In this essay, I explore an event that inspired my interest in the performative aspects of making political claims. The images included here were made at the April 2012 opening of an exhibition at the Cultural Center of the University of Huamanga, which is located in the capital city of the Peruvian province of Ayacucho. At the time, I was eight months into a yearlong period of fieldwork. The human rights organization Aprodeh asked me to videotape the opening for their website and archive. The exhibition featured clothing that had been worn by “the disappeared,” those who were killed by state or paramilitary forces during the internal armed conflict in Peru between 1980 and 2000 and whose remains were disposed of in mass graves or otherwise inaccessible terrain. I arranged to accompany a group of relatives of people who had been disappeared to see the exhibited clothes, including some with whom I had previously worked at Anfasep, a local organization for victims’ families. During the previous months we had made a documentary film about their practices of remembering the conflict. Yet the opening was the first event that I had attended with victims’ relatives outside of my own project, which granted me an unfamiliar distance from what unfolded there.

As these women moved through the exhibition, they performed a scene of suffering without unease. With my camera in hand, I sensed that I could go in close to film facial and bodily expressions of anxiety and pain. It was as though I had left behind my own, perhaps overly self-conscious sense of guilt around gathering data for my own scholarly project. I became aligned with their desire to enlist the acknowledgment and support of broader audiences in their political struggle for justice. For once, my job was not to think about our interactions in terms of my own body of work, but to follow their lead and put their expressions into pictures.

The moving images I recorded that evening introduced me to the fluidity of coming closer and seeking distance, sometimes punctuated by palpable abruptness in moments of insecurity. The camera enlisted me in the joint effort of “memory activism” (Friedman 2017, 150), which is marked by mutual engagements between different subjectivities inhabiting a diverse set of roles. As John Jackson (2013) has pointed out, today’s anthropological collaborator is a self-aware subject, who crafts her own auto-ethnography even as she critically consumes what the ethnographer has to offer. Here, Jackson makes a case against Geertzian thick description as the anthropologist’s core practice and for something that has become thinner through the subject’s awareness. I share the view that ethnographic practice has gone through substantial transformations inspired by demands to be included in the process of knowledge production, but here I argue against the idea of thinness. As rich as the representations of a collaborator’s own awareness and agency may be, the anthropologist’s engagement with them can also bring the complexities that inhabit the realm of the intersubjective into view.

This selection of still images from the video material that I recorded at the opening offers a sensitive, but precise way of narrating the experience of engaging with victims’ relatives, forensic scientists, and representatives of the state at the exhibition in Ayacucho. Each frame occupies a space in a sequence of frames and signifies a moment that my memory has rendered meaningful. At the same time, the choice of frame allows me to highlight dynamics that emerged between people, places, and objects. At twenty-five frames per second, my six hours of video material yielded 540,000 frames, each of them a possible choice. Taking a photograph involves ”a collusion with the contingency of the world whereby something is selected out of the ‘vast disorder of objects’ and what is documented only ever occurs once” (Irving 2006, 27). Indeed, Roland Barthes (1981, 6) would have us wonder, “of all the objects in the world: why choose (why photograph) this object, this moment, rather than some other?”

Such questions, I have found, also apply to the selection of video stills. In integrating the process of image production with ethnographic practice, there are three instances where the researcher’s analytical work materializes. First, the moment the image is shot. Second, the moment the image is selected and edited. Third, the moment the image is arranged and/or circulated. It is precisely in this process of making choices that the production of anthropological knowledge inheres. The work of ethnographic photography, like that of ethnographic filmmaking or writing, can be understood as an analytical process in which the analysis is embodied in the crafting, slicing, and juxtaposing of material. For still images this means the choice of frame, the adjustment of color and light, the place that an image is given among other images, and the ways the image is placed in dialogue with other media and (con)texts. These different elements establish the rhythm through which memory is narrated. In this photo-essay, the addition of captions accelerates a particular kind of reading and accentuates points of irruption as well as moments of silence. Yet these captions do not seek to fix meaning so much as to evoke it.

