Arts-based Pedagogy: More than a Creative Approach to Teaching

From the Series: Abolitionist Pedagogies

From the Series: Abolitionist Pedagogies

Art is more than the act of singing a song, drawing a picture, or writing a poem. It is a tool that unlocks the potential within. Researchers Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross in their book, Your Brain on Art, posit that the arts “improve our physiology by lowering stress-hormone response, enhancing immune function, and increasing cardiovascular reactivity. And that’s the beginning” (2023, 28). As important as the arts are to our well-being as working professionals and students, sadly, they have been taken out of public schools for lack of funding.

We must dismantle traditional modalities of learning and rebuild curriculum that enables students to exercise their creativity to demonstrate learning. Professors expect students to enter the academy prepared for the rigor of the college classroom. In those classrooms, traditional and non-traditional students are met with assessments like exams and quizzes. At the Pierre Laclede Honors College at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, where I teach, assessments take the form of essays and class discussion, which removes the barrier of exams. In either format, students are challenged with how to demonstrate their understanding of course material. This post affirms that arts-based pedagogy can help us teach in a manner that doesn't rely on penalizing but helps students understand nuance in safe and creative ways.

The University of Missouri–St. Louis, known colloquially in Missouri as UMSL, is considered a commuter school, as most students live off campus. Our students range from traditional students, beginning coursework immediately following high school, to students who return to college after starting families or serving in the military, and transfer students. According to data collected in the Fall of 2023, our total enrollment consisted of 14,787 students. Of that number, 58% identify as female, 41% as male, and 1% as non-binary. Regarding ethnicity, 40% of the student body on-campus belongs to minority groups, leaving much of the student population racialized as white (UMSL 2024).

Context matters when teaching sensitive subject matter. And as educators, we have a responsibility to our students not to penalize them for what they do not know. Yes, there are people, movements, and concepts we expect them to understand upon entering the academy, but many arrive unprepared. And to that end, we must prepare students by filling in the gaps with nuance. Perhaps the gap is filled with grace, or with leveraging student knowledge, and/or with guided arts-based instruction designed to achieve course objectives.

Regarding leveraging student knowledge, part of my teaching practice allows students to voice what they already know about a topic before we address the text. In my experience this small gesture builds confidence for students as demonstrated during class discussions. Quite literally, as students read articles in preparation for class discussions, I have them write and turn in class notes including: 1) up to three things they already know about the topic; 2) up to three things they learned; and 3) a question for class discussion.

This is especially helpful for those students who may have a fear of speaking in front of others. I allow all students the option to hand in their hand-written or typed notes for full participation points, while encouraging voices that have not been heard aloud to enter discourse as they feel comfortable. Lack of basic historical knowledge leads to students not participating in class discussions for fear of appearing incompetent among their peers. Peer to peer classroom affirmation is important for self-efficacy. Recognition from mentors and working with peers contributes to levels of confidence (Vasser-Elong et al. 2024).

Additionally, I reserve time and space for ‘silly questions’ during class time. I find that having that flexibility in class allows for student vulnerability about coursework, logistics, and other burning questions. This teaching strategy is abolitionist in its approach because it creates space that allows students to trust that their questions will not be met with ridicule or judgment. Above all, students bring their anxieties with them to the classroom and as stewards of their education, empathizing with them, human to human, will not only earn their trust but create safe spaces to learn.

While creating Allies, Spies, and Secret Friends, a course I designed to educate students on white allyship from chattel slavery, through the Jim Crow era, Civil Rights Movement, the Ferguson Uprising, and beyond, I was intentional about using poetry in the syllabus and other forms of art as teaching tools throughout the course. Sarah Browning’s “This is the Poem” appears at the top of my syllabus. Browning confronts her family’s role in chattel slavery (which is altogether different from other types of slavery mentioned throughout history) and helps students understand what to expect of the course.

