What if we approached our pedagogical and scholarly engagements with ethnographic cinemas as a series of curatorial exercises in seeing, as a practice of second-order observations of film fragments? What if we approached these fragments as shards of curatorial inquiries into the genre of the ethnographic film? What if, finally, these cinematic fragments were arrayed into an assemblage of stills and moving-images?

In the context of 1920s Mexico such “curatorial design” (Elhaik and Marcus 2019), linked to a cohort of fascinating personae, would have been copiously rewarded. In this scene, we would encounter Manuel Gamio’s cinematic-theatrical mise-en-scenes, Miguel Covarrubias’s films on dance in Bali, and the actualités of both Salvador Toscano and the Alva brothers whose moving-images draw our attention to Mexican revolutionary politico-visual culture. Moreover, we do know that a few revolutionaries managed to make it to Hollywood where they found a career playing Mexican revolutionaries (Orellana 2003). We would also overhear debates on the problematic nature of the work of those opérateurs, such as Gabriel Veyre, who were dispatched by the Lumiere brothers across the world to record the lives of others whose difference they captured culturally.1

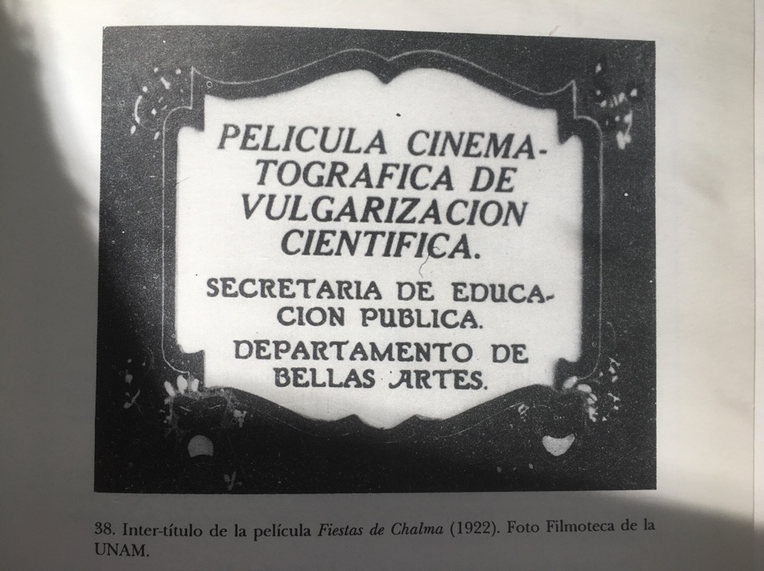

Early ethnographic cinema continues to belong to a “Beaux-Arts system” (De Duve 2018). In the very same way that Edward S. Curtis’s compositions with skulls at the bottom of the frame reminds the educated viewer of the vanitas of Baroque painting (figure 1), the beautiful ornamental intertitles in the Gamio-inspired Fiestas de Chalma (1922), an ethnographic film produced by the Departamento de Bellas Artes (Department of Fine Arts or Beaux Arts), suggests a pictorial tradition with a rich traffic of conventions between disciplinary anthropology and art history.

“Mexperimental” (González and Lerner 1998) ethnographic cinema from the 1920s was a complex tradition with one foot already in the avant-garde, and the other still in Bellas Artes. Take a moment and look at the delicate and ornamental borders in the frame, as well as the reference to Bellas Artes or Fine Arts (figure 2).

Fiestas de Chalma is therefore part of both the traditions of ethnographic film and the anthropology of art. As Baxstrom and Meyers (2015) have convincingly shown, there is more to 1922 than Flaherty’s canonical and commercially successful docudrama Nanook of the North, usually thought to be the foundational ethnographic film. Through a reconfiguration of Benjamin Christensen’s film Haxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages (1922), Baxstrom and Meyers develop an innovative argument in which the authors invite us to think of Haxan as yet another “anthropological and cinematic object” afforded by the scientific and artistic “milieu” of 1922.

Manuel Gamio—“father” of Mexican anthropology and archeology as monumentally indicated by the commemorative plaque in the Plaza named after him in Mexico City’s Zocalo—deeply valued the use of film in social scientific research. The few extant films made under his aegis were many as were the films directly inspired by both his excavations and ethnographic studies. Of course, the use of photography and cinema was common in the global and cosmopolitan anthropology of those years, but Gamio expanded film toward other artistic traditions and media. For instance, while conducting his watershed study of the populations in the Valley of Teotihuacán he also staged a major open-air mise-en-scène that reenacted the life of the fascinating Tlaxcalan warrior Tlahuicole (1925). Although not a film, Tlahuicole was a play that aimed at rectifying the gross scientific and historical representations by Hollywood-inspired filmmakers and “fake nationalists” (De los Reyes 1991) and had a cinematic afterlife. Indeed, the inaugural performance on the site of the major archeological complex of Teotihuacán was both filmed and later shown in a theatrical setting in Los Angeles.

