Ethnographic fieldwork is increasingly becoming (and perhaps has always been) a space of multimodal experimentation. As a number of recent interventions have made apparent (Collins, Durington, and Gill 2017; Dattatreyan and Marrero-Guillamón 2019; Westmoreland 2022), the anthropological engagement with more-than-textual media, such as games, graphic novels, interactive documentaries, performance experiments, ethnographic podcasts, and many more, doesn’t respond only to questions of ethnographic representation, but it crucially entails new ways of constituting and inventing the field (Criado and Estalella 2023). Notably, the concept of the “fieldwork device” (Estalella and Criado 2018, 21), understood as an artefact or arrangement that assembles the field in a specifically patterned way, highlights the foundational role of the artefactual or the artificial in ethnography.

The proliferation of fieldwork devices and multimodal media has led many anthropologists to revisit foundational disciplinary questions. These include examining the politics and poetics of ethnographic analysis through multimodal artefacts (Ballestero 2021), reconsidering the forms and norms of ethnographic collaboration (Estalella and Criado 2018), exploring how fieldwork is transformed when mediated by field devices or directed towards multimodal productions (Collins et al. 2017), and establishing criteria for evaluating the anthropological value of multimodal artefacts (Criado, Farías, and Schroeder 2022).

Yet one crucial aspect that has received limited attention in current conversations about multimodality is the fact that multimodality draws anthropologists to an unexpected yet crucial site: the studio. In anthropology, the studio has been primarily imagined as a pedagogical space (Marcus and Rabinow 2008); a space where anthropologists working on partially connected (but individual) projects can be part of a collective, inventive, and processual review process based on the tinkering with materials and concepts. More recently, Cantarella, Marcus, and Hegel (2019) have argued that to the extent that the field is a “found imaginary” relying on forms of controlled speculation and conjectures about what is true and valuable, the design studio is an important site to learn and practice the anthropological craft of imagination and future-making. But in many multimodal projects, studios are more than a pedagogical space. They are key sites where field devices and multimodal artefacts take shape and come into being. This distinction poses important questions: Which forms of collaborations do studios require? What is the relationship between the studio and the field? What are the implications of recognizing the studio as a vital site for anthropological knowledge production? Finally, what might the contours, promises, and ramifications of a “studio anthropology” look like?

The term “studio” emerged in the renaissance to designate small and secluded spaces dedicated to study, reading, and writing. In the eighteenth and nineteenth century, its meaning evolved to describe spaces of artistic creation (Alpers 1998), distinguished from artisans' workshops by the absence of functional utility in the cultural artifacts that were produced (Sennett 2008). Studios emerged as sites for aesthetic and symbolic experimentation. Similar to a scientific laboratory, the studio represents an enclosed space, a site of retreat where practitioners isolate and manipulate elements of the world, assemble them as cultural artifacts which are then reintroduced to the world—exhibited, sold, or otherwise disseminated (Farías and Wilkie 2016). The studio, it seems, stands in stark contrast to fieldwork's emphasis on immersion, collaboration, and correspondence. And, yet, anthropologists are increasingly entering studios to engage in multimodal projects or even establishing anthropological studios (and labs) within academic institutions.

So why are anthropologists turning to studios? One answer could be that the studio fulfills a somewhat similar function to the offices where ethnographic writing occurs, that is, as spaces in which a ‘second field’ is brought into being by the “imaginative re-creation of some of the effects of fieldwork itself” (Strathern 1999, 1). This answer holds merit, as many multimodal works indeed aim to re-enact field sites, experiences, and relationships. However, based on my own incursions into studio practices, I think it is crucial to understand the studio as a space for prototyping the field. Within the studio, researchers create artifacts designed to actively transform both the field and their relationship to it. Studio anthropology, in this sense, advocates an experimental approach to fieldwork, centered on the development of field devices and multimodal artifacts.

To illustrate this perspective, I draw upon two multimodal projects in which I have been involved. These projects exemplify two distinct ways in which an anthropological studio practice prototypes the field through processes I refer to as “idiotic estrangements” and “abductive projections.” I will elaborate on each by recounting the creation of a field device and a multimodal artifact.

