Andeans in the City: The “Toma de Lima” and the Historical Defiance of January 2023

From the Series: The "Marcha a Lima" against the Denial of Modern Political Rights

From the Series: The "Marcha a Lima" against the Denial of Modern Political Rights

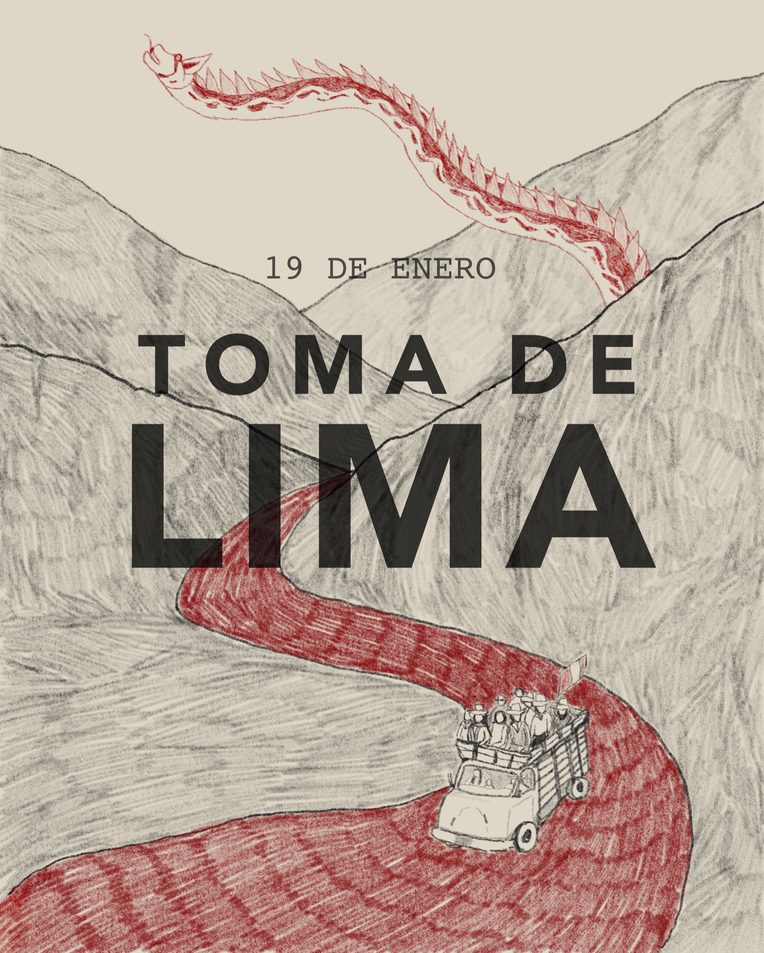

January 18th marks the anniversary of the Spanish foundation of Lima, the capital city of Peru and former center of the colonial Viceroyalty. As usual, authorities celebrate the date by highlighting isolated episodes of its history, mostly from the colonial and republican periods. They also stress the Hispanic heritage of the city, in an unconvincing effort to erase its pre-Hispanic settlement. Nonetheless, this anniversary was different. Hundreds (or perhaps thousands) of people from the interior arrived to the capital to participate in the “Toma de Lima,” a massive demonstration against the ultra-conservative government coalition led by President Dina Boluarte.

The demonstrators arrived in trucks and buses, occupying Lima for several days, and propelling long-term anxieties for Limeños and the central government, who responded to their presence with fear and violence. As I explain in this essay, the “Toma de Lima” should be understood not only as a single protest but within a broader arc of tension between the capital city and the regions, which can be traced back at least a century and a half ago. The massive presence of individuals from peasant and Indigenous ancestry in the capital also evoked previous episodes of mass rural migration and mobilizations in a city whose elites desperately aim to erase its Andean heritage and present themselves as white.

The current resistance exhibited by the elites to recognize the multicultural profile of the city began in its modern form in the mid-nineteenth century, when liberal ideas contributed to dismantle the old regime in Europe, Latin America, and elsewhere. In Peru, the Indigenous head tax was abolished in 1854, prompting a massive migration from the highlands to coastal areas. This also accelerated the decline of el interior (the highlands) while Lima, the exterior-looking metropole, concentrated power and the wealth obtained from the recently discovered guano de las islas. Consequently, when Andean or Amazonian Indigenous representatives (emisarios) wanted to be heard by the central government, they had to travel to Lima where they were exposed to mistreatment, and their efforts to solve local issues were met with indifference by central authorities.

The Marcha de los Cuatro Suyos in 2001 was a turning point in this relationship. For the first time, an organized protest sought to bring individuals from the whole country (represented as the four parts [suyos] that organized the Inca Empire) to the capital to prevent President Alberto Fujimori from renewing his corrupt presidency. Mobilizing citizens nationwide was a major challenge. For several months, neighborhoods, organizations, and communities collected money to cover travel and lodging. The call for the march was broadcast by radio; other media coverage had been seized by the government.

Hundreds of people flocked to Lima in late July 2001. Organizers were overwhelmed by logistic obstacles, and public squares (like Plaza Manco Capac, icon of workers protests and close to my childhood neighborhood) were transformed into encampments. On July 28th, demonstrators marched downtown to impede the presidential ceremonies commemorating Peruvian independence. In the end, the intelligence agency orchestrated a fire in the National Bank, blaming protesters in order to criminalize the protest (and killing six security guards trapped in the fire). Fujimori retained power, but the Marcha de los Cuatro Suyos set an important precedent about the capacity of the “rest of the country” to shape national and Limeño politics.

Twenty years later, the “Toma de Lima” summoned the presence of highlanders to the capital. This time, most of them came from the Southern Andes, from Quechua and Aymara regions with a history of confrontations with central Lima governments. During one of those confrontations, known as the Rebelión de Huancané (1866), the national army crushed the rebellion, executed the rebels, and took their children to the urban areas to be sold as domestic servants. This did not discourage protesters, who continued organizing to expose the abuse of landowners and regional state officers.

Those who arrived in Lima in January 2023 did so with a mix of grief and excitement. Like their predecessors, these new emisarios had the responsibility to express their rejection to the brutal state repressive actions in the region, where the army killed dozens of citizens. Like their ancestors, they traveled to the coast in trucks and were received in Lima by fellow migrants and local organizations. Plaza Manco Capac served again as a site to host them along with public universities and peasant organizations. Solidarity campaigns provided shelter and food to the newcomers.

Unsurprisingly, the central government met travelers with animosity. Even before they arrived, caravans of buses and trucks were stopped and passengers were required to show official identification. Once in Lima, they faced continuous harassment from security forces. The police forced their entry into Universidad San Marcos (where travelers had been sheltered) and threatened the Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería with a similar action—both are public institutions. Leaders of the “Toma de Lima” were arrested under the charge of terrorism. In the following days, authorities and the far-right media portrayed the march as a “terrorist act,” conjuring the years of political violence in the 1980s and 1990s.

The 2023 “Toma de Lima” once again brought protests from highland regions to Lima, the capital city. This time around, the protest exposed the illegitimacy of the government coalition and the need of police brutality to maintain its power. The occupation of the capital city was also a public defiance of a social and cultural order that historically ignored the political agency of national fellows del interior del país, even refusing their recognition as citizens. It is hard to say how this political crisis will end, but the “Toma de Lima” has confirmed that the socio-cultural divide between the capital and the rest of the country remains as a central, unresolved, and lethal problem in the country, with more than sixty victims only in the past three months.