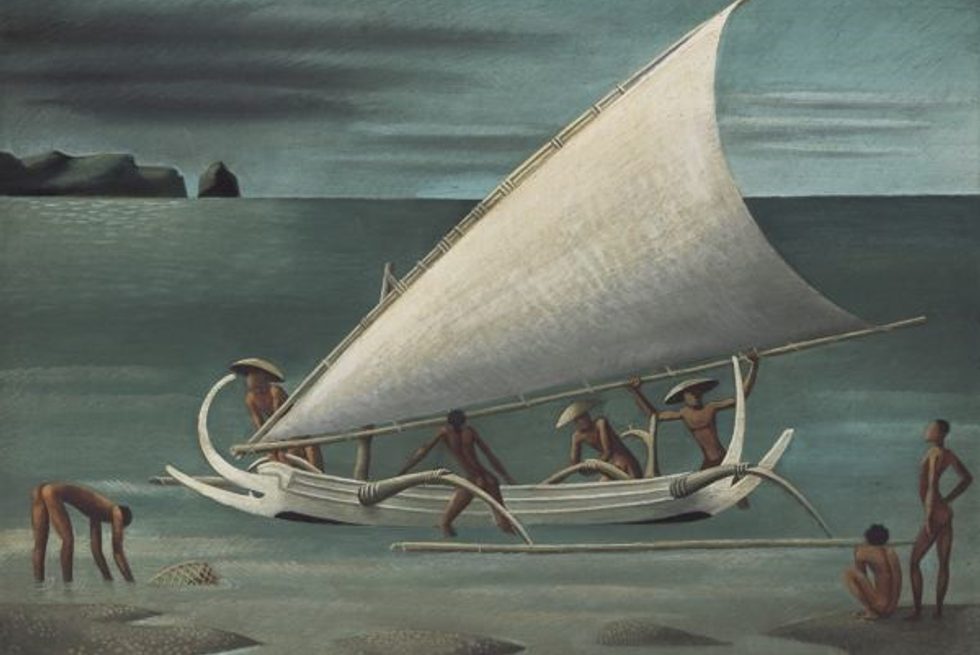

While Gamio’s corrective cinematic-artistic experiments are ultimately too nationalist for my post-Mexicanist taste (see Elhaik 2016), Miguel Covarrubias’s vignettes of dance in Bali offer both a canonical cross-cultural version of ethnographic film, and a counterpoint to the deployment of nationalist aesthetics in 1920s and 1930s cinema in Mexico. Covarrubias, along with his wife the dancer and choreographer Rosa Rolanda, was an intriguing amateur anthropologist and visual artist who was slightly different from many of his Mexican peers in that he did express a mode of curiosity beyond the militant nationalist expectations of Gamio’s ideological program of “forjar una patria.” Forging a homeland became the ethical substance of Mexican anthropology. In fact, this essay was initially inspired by a recent walk in the Centro Historico where I went to visit Plaza Gamio, inaugurated in 2018 to honor his oeuvre. What if Gamio was instead the unexpected precursor to a mode of film curation, the aim of which is less to build a motherland than to speculate and cogitate with film fragments?