I developed this course because I wanted students to understand how historical events inform the present. For example, how the relationship between American Slavery and the prison system both have roots in white supremacist ideologies. Moreover, that racism is about systems of oppression that marginalize whole groups of people. For example, one of my course objectives is for students to explain the ways in which humanistic and/or creative expression throughout the ages reflect the culture and values of its time and place. In using “This is the Poem,” we examine the era of slavery through the lens of someone with familial ties to that era in history and discover connections to current forms of injustices. While articles on the subject are used later in the course, the use of poetry allows for immediate interpretation. Poetry is written to enable the reader to access its content with fewer words. In addition, readers are invited into poetic content under the guise of art, and while artistic, poetry is also didactic in that readers also learn as they enjoy literature.

Art is at the center of my teaching practice, more specifically, the reading and interpretation of poetry and visual art. In my experience, students not only learn by using art but enjoy the process as well. I argue that using art in the classroom allows for varied modalities by which to channel emotions as learning occurs. Furthermore, arts integration is abolitionist because it creates space for holistic learning experiences where students can exhibit what they’ve learned.

There are a myriad of ways to use the arts as part of your instruction. For example, you could have students listen to classical music as they enter the classroom to set the tone. Or, while introducing a topic, you could use ekphrasis by having students write in response to visual art related to the session's content to get them engaged with the material. Students thrive in learning environments that offer assignments that are creative.

Having students illustrate their understanding creatively activates a part of the brain that promotes retention (Vasser-Elong et al. 2024). Using art in the classroom as a learning tool is an example of abolitionist pedagogy because it challenges the notion that traditional modes of assessment (i.e. written essays, exams, quizzes) work for all students. For example, one assignment I use is the photo essay.

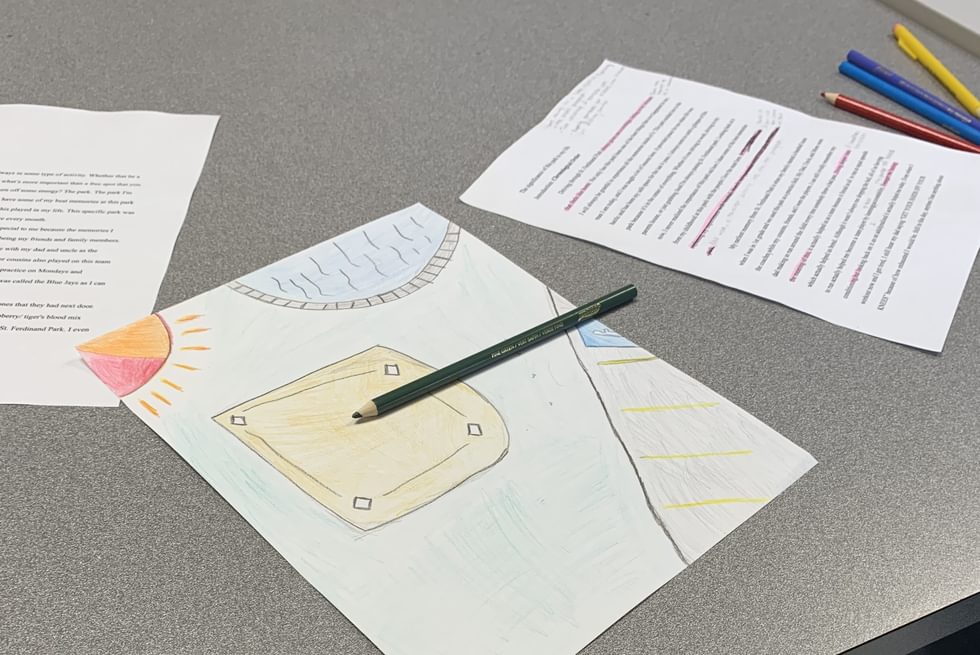

For my midterm assessment, students created photo essays and participated in gallery walks to view and comment on one another's works. The types of essays varied in scope. While some focused on the concept of allyship (see below) others were more specific in addressing sexism, colorism, xenophobia, and other forms of marginalization.

My course, Allies, Spies, and Secret Friends, delves into subject matter that may be traumatic for some students. So, while teaching and having in-depth conversations about race, it’s important for assignments to be didactic and creative to keep students intellectually stimulated. One way to do that is to allow time for students to process creatively. Below is an example of a photo essay from Spring 2024 illustrating a student’s interpretation of “Allyship” submitted as their midterm photo essay.

