Articulating the Invisible: Ebola Beyond Witchcraft in Sierra Leone

From the Series: Ebola in Perspective

From the Series: Ebola in Perspective

Sierra Leoneans use the language of witchcraft to describe the evils of living antisocially, with witches the epitome of the inhuman behaviors of isolation, selfishness, and malice. Witches control an invisible world and grow fat and wealthy through the bodily consumption of people and the destruction of their sociality by spreading fear and mistrust. The special danger of Ebola is that it threatens communal life in exactly the same way. It is now so dangerous that it menaces the powerful that attempt to control it.

In mid-June, just as the virus began spreading, a popular joke circulated the capital of Freetown. In it, a man boards a crowded poda-poda, one of the country’s ubiquitous minibus taxis, and settles in for the long ride from Kenema to Freetown. Now the epicenter of the country’s epidemic, Kenema houses the main Ebola testing facility. Annoyed at being crammed into an uncomfortably small space for a long journey, the man begins a loud conversation on his cell phone. “Hello!” he says, initiating an initially innocuous conversation. And then comes the reveal: “I almost forgot to mention: I just came from the clinic and I have my blood test results. They say I have Ebola!” Upon hearing this, the driver slams on the breaks and leaps out of the poda-poda, followed quickly by screaming passengers, who crawl over each other to escape, some climbing out of windows and taking off at a run into the bush. He stretches his legs and smiles, enjoying his newfound space.

My friend giggled breathlessly as she regaled us, bouncing her baby girl on one knee as we sat in the shade at a local café. Our server approached and, startled, the baby quailed. Her father admonished her with, “Don’t worry little one, she doesn’t have Ebola!” as he handed his daughter to the smiling waitress for a cuddle. The mood was light, punctuated often by contact: passing the baby, handshakes for friends who were also out for lunch, tasting each other’s food. It was as though through determined acts of human communality—feeding, laughing, touching knees around the small table—that Ebola could be made nothing more than a distant rumor, something which acts of intimate everyday living proved did not, could not exist.

Less than one month later, the narrative of the virus had changed completely. Another friend had taken a position coordinating public outreach for the Ministry of Health and had fielded disturbing questions during a long information session in a remote village recently hit by the virus. The one he found most troubling was the man who asked repeatedly if he could catch Ebola through phone conversations with his cousin, who was quarantined. My friend explained transmission several different ways, emphasizing the impossibility of contagion through sound waves. Unconvinced, the man muttered that the Ministry did not know anything. The narrative of Ebola had transformed from something that could be banished with deliberate acts of human sociality into a malevolent force spread through sociality and, among other things, imported technologies and techniques whose power hinged on their invisibility. Simultaneous with this conversation, rumors emerged that the medical teams were bringing Ebola to remote villages and that Westerners were collaborating with powerful locals to create excuses to snatch the ill for use in cannibalistic rituals. Considering the medical teams who evacuated the sick wore PPE that hid their eyes, covered their skin, and rendered them alien-like, this reaction resonates with the trope of the dangers of the invisible.

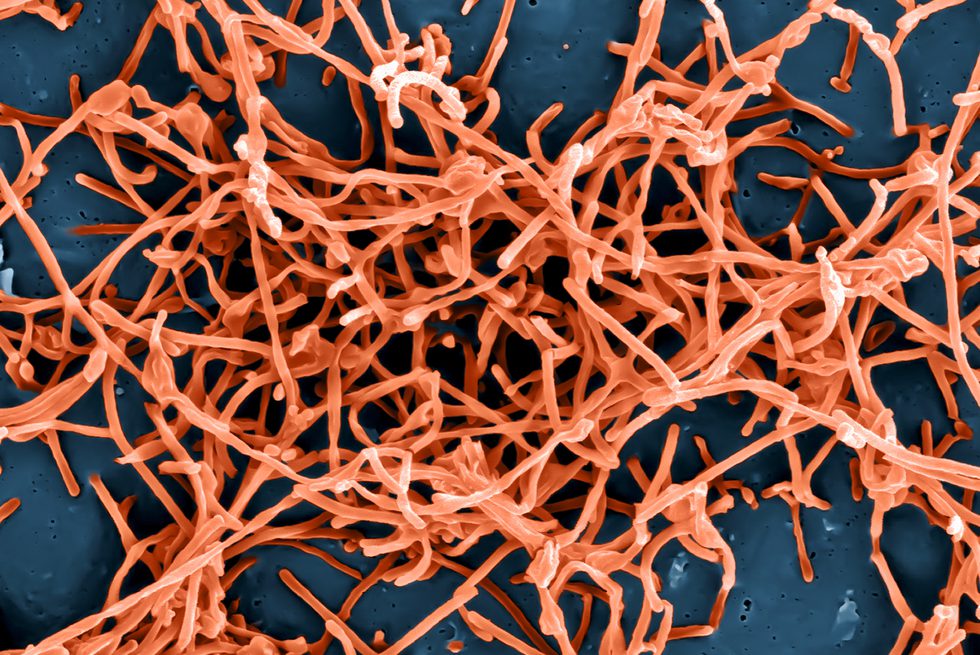

In Sierra Leone, people live communally, caring for family and social networks through the sharing of food, work, and the fostering of children. Witches, as antisocial consumers, are the antithesis of human beings. A witch’s power derives from the consumption of human flesh and human potential, implicating them in ritual killing and cannibalism. Unlike humans, witches in their human forms live alone and eat alone, and, most disturbingly, grow wealthy through unseen means. Their wealth is linked to a parallel invisible world that they inhabit at night, a “witch city” that is technologically advanced and dominated by many of the material items—such as cell phones—that are now implicated in the spread of an equally deadly, also invisible force. As Ebola education campaigns intensify, their message—no hugging, no handshakes, no caring for the ill, and no handling of the dead—creates clear linkages to the malevolent world of witchcraft. Ebola is a disease that destroys people’s ability to be human.

In the last two weeks, an even more disturbing set of rumors has emerged from the northern province, where I have worked for over a decade. In several towns where the WHO reported an upswing in Ebola deaths, text messages circulated that these deaths were not due to a virus but to the fact that multiple witch airplanes crashed into densely populated neighborhoods. All the witches onboard were killed, as well as some unlucky souls on the ground. According to my contact in the north, “This gives new meaning to the phrase ‘airborne transmission!’” She noted the resonance with a rising belief in the region that the illness spreads through airborne malevolent intent, from witch planes to witch guns, by which evildoers invisibly shoot their targets and cause imminent death. Interpreting Ebola in these terms means that the witches are now handling something that is so dangerous, so foul, it escapes their own ability to control and manipulate. Considering the number of health care professionals, including many foreigners, who have become infected and died from Ebola virus disease, these rumors illustrate witchcraft as potent commentary on the inability of the most powerful people to manage the forces of suffering and death. A witch plane crash is evil out of control, and so is Ebola.