Once displayed or circulated, images move between audiences and contexts by which they are reframed. The same images used here to complicate what might have been made simple may call up different meanings elsewhere. In a human-rights report, they may serve as truth-speaking evidence of loss and suffering. As such, the images may help to consolidate a shared and consensual memory. According to Deborah Poole and Isaías Rojas Pérez (2010), photographic images that are understood as self-evident and historical prepare “the perceptual grounds from which individual emotions and feelings can be interpolated as part of a collective moral engagement with the past.” Photographs can take part in processes that fix meaning in an effort to assert existential certainties.

The images that appear here do not speak for themselves or for others. Rather, they seek to evoke relationships between people, places, and objects in postconflict Peru. Articulated at the intersection of performance, visual narrative, and observation, these relationships are embedded in an effort to speak about transitional justice through a shared poetics of memory.

Note

The title of this photo-essay was inspired by “Curating the Activist Object,” a project of the Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change.

Download “Activist Objects: The Materiality and Meaning of Human Remains in Postconflict Peru” by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich as a pdf booklet.

Photos

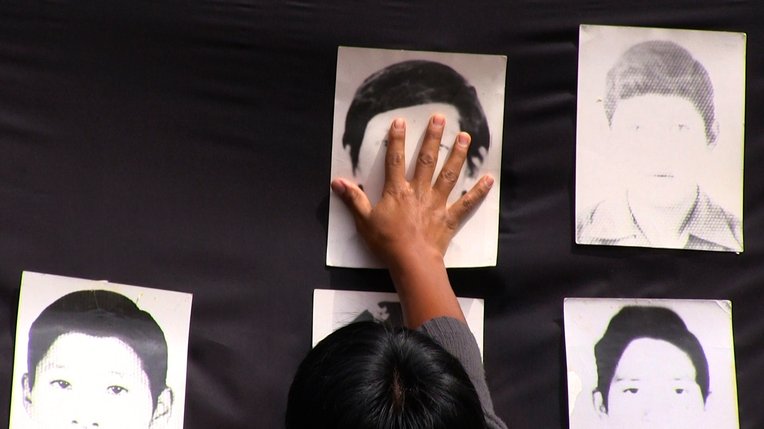

The missing. Pictures taken for ID cards are often the last remaining depiction of a disappeared family member. In areas with limited access to technology, these images often serve as testament to the person’s existence; what was formerly used to prove citizenship is turned into a symbol of absence. After arranging the photographs on black sheets, a commemoration ceremony is held. Candles are lit, accompanied by the hymn ”Hasta cuándo, hijo perdido” (Until when, Lost Son). Speaking the global language of human rights, these images and the ways they are embedded in symbolic expressions of loss bridge personal and collective struggles against indifference and oblivion.

La Hoyada, a place turned evidence. The hill to the right marks the boundary between pueblos jóvenes (new urban settlements) and the military barracks known as Los Cabitos 51. Human-rights organizations and relatives of the disappeared claim that the sixteen-acre field of La Hoyada, which lies in between military and urban lands, is the biggest mass grave in Peru. From here, the Peruvian armed forces directed their regional counterinsurgency war against the Peruvian Communist Party, also known as Shining Path. What today is known as the Peruvian internal armed conflict began in 1980 with Shining Path launching its so-called people’s war. Based in the city of Huamanga and initially supported by large factions of society, Shining Path declared the Peruvian state the enemy of the people. Three presidents responded to their insurgency by sending the armed forces, police, and clandestine paramilitary units to conduct a brutal counterinsurgency campaign. Officially, this conflict lasted until the year 2000 when Alberto Fujimori’s government fell after ten years of corrupt autocracy and, with it, a whole system built on fear and state repression.

Twenty years of insurgent and state violence are remembered as the longest and most costly conflict in terms of human casualties, forced migration, and material loss since the founding of the republic. The Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission counts 69,280 people killed or disappeared and around 430,000 people displaced. It found the state forces to be responsible for 37 percent of the conflict’s fatalities, as well as systematic human-rights violations including torture, forced disappearances, (sexual) abuse, and vandalism. But 54 percent of all deaths are ascribed to Shining Path. This number is attributed to Shining Path’s messianic ideology, which glorified violence and death; this, in turn, legitimized the indiscriminate use of violence by agents of the state. The tragedy lies in the ways that the complexities of the conflict have been reduced to simplified and polarized depictions of the past, often favoring the army and government while brushing aside the systematic violence they inflicted on a mainly Quechua-speaking population.