The Zauderbude: Designing a Scenography for Idiotic Estrangements

The Zauderbude—literally a “booth for dithering”— was the key field device we created in a research project investigating conflicts and equivocations within a collaboration between public administration officials and urban activists in Berlin (Farías, Marlow, and Wall 2024). We focused on two so-called “Model Projects of Cooperative Urban Development Oriented to the Common Good”: the Haus der Statistik and the Rathausblock Kreuzberg. These two building complexes are undergoing all-encompassing urban renewal processes, in which civil society organizations co-manage the projects alongside public administration. Additionally, these teams coordinate temporary cultural uses during the redevelopment phase. Of particular note is the Haus der Statistik, which has become one of Berlin's most vibrant cultural hubs, hosting numerous discussions and experiments centered on envisioning the city's future.

Developing relationships with the protagonists of these highly political projects was rather easy. My two research collaborators, architect-anthropologist Felix Marlow and architect-urban designer Rebecca Wall, have long been deeply involved in the civic society organizations involved in these model projects. Based on their intimate knowledge of the ‘model projects,’ we conceived our ethnography as primarily aimed to set up knowledge infrastructures—spaces for documentation, discussion, and reflection—tailored to the needs of these civic initiatives. Felix and Rebecca’s office in our anthropology department became the key site—something akin to a studio—for designing and developing field devices, including zines and exhibitions.

The key field device was the Zauderbude, which we conceived as facilitating a scenography for ethnographic estrangement (Cantarella, Hegel, and Marcus 2020). Our aim was not to bring us closer to the field but rather to establish a heterotopic timespace; a space that disrupts and reframes the ordinary, that makes the familiar strange, and thus enables “idiotic conversations,” slowing down thinking and action, as Isabelle Stengers (2005) would put it regarding “the idiot” as a political figure. The challenge, then, was how to make space for dithering and murmuring about what otherwise remains unspoken or unthought.

The design process led us to collaborate with a scenographer to create an interior that exuded an eerie, surreal atmosphere. The space, structured by the dimensions of our small construction trailer parked outside the Haus der Statisktik, was deliberately designed to be disorienting, filled with peculiar objects and unsettling sounds: an embalmed pheasant served as a silent “witness,” the grating noise of an old modem echoed in the background, and other disconcerting elements added to the overall sense of strangeness. The goal was to make the familiar strange, fostering conditions for idiotic conversations—dialogues where hesitation, irresolution, and dithering could emerge and reveal something about the conflicts and equivocations in these model projects.

However, we soon realized that our presence in the Zauderbude would undermine its intended effect. As researchers who had already engaged extensively with our interlocutors—discussing our project’s goals, insights, and arguments—our familiarity risked neutralizing the scenographic estrangement we sought to achieve. To address this, we designed a choreography or protocol for dithering that excluded us, the ethnographers, from the interactions. Instead, we invited interlocutors in pairs, selecting key actors who we knew had much to discuss but rarely found the time. Upon their arrival, an actress, serving as a host, greeted them, apologized for our absence, and facilitated their stay in the Zauderbude. These sessions often lasted hours, while Felix and Rebecca would wait at a nearby café, returning later to debrief and tend to practical matters.

This intentional “idiotic estrangement”—our absence at pivotal moments of the research—was itself a prototype of alternative ethnographic encounters. By transforming field devices like the Zauderbude into infrastructures for open, strange, and idiotic conversations, we contributed to the ongoing process of “infrastructuring” the field. This approach enabled public officials and urban activists to engage in dialogues that might otherwise have remained unspoken, advancing our experimental ethnographic aims.

The Only Game in Town

The second story is based on a year-long ethnography course entitled The Only Game in Town? Anthropology of Housing and Real-Estate Markets in Berlin, which Tomás Criado and I co-taught in 2018–2019 (Farías and Criado 2023). The course invited students to ethnographically explore the calculative and technopolitical practices shaping these markets. Student projects examined these practices within the moral economies of real estate agents, city-owned building companies, and housing cooperatives, as well as the social life of policy and legal instruments. Toward the end of the course, we organized a three-day workshop to prototype games based on students’ ethnographic insights. The workshop was held at Haus der Statistik, one of the field sites previously discussed.

