of filmic narrative. Dziga Vertov's (1929) Man with a Movie Camera is another great example of a cinematic rhythm that is based on everyday rhythms at the level of people's interactions with the world.

A filmic rhythm does not need to be a conventional harmonic rhythm. In Griot there is, for instance, a set of close-up shots of the clay pieces being emptied, which lasts around fifteen minutes. It finishes with a wide-angle shot showing the discarded clay, a culmination of the emptying process. Across these sequences and within each sequence, repetition apparently shows a variety of rhythmic and less rhythmic interactions. In the case of this series of shots, though, the aim was to expose emotional interactions between clay, place, and artist, in order to think about this emptying ritual as a cathartic process. Meanings, in this view, are not so much a self-contained compartment but that which arises through rhythm as viewers deal with shifting points of view and repetition. Or to paraphrase David MacDougall (1998): what I looked for in this film was a form of knowledge by acquaintance, rather than knowledge by description.

Cinematically, it is interesting to consider how meanings and audiovisual arguments are conveyed through aesthetics, which are partially an obvious consequence of editing. Through editing it seems that long takes are able to produce a kind of suspended time, which amplifies tension instead of simply conveying a long lapse of time. On the other hand, it is through cuts and repetition where time—paradoxically, perhaps—can be extended or stretched and rhythm can become most meaningful. In the case of Griot, the viewer may be able to grasp a kind of bodily and sensorial understanding through repetition in the shots, but also through the pace of Kevin’s gestures and thus his emotional condition, through the textures that skin and the process of sculpting creates on the clay. It seems to me that whereas rhythms of life are a kind of tissue that is interwoven with (and interweaves) the experience of life, rhythms of cinema produce a similar effect at the level of narration and aesthetics.

References

Castaing-Taylor, Lucien, and Véréna Paravel. 2012. Leviathan. 87 min.

Gardner, Robert. 1986. Forest of Bliss. 90 min.

MacDougall, David. 1998. Transcultural Cinema. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Sjöberg, Johannes. 1997. Ethnofiction. 27 min.

Vertov, Dziga. 1929. Man with a Movie Camera. 68 min.