Ayacucho exige (Ayacucho demands). Memory activism is a term used by human-rights activists, victims’ relatives, and researchers to refer to mourning in its most political form, “where sorrow is publically articulated in demands for social, economic, and legal recognition” (Bernedo 2012, 2). As Primo Levi (1988, 12) noted, there are people affected by the experience of violence who “tend to block out the memory so as to not renew the pain.” Others, however, have made the act of telling the project around which their lives revolve. Visuality plays a crucial role in the construction of postconflict narratives and identities—not only to remain visible, but also to be loud. Photographs, banners, logos, colors, and flowers offer the chance to render their truths real and graspable.

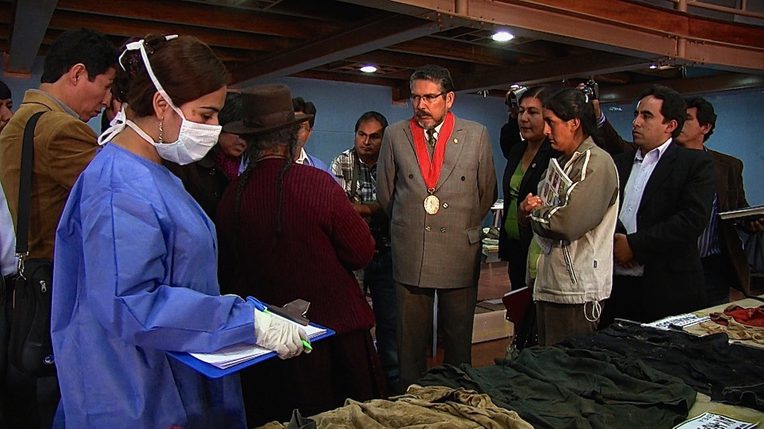

AY-HU-AY-SV/F31-C01: NN. NN means No Name. This is the category under which unidentified bones are stored in the cellars of Peruvian ministries in Lima and other regional capitals. Masses of cartons filled with fragments of skeletons and clothes stacked on top of each other are palpable legacies of the conflict. In an effort to systematically organize all of the objects found during exhumations, they are given numbers that allow them to be traced back to the place, time, and other objects they were exhumed with. Victoria, a relative of a disappeared person, explains: “They are objects that seek to break out of the forensic box into a coffin that is marked with a name, not a number. The exhibition of clothes, which are the only items that allow us to recognize our relatives, is a means to this end.” This sought-after transformation is a metaphor for the challenges that the transitional justice system faces, namely to identify and bring the missing pieces back together.

Once recognized, analyzed, and identified, bones and clothing can be traced to an individual person and his or her story of violence and death. In one relative’s words: “They are the legal evidence against those responsible for disappearing thousands of men and women. This evidence will never go away unless the people responsible face up to it and take responsibility for their actions. All we want is justice.” However, many years of searching have passed with little progress. A nongovernmental organization of forensic anthropologists identified more than five hundred clandestine burial sites that are still waiting to be exhumed.

Gazing hope. On the one hand, bones and clothing constitute the legal foundations of the relatives’ claim for justice. On the other hand, they carry symbolic meaning that indexes the pain and suffering the relatives have endured since their family members’s disappearance. I was told again and again that giving the dead a Christian burial would provide the living with the possibility of closure, even though the dead will remain dead.

Close-ups of unknown stories. The red jumper.

Close-ups of unknown stories. Male underpants.

Close-ups of unknown stories. Broken shoes.

The precarity of hope. Less than a decade ago, DNA analysis arrived in Ayacucho. Before that, victims’ relatives were not aware that laboratory testing could trace human remains back to a person. Felicitas, who joined Anfasep after her husband’s disappearance in 1984, explains: “If we knew, we would have collected the bones we found. We would have saved and stored them somewhere somehow, all of them.” Peru does not have a laboratory that can provide DNA services affordably; therefore, samples are sent to Colombia or Costa Rica. Without these tests, though, the recognition of clothes is meaningless. A forensic anthropologist explains: “Not all clothes belong to the right bones. Prisoners used to put on the clothes of those who were already dead since, at night, it gets bitterly cold. In later years, soldiers were ordered to swap prisoners’ clothes precisely to complicate the identification process of human remains.” Only when the ante mortem information matches the post mortem information can the victim’s status be changed to identified. Meanwhile, the perpetual lack of funds, expert personnel, and time indicate that hope is a precarious good.