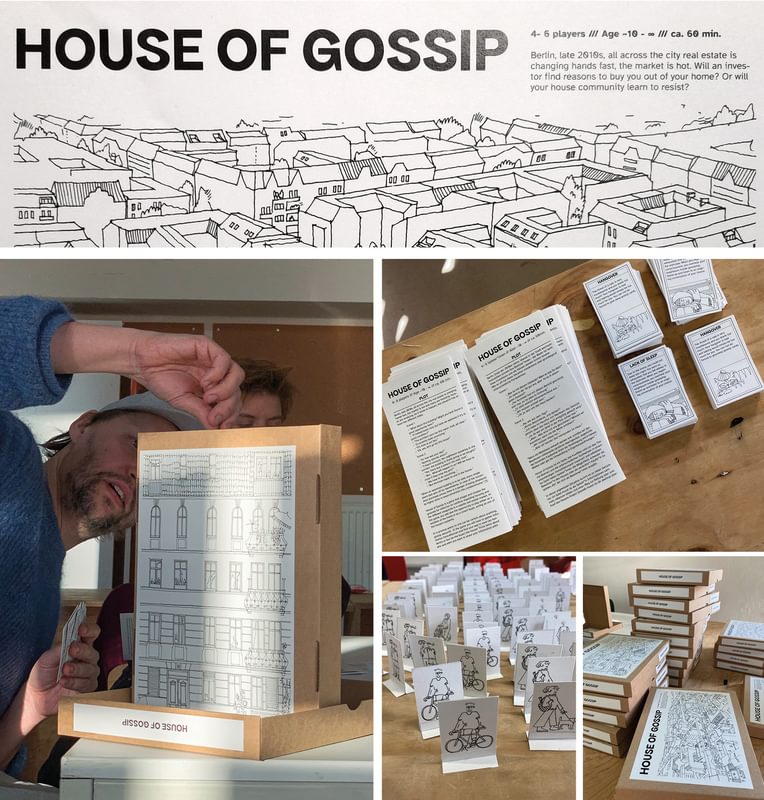

One prototype game, House of Gossip, is set in a staircase—a liminal space where neighbors interact, gossip, and form alliances. Interestingly, staircases were not key field sites in any of the student research projects. The inspiration for this game emerged during brainstorming about a student project on homelessness. Students reflected on how intriguing it would have been to have explored the interfaces between homelessness and conventional housing—a particularly contentious issue in winter when homeless individuals often sleep in the staircases of residential buildings, sparking conflicts and negotiations. Building on this idea, House of Gossip explores the intricate social dynamics that unfold in the staircases of buildings under real estate pressure.

Game design, as undertaken in this context, became an exercise in “ethnographic projection” (Farías and Criado 2023). This practice involves prototyping field sites not yet encountered—an abductive exercise that entails jumping sideways from well-known to partially known field sites. While ethnographic projection occurs whenever we begin imagining a field site and formulating research questions, in this instance, it emerged as a studio practice mediated through game design.

Ethnographic projection extends beyond imagining field sites; it also entails the projection of social figures. This was evident in Sue Them All, another game we prototyped, which revealed tensions between ethnographic and playful figurations. In the game, players assume the role of an activist collective that helps tenants sue landlords by connecting them with supporters, such as lawyers, witnesses, experts, journalists, and friends. Designing the game required us to describe tenants, the conditions in which they lived, and the ways landlords exploited them. However, this led to a critical reflection on game figurations and an effort to create ambivalent player identities resembling those encountered in the field. Hence, the game team began to question their initial focus on cooperative play and altruistic action as core mechanics, considering one of the field’s key challenges: the activists’ struggle to sustain themselves financially. This shift transformed the ethnographic projection. The game evolved to address not only cooperative dynamics but also the pursuit of individual economic retribution for facilitating legal action, adding complexity to its social and economic narrative.

Rather than merely re-describing the field, the games facilitated the speculative projection of field sites and social figures, enabling new forms of engagement with ethnographic material. This approach underscores the role of abductive reasoning, where creative experimentation bridges the known and the partially known. Furthermore, it highlights the generative tensions between a field and a studio research practice. By retreating to spaces for imaginative prototyping, studio anthropology contributes to reconfiguring the field itself, creating devices for alternative forms of social analysis and interaction.

Studio Anthropology

In concluding, I highlight several implications for studio anthropology:

First, studio anthropology does not necessarily unfold in a physical studio. Instead, the term highlights the diverse spaces where anthropologists engage in creating field devices and multimodal artifacts. These are not spaces for recursive conceptual work aimed at re-describing the field; rather, they are spaces dedicated to producing artifacts that modify our relationship with the field.

Second, the anthropological studio differs significantly from the design studio as a “center of synthesis” (Wilkie and Michael 2015), where radically different requirements and constraints are synthesized into a singular material form. In contrast, the anthropological studio produces prosthetic rather than synthetic artifacts—devices that equip ethnographers to navigate and engage with the field. The artifacts crafted in these spaces serve as prototypes of fields and field relations, shaping how the field is understood and experienced.

