Activism: Provocation

From the Series: Activism

From the Series: Activism

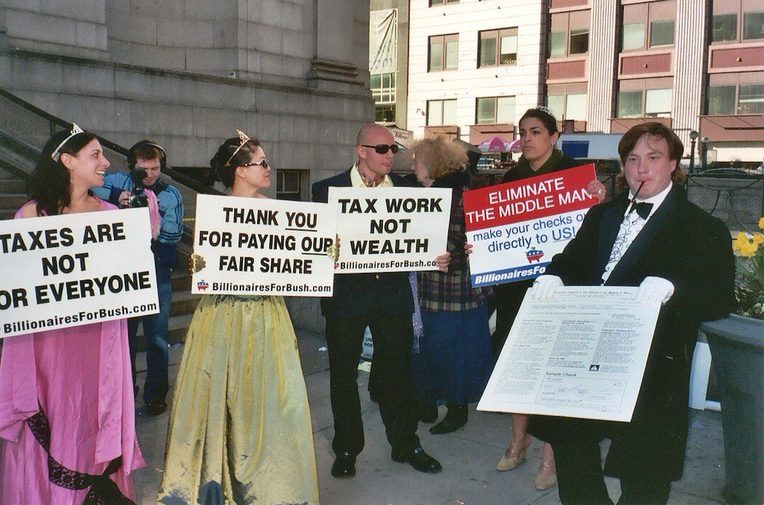

“Rock star” is the semantic gift American pundits bestowed on French economist Thomas Piketty as the English-language version of his book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, rose to the top of best-seller lists. Surging economic inequality—evident in the United States for several decades—is the “new hot topic,” proclaim media voices in the spring of 2014. Piketty’s deeply researched book traces the historic rise of the one percent in the United States as well as in Britain and France. Paul Krugman (in the New York Review of Books) terms Capital in the Twenty-First Century “a book that will change the way we think about society and the way we do economics.” Wealth inequality was almost hot, or briefly hot, in 2013 as well, when Robert Reich released his documentary film “Inequality for All.” Softening the ground a couple of years earlier were Occupy Wall Street, global anti-austerity protests, and the Arab Spring. Media mentions of economic inequality spiked in 2011 with the rapid spread of Occupy movements declaring “we are the 99 percent!” A few years earlier, media-savvy satirical activists such as the elegantly attired Billionaires for Bush (or Gore), Billionaires for Bush, and Billionaires for Bailouts also helped to nudge into public view wealth inequality and the role of big money in politics. In short, provocations via economic tome, documentary film, protests, occupations of public space, and satirical street theater. What makes any of them visible or invisible?

The Billionaire satirists’ provocations came with a dose of charm—subversive messages wrapped in ironic humor, delivered by activists in tuxedoes and top hats, ball gowns and tiaras. “Corporations Are People Too!’ was a favorite Billionaire slogan well before the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision nullified earlier restrictions on direct corporate donations to political campaigns. Adopting fictive personas and names such as Noah Countability, Tex Shelter, Lucinda Regulations, Ivan Aston Martin, Phil T. Rich, Iona Bigga Yacht, Alan Greenspend, and Meg A. Bucks, they waved professionally printed signs declaring “Leave No Billionaire Behind!” and “Widen the Income Gap!” and “Still Loyal to Big Oil” and Taxes Are Not for Everyone” and “Because we’re all in this together, sort of.” Their agenda? Campaign finance reform, progressive taxation, a strong social safety net, and restraint on monopolies. Today public figures such as Elizabeth Warren and Robert Reich have helped to bring such issues to the fore, though obstacles to progressive reforms through legislation appear formidable, thanks to the political influence of lobbyists and political campaign donors who are actual billionaires. Though plutocracy flourished again by the turn of the millennium, surging wealth inequality was seldom mentioned during the presidential campaigns of the 2000s. The satirical Billionaires, as I wrote in my 2013 book (No Billionaire Left Behind: Satirical Activism in America, p. 4) were “like canaries in a mine shaft, emitting warning signals ahead of dire trouble.”

It was not dire trouble, but “beautiful trouble”—another provocation—that was the aim of creative activists such as the Billionaires’ co-founder Andrew Boyd, the Yes Men, The Other 98%, and Reclaim the Streets. The 2012 book Beautiful Trouble, co-edited by Andrew Boyd and Dave Oswald Mitchell, is a 460-page compendium of activist tactics, design principles, theories, and case studies. The reader learns about creative petition delivery, flash mobs, culture jamming, invisible theater, hashtag politics, memes, the Harry Potter Alliance, teddy-bear catapult, and much more. It is almost anthropology!

For anthropologists, activism raises questions about ethnographic positionality, impact, possible overidentification with the groups studied, distinctions between theory and action, and epistemic politics. In a recent article in this journal, Michal Osterweil (“Rethinking Public Anthropology Through Epistemic Politics and Theoretical Practice,” 2013), argues for an “expanded notion of engagement” that moves beyond the divide between critical anthropology on the one hand, and “public, activist, or engaged anthropology” on the other (p. 599). A 2013 virtual issue of American Ethnologist, guest edited by Samuel Martínez, explores visibility and invisibility as “active processes, not merely empirical states or static qualities of appearance or nonappearance.”

Such a framework invites us to delve into how, when, and why particular networks or forms of activism appear in and fade out from media spotlights and political discourse, and to explore activists’ own tactics of concealment, disguise, and exhibition. The satirical activists among whom I have conducted research are themselves engaged in expert forms of knowledge production, deconstruction, and auto-critique, and they are as attuned as many anthropologists are to the emergent and evanescent. The Billionaires’ co-founder, Andrew Boyd, expresses a sense of cosmic irony and talks about “playing with meaning itself.” Anthropology indeed.

A final provocation: as pundits today seize on Piketty’s book and economic inequality as a “hot topic,” are they expanding political space for deep reforms or structural change? Or are they helping to mainstream American inequality in ways that might foreclose possibilities for progressive reform? Might more anthropologists join the economists who dominate public sphere discussions of riddles of economic fairness?

Boyd, Andrew and Dave Oswald Mitchell. 2012. Beautiful Trouble: A Toolkit for Revolution. New York and London: OR Books.

Haugerud, Angelique. 2013. No Billionaire Left Behind: Satirical Activism in America. Stanford University Press.

Krugman, Paul. 2014. “Why Economics Failed.” New York Times, May 2, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/02/opinion/krugman-why-economics-failed.html (accessed May 2, 2014).

Osterweil, Michal. 2013. “Rethinking Public Anthropology Through Epistemic Politics and Theoretical Practice.” Cultural Anthropology 28(4):598-620.

Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Belknap Press/Harvard University Press.