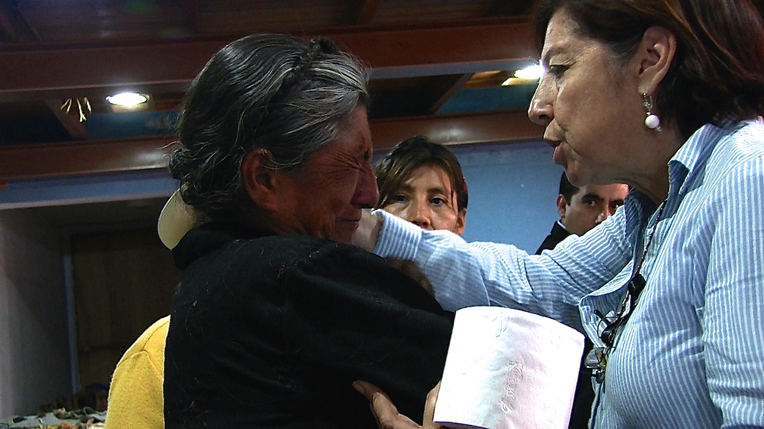

Re-encountering loved ones through remnants of clothing. On this day, the clothes from box AY-HU-AY-SV/F31-C01 were recognized by a woman who says she is the mother of the young man who once wore the green jumper on display. Here, she stands next to the exhibition table, about to be photographed by a forensic scientist. The photograph will be added to the case folder with the same designation. She will fill out a form that will allow her to order genetic tests that are only for victims’ relatives who have recognized the clothes of their loved ones.

Certainty, when it hits.

AY-HU-AY-SV/F31-C01: the politics of (in)visibility. The public attorney to the relative: “In the name of the republic, I express our deepest condolences for your loss. This certainty may bring an end to your painful search and that of your family. There is still a lot to be done, but we have taken our responsibility seriously.”

The human rights activist to the press: “The tragic presence of these unidentified bodies stains our government and our politicians with shame. They underline the importance of our nation-state acknowledging the crimes committed during the conflict and expediting the return of the disappeared to their families in order to contribute to the process of social healing. Our government has not really taken on this responsibility.”

The journalist to the microphone: “Reporting live from the Cultural Center of the University of Huamanga, tragedies that happened more than three decades ago finally find closure. We are speaking to a relative, who found the green jumper that her disappeared son wore in 1983 when he was taken by force by paramilitary soldiers. How does it feel to be reunited with a piece of your son after so many years?”

The social anthropologist to the relative: “I am very sorry for your loss. Perhaps you could describe who your son was and how he disappeared. I would like to know more about what finding your son’s clothing means to you and to Anfasep. Can we arrange a longer conversation after all of this?”

The forensic scientist to the crowd: “Please let the lady calm down and give us some space to do our work. Mamita, we will now fill out this form so we can register the identification of your son’s clothing. Then we can take your saliva sample. Your full name and ID number, please . . .”

Elena Gonzalez and her sister. Elena (left), the president of Anfasep at the time, asked me to take this picture after the relatives visited the exhibition. Along with her sister, Elena was looking for her father’s clothes. He was wearing a blue jumper when they took him. In 1984, the armed forces entered their house and took him away in the middle of the night and he never returned. Their mother went to ask for him at the gates of Los Cabitos, almost every day for several years. She baked cakes for the soldiers in exchange for information and even though she did that for months, nothing came of it. When Elena asked me to take the picture, her sister objected: “But my face is all tear-stained.” Elena replied, “That is necessary.”

References

Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang. Originally published in 1980.

Friedman, Rebekka. 2017. Competing Memories: Truth and Reconciliation in Sierra Leone and Peru. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Irving, Andrew. 2006. “The Skin of the City.” Anthropological Yearbook of European Cultures 15: 9–36.

Jackson, John L., Jr. 2013. Thin Description: Ethnography and the African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Levi, Primo. 1988. The Drowned and the Saved. Translated by Raymond Rosenthal. New York: Summit Books. Originally published in 1986.

Poole, Deborah, and Isaias Rojas Pérez, Isaias. 2010. “Memories of Reconciliation: Photography and Memory in Postwar Peru.” e-misferica 7, no. 2.