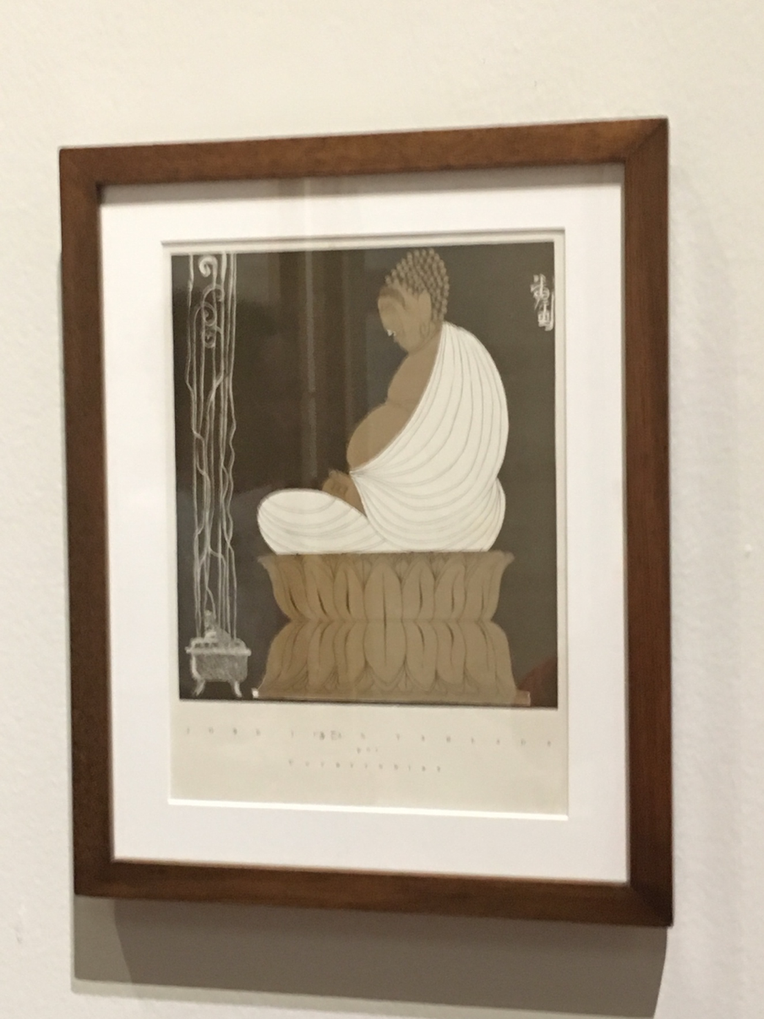

A final implication: this film curatorial approach enables us to reconfigure the very notion of cross-cultural juxtaposition (Marcus and Fischer 1986) in that Covarrubias’s Bali films serve as a counterpoint to Gamio’s nationalist objectives. I had come across Gamio’s commemorative plaque after having visited Pasajero 21/Passenger 21, the ongoing exhibition at Bellas Artes on artist José Juan Tablada’s visions of Japan. Amid drawings, paintings, poetry manuscripts, and film fragments indexing Tablada’s travels and encounters with Japan, the visitor can also pause to look at Covarrubias’s hilarious caricatures of his friend Tablada’s “Japonismo” in which a deformed Tablada is shown sitting in the lotus position and dressed in a Kimono (figure 3).

While I wondered what a caricature by Tablada of a Balinese Covarrubias would look like, I found myself thinking that curating ethnographic film fragments demands from us to be fluent in Mexico’s art-historical heritage, modernist and contemporary, beyond the nationalist ethos of Gamio toward a curatorial horizon that includes Tablada’s Japan and Covarrubias’s Bali. As I have shown elsewhere (Elhaik 2016), this type of film curatorial approach opens a horizon of viewing and experiencing cinema beyond conventional South-South dialogues. Like the logic of the gift, film fragments move in zigzags and are always displaced. Yet, unlike gifts, they are seldom reciprocated in the form of returns to the place of origin. Unusual gifts, fragments are elements that can only be reassembled anew in the context of trans-regional genealogies of media. Covarrubias’s Bali films and Gamio’s theatrical and cinematic experiments are such unusual gifts.

Note

1. Veyre’s Desayuno de Indios expresses such classical cross-cultural way of seeing.

References

Baxstrom, Richard, and Todd Meyers. 2015. Realizing the Witch: Science, Cinema, and the Mastery of the Invisible. Fordham, N.Y.: Fordham University Press.

De Duve, Thierry. 2018. Aesthetics at Large: Art, Ethics, Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

De los Reyes, Aurelio. 1991. Manuel Gamio y el cine. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Elhaik, Tarek. 2016. The Incurable-Image: Curating Post-Mexican Film and Media Arts. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Elhaik, Tarek, and George Marcus. 2019. “Curatorial Designs in the Poetics and Politics of Ethnography Today: Act II.” In The Anthropologist As Curator, edited by Roger Sansi, 17–34. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

González, Rita, and Jesse Lerner. 1998. Mexperimental Cinema: Sixty Years of Avant-Garde Media Arts in Mexico. Santa Monica, Calif.: Smart Art.

Marcus, George E., and Michael M. J. Fischer. 1986. Anthropology as Cultural Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Orellana, Margarita de. 2003. El cine norteamericano de la Revolución Mexicana (1911–1917). Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva.