This post builds on the research article “Anticipatory States: Tsunami, War, and Insecurity in Sri Lanka,” which was published in the May 2015 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editorial Footnotes

Affective, psychological, and political effects of disasters and their attendant anticipatory states in Cultural Anthropology are central the Hot Spots series “3.11 Politics in Disaster Japan: Fear and Anger, Possibility and Hope” (2011), edited by David H. Slater. This series includes David S. Sprague’s “Mapping Anxiety,” Keiko Nishimura’s “On Exhaustion, Self-Censorship and Affective Community,” David H. Slater’s “Neoliberal Radio/Activity and Contagion,” and Sharon Hayashi’s “Representational Discontent.” Conversations around disaster also find a home in Grant Jun Otsuki’s Field Note series, “Disaster” (2013), with a Provocation by Ben MacMahan, Translation by Vivian Choi, Intervention by Anne Allison, and Integration by Kim Fortun.

Several Cultural Anthropology articles add insight into the temporalization of disaster, including Adriana Petryna’s “Sarcophagus: Chernobyl in Historical Light” (1995), Andrew Lakoff’s “The Generic Biothreat, or, How We Became Unprepared” (2008), and Chelsey Kivland’s “On Accidental Recoveries and Predictable Disasters: The Haitian Earthquake Three Years Later” (2014).

About the Author

Dr. Choi earned her PhD in cultural anthropology at the University of California, Davis. She is currently a postdoctoral associate at the University of Tennessee, in the Department of Anthropology and the Program on Disasters, Displacement, and Human Rights. Prior to that she was an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at the Society for the Humanities and the Department of Science and Technology Studies at Cornell University. She is currently working on her first book, tentatively titled Disaster Nationalism: Tsunami and Civil War in Sri Lanka. Vivian’s work has appeared in two edited volumes on disaster (Tsunami in a Time of War: Aid, Activism, and Reconstruction in Sri Lanka and Aceh and Dynamics of Disaster: Lessons on Risk, Response, and Recovery) and she is co-authoring a chapter on disaster and science and technology studies for a science and technology studies handbook. She is co-editor with Michelle Stewart of the online Photo Essay section of Cultural Anthropology.

Interview with Vivian Choi

Ann Iwashita: What led you to your work on this topic, in this place?

Vivian Choi: Before starting graduate school, I lived in Sri Lanka on a Fulbright Fellowship. I was there in 2003–2004, following the signing of the 2002 ceasefire agreement between the government of Sri Lanka and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). At that time, I was interested in women’s experiences of the war and displacement, and I worked with the Women and Media Collective, a fantastic group of women dedicated to feminist and women’s issues in Sri Lanka. At first it seemed an opportune time to be there; security was relaxed and it was a really hopeful moment, in terms of the conflict, for many people I met. Yet during my time there, the hope that I had felt and seen when I first arrived seemed to wane. Internal politics with the Sri Lankan government became increasingly fraught; the eastern bloc of the LTTE’s territorial claim broke off under the leadership of Karuna, dealing major blow to the LTTE. Then the tsunami happened in December 2004. The disaster changed things. So much so that when I returned that summer for preliminary research, I was particularly interested in new disaster management technologies and infrastructures, and how the implementation of those technologies played out in tsunami-affected regions. I went back in 2006 after Sri Lanka had sworn in a new president, Mahinda Rajapakse, who had run on a platform to end war.

In 2008, I returned to complete my dissertation fieldwork. Of course I knew the war was significant in terms of understanding the unfolding of the tsunami, and I did have an interest in the relationship between human-made and so-called “natural” disaster. But my time there was so deeply impacted by the war, its controversial ending, and the enduring forms of insecurity on the east coast—a region that had begun being “liberated” by government forces in 2007, two years before the end of the war—that my research ended up focusing on ways to talk about how the tsunami and the war articulated in certain moments together, rather than the war being the social context on which the effects of the tsunami played out.

AI: What was it like to live in an area that was made anticipatory by war and tsunami: the feeling among people and in you, in your own body? What (new) relations were drawn between people and the sea, people and the earth, people and the war?

VC: A lot of my writing comes from a feeling and a place of tension, and indeed, anticipation. Living in the Eastern Province in the final months of the war, especially, was very tense. Though we were far away from where the battle was being fought up North in the country, there was a palpable and uncomfortable sense that the government was going to defeat the LTTE. The North was off limits to independent journalists and humanitarian aid organizations. The Tigers were accused of using civilians as human shields and the government was accused of shelling and bombing civilians and hospitals. My friends and interlocutors in the East conveyed to me that they were worried for those civilians, that they were suffering much for them.

When the war ended, there was a self-conscious sense of sadness in the East, opposite the jubilation we saw expressed in other parts of the country on television. As I highlight in the article, people would tell me their feelings of sadness, but very carefully and quietly, for one never knew who could be listening. It wasn’t only Tamils who felt sad. Muslims living on the coast also told me that there were concerned for their futures amidst a Sinhala Buddhist hegemony. There was also doubt that the war was over; people felt that the war could start up again, just like it had over the last twenty-five years.

Just as many people felt the war could erupt again, they also felt that another tsunami was absolutely possible. The very fact that a tsunami actually did strike Sri Lanka forever shifted the horizon of what was possible. People had become aware of the fact that earthquakes occur regularly off the coast of Indonesia, and they began to pay attention to the news or seek word of the news from friends and family. While I was in Sri Lanka, they experienced their very own earthquake for the very first time. Then the solar eclipse occurred, and speculations were made about how the gravitational pull from the eclipse would cause tectonic plates to shift and would create an earthquake and then a tsunami.

Other physical markers such as the warning towers, evacuation route signs, ruined homes, and upturned wells served as reminders of the tsunami in the past and as something that can happen again, just as checkpoints and the ever-present Special Task Force very overtly remind people that insecurity and violence are also ever-present, even though the war was over and the LTTE was defeated. So the very possibility of tsunami and war, having already happened (rather than being an imagination or fantasy of a disastrous future) created the conditions of anticipation and all sorts of other tensions.

AI: What were some stories people shared about the tsunami, in terms of how it affected them personally, how they witnessed the sea that day? What did people, who presumably were not yet reliant on the non-operational warning towers, express were key indicators of a tsunami?

VC: Prior to December 2004, many Sri Lankans lamented that they had no idea about tsunamis. Everyone was caught off-guard. Before a tsunami occurs, the tide gets sucked out really far, exposing the sea floor, and then the giant waves come crashing back. When this happened in 2004, many curious Sri Lankans actually followed the water out, bewildered by the fish and other marine life left exposed by the impending tsunami. This proved disastrous.

In terms of how the tsunami affected people personally, well, the magnitude of that is sort of unrepresentable. Everyone has stories, certainly. One of my good friends lost fourteen members of his family, another family lost their mother, another their two children—everyone, it seems, lost someone. I was also told miraculous stories of survival, of being swept up by the water and waking up in a hospital, or seeking refuge in a refrigerator, or barely escaping the black sky of water. People never failed to mention the weather the day of the tsunami—cloudy and gray, rainy.

I am writing about these “sensory infrastructures” (that’s what I’m calling them for now) in another piece—had I another six-thousand words, I could have included it in this article, as this aspect is sort of the corollary to it. By sensory infrastructures, I mean the ways in which people are attuned to their environment—whether it is recognizing the color of the sky, windy days, the sounds of birds chirping and other animal behaviors. And these sensory infrastructures stem from the fact that perhaps state infrastructures are not always reliable.

During our conversation, Dr. Choi and I began a discussion on the semi-functional tsunami warning towers and their effects on the practices with, imaginations of, and bodily attunements to the sea. Her thoughts, and additional readings that inform what she terms “the reaches of disaster nationalism,” are included below.

VC: The early warning towers serve to remind people, certainly, that another tsunami could happen again. As I mentioned in the article, there was profound ambivalence about the towers. On the one hand, people were happy that they had been constructed; they were happy that something was there and that the government was doing something about the potential tsunamis. On the other hand, people hardly trusted them to work, in part because they hardly trusted the state to properly execute and care for them. This combination of pleasure and skepticism is structured upon a desire to be cared for, by people living in an area that had been long-neglected, and a cynicism of the state that stems from a long history of war and violence in the region, where many endured the terrors of both the government and the LTTE.

I am still sussing out both the utility and the limits of thinking with biopolitical forces and dynamics in the context of disaster nationalism that I am describing in Sri Lanka. Anticipatory practices are not strictly dictated by state’s technologies of disaster nationalism. They also stem from practices of life and survival—practices of endurance—that are subtler and not necessarily revelatory but vital nevertheless. This is a type of lateral agency (see Berlant 2011) that cannot necessarily be completely explained from an analytic of biopolitics. If a person chooses to run, or take heed of the warning system, I hesitate to attribute it all to a form of disciplinary power. So while I wouldn’t deny that there is a shift in behavior in relation to the towers, to the possibility of the tsunami, and to the state, I wouldn’t credit it all to the construction of a new warning system. Even in “Society Must be Defended,” Foucault (2003, 254) mentions that biopower that is in excess of sovereign right makes it “technologically and politically possible for man not only to manage life but to make it proliferate.”

There is much much more to write about this, but I’ll cut myself off here and just say that the reaches of disaster nationalism is the aim of my broader project, of which this essay is a part.

Additional Readings

Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Foucault, Michel. 2003. “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the College de France, 1975–1976. New York: Picador.

Yael Navarro-Yashin. 2002. Faces of the State: Secularism and Public Life in Turkey. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Das, Veena. 2007. Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Povinelli, Elizabeth. 2011. Economies of Abandonment: Social Belonging and Endurance in Late Liberalism. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Hastrup, Frida. 2011. Weathering the World: Recovery in the Wake of the Tsunami in a Tamil Fishing Village. Oxford: Berghahn.

Media

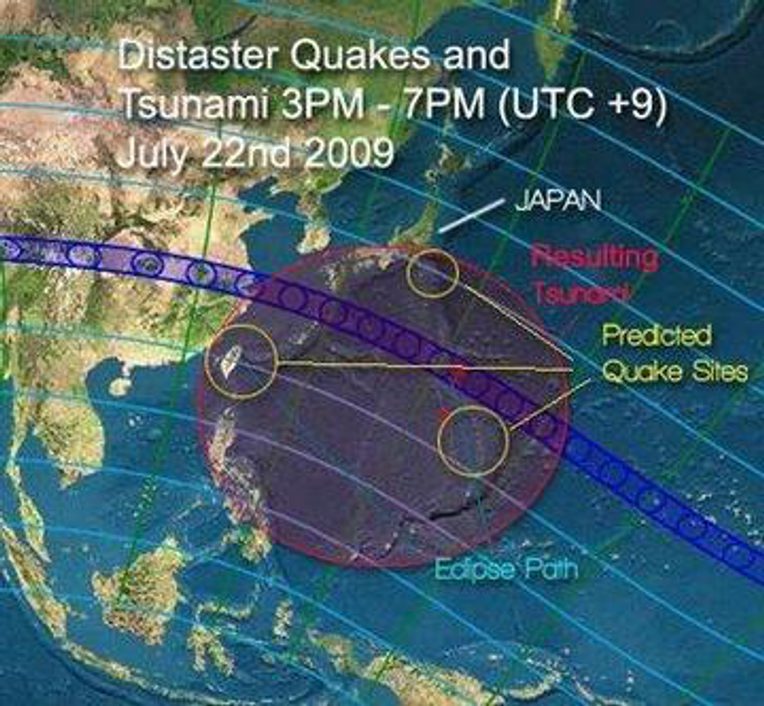

An investigative website debunks an email circulated in April 2009 warning of a July earthquake and disaster. The story included the image below.

The political cartoon below appeared in the Sri Lankan English newspaper almost eight years after the tsunami and nearly three years after the “end” of the war. The cartoon was published the day after an 8.6 magnitude earthquake struck off the coast of Aceh, inducing a series of tsunami warnings across countries bordering the Indian Ocean. Despite the government’s relocation to the city of Colombo and its investment in new disaster warning technologies, the official warning in Sri Lanka was issued after the time the tsunami would have hit shorelines and became indicative of the functioning of disaster response technologies, communications, and organization.

The government was also indicted in some of the fifty-six reported disappearances, kidnappings, and deaths that had occurred in the first six months of 2012. White vans were associated with these abductions and were thought to be connected to newly inspired Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism that had come with the defeat of the Tigers, and the manifestation of an as-yet unrestrained anti-Muslim movement.