Third, studio anthropology redefines collaboration within the discipline. While studio collaboration may sometimes involve media-savvy interlocutors (Collins, Durington, and Gill 2017), it often relies on partnerships with cultural workers and technology developers to create fieldwork devices and multimodal works. These collaborations are not primarily para-ethnographic relationships. Instead, they focus on crafting fieldwork devices, shaping their aesthetic and technical affordances, and thereby influencing how a field is constituted.

Finally, studio anthropology embraces the artificial by positioning anthropology as an artefactual practice. It invites a reimagining of the discipline as a “science of the artificial,” with a focus on the social life of ethnographic artifacts and their impact on knowledge production and field constitution. Whether through “idiotic estrangements” or “abductive projections,” the emphasis is on how these artifacts transform our conceptualizations and engagements with the field.

Note

This is an adapted version of my presentation during the plenary session “Doing and Undoing Anthropology” held on July 24, 2024, at the biennial conference of the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) in Barcelona. This research has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101002726).

References

Alpers, Svetlana. 1998. “The Studio, the Laboratory, and the Vexations of Art.” In Picturing Science, Producing Art, edited by Caroline A. Jones and Peter Galison, 401–17. New York: Routledge.

Ballestero, Andrea, ed. 2021. Experimenting with Ethnography: A Companion to Analysis. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Cantarella, Luke, Christine Hegel, and George E. Marcus. 2020. Ethnography by Design: Scenographic Experiments in Fieldwork. New York: Routledge.

Collins, Samuel Gerald, Joseph Dumit, Matthew Durington, Edward González-Tennant, Krista Harper, Marc Lorenc, Nick Mizer, and Anastasia Salter. 2017. Gaming Anthropology: A Sourcebook from #Anthropologycon. AnthropologyCon.

Collins, Samuel Gerald, Matthew Durington, and Harjant Gill. 2017. “Multimodality: An Invitation.” American Anthropologist 119, no. 1: 142–46.

Criado, Tomás Sánchez, and Adolfo Estalella, eds. 2023. An Ethnographic Inventory: Field Devices for Anthropological Inquiry. New York: Routledge.

Criado, Tomás Sánchez, Ignacio Farías, and Julia Schroeder. 2022. “Multimodal Values: The Challenge of Institutionalizing and Evaluating More-than-Textual Ethnography.” entanglements 5, no. 1/2: 94–107.

Dattatreyan, Ethiraj Gabriel, and Isaac Marrero-Guillamón. 2019. “Introduction: Multimodal Anthropology and the Politics of Invention.” American Anthropologist 121, no. 1: 220–28.

Estalella, Adolfo, and Tomás Sánchez Criado, eds. 2018. Experimental Collaborations: Ethnography through Fieldwork Devices. New York: Berghahn Books.

Farías, Ignacio, and Tomás Sánchez Criado. 2023. “How to Game Ethnography.” In An Ethnographic Inventory. Field Devices for Anthropological Inquiry, edited by Tomás Sánchez Criado and Adolfo Estalella, 102–19. New York: Routledge.

Farías, Ignacio, Felix Marlow, and Rebecca Wall. 2024. Zaudern ums Gemeinwohl: Produktive Missverständnisse in der kooperativen Stadtentwicklung [Dithering Around the Common Good: Productive Misunderstandings in Cooperative Urban Development]. Hamburg: adocs.

Farías, Ignacio, and Alex Wilkie, eds. 2016. Studio Studies: Operations, Topologies & Displacements. London: Routledge.

Rabinow, Paul, George E. Marcus, James D. Faubion, and Tobias Rees. 2008. Designs for an Anthropology of the Contemporary. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Sennett, Richard. 2008. The Craftsman. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Stengers, Isabelle. 2005. “A Cosmopolitical Proposal.” In Making Things Public : Atmospheres of Democracy, edited by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, 994–1003. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Strathern, Marilyn. 1999. Property, Substance, and Effect: Anthropological Essays on Persons and Things. London: Athlone Press.

Westmoreland, Mark R. 2022. “Multimodality: Reshaping Anthropology.” Annual Review of Anthropology 51: 173–94.

Wilkie, Alex, and Mike Michael. 2016. “The Design Studio as a Centre of Synthesis.” In Studio Studies: Operations, Topologies & Displacements, edited by Ignacio Farías and Alex Wilkie, 25–39. London: Routledge.