I acquired a panoply of magazines from a fellow artist in the community for the sole purpose of having students use them to create photo essays. Students were informed about the assignment at the beginning of the semester as we discussed the syllabus. In addition, we devoted class time leading up to midterm examinations with specific instructions.

Over the course of two ninety-minute class periods students cut images from the magazines and with glue sticks, arranged those images on eight by eleven-inch construction paper or eleven by fourteen-inch poster board. Students were also given the freedom to draw on their photo essays, using colored pencils, markers, and paint pens. Some students worked on their photo essays at home as well in-class, while others opted to only work their essays in class where they would access to all of the materials.

While the photo essays were powerful in their approach to illustrating themes discussed in the readings and lectures, it was delightful to watch students select and remove images from magazines. While listening to music in the background, the sound of paper tearing, the smell of paste, and the ambiance of students complimenting one another’s collage filled the room. I gave students the option to create a draft in-class to practice creating their finished products.

They were tasked with assembling a collage that spoke to a theme discussed in class (i.e. the intersection of indentured servitude and slavery; allyship; solidarity; colorism) and using the magazines, they selected images that supported their approach to those topics. The presentation part of this assignment included a gallery walk around the room to observe the other essays.

The day of the assessment, students taped their essays on the wall, and they each walked around the classroom to observe the photo essays. Next to each, students articulated what they felt the essay was about and as a class, we discussed the feelings that the essays drew to the surface. There was also time for students to verbally present their essay and answer questions from their peers.

This assignment was abolitionist in its approach to learning because where the traditional written essay accounts for grammar, syntax, and other grammatical structure, the photo essay ‘frees up’ the mind to illustrate ideas in ways that words cannot. Theoretically, art making has its own set of grammatical structure, syntax, and other criteria in professional settings. The setting for this assignment, however, was in contrast to the art studio of the professional artist, but rather of the classroom where the novice expresses themselves creatively. This is not to say that my students are not held accountable illustrating an understanding of the material, but for this assignment they were encouraged to express their ideas using art. In the course evaluations, students overwhelmingly expressed that they enjoyed the change of pace of creating photo essays for their midterm instead of a traditional essay.

While teaching content for Allies, Spies, and Secret Friends students learn about historical figures they may not have heard of before through what I call “character profiles.” Each week students learn about different historical figures and the complicated nature of their lives. Where applicable, I use poetry and visual art to provide nuance from articles and other materials.

My curriculum explains the ways in which humanistic and/or creative expression throughout the ages reflect the culture and values of its time and place. For example, through poetry, I introduce students to Sarah Moore Grimke and Angelina Grimke. Daughters of John and Mary Grimke, who owned enslaved people, the sisters grew up in opposition to their family’s view on slavery and as adults became abolitionists. Students also learn that while abolitionists, the Grimke sisters were also ostracized among their community for being outspoken women. Through class discussions, we compare this historical context to our present day and time. Among others, subjects that arise involve mass incarceration and the disparity in the number of African Americans to white Americans in the prison system.

Using the biography of the Grimke Sisters as a teaching tool allows students to ask questions. One of the most frequent questions that I receive throughout the semester is “Why am I just now, as a college student, learning about this?” And if time allows, we try and grapple with answering that and other questions that leave students frustrated for lack of knowing.

I am a practicing writer and visual artist, and while I use art as part of my teaching practice, I am intentional about sharing additional opportunities for students to learn. For example, I have a manuscript of poetry forthcoming entitled “Americanesque: a collectors guide to history,” and in it there is a poem “Women of their time” that captures a glimpse into the life of the Grimke sisters. This poem was on exhibit at the University of Missouri–St. Louis as part of Turn Upon Them: Reveal to Heal exhibit, an artistic expression of injustice, healing, and communal outreach. Students received extra credit for attending the exhibit.

Women of their Time

Sarah & Angelina

raised in the cradle of slavery,

picked cotton, shelled corn.

Were outspoken,

in South Carolina

where they were born.

Outcasts on both sides

of the Mason Dixon,

when women

couldn’t speak their minds.

Using poetry like Sarah Browning’s “This is the Poem” and other culturally relevant tools helps students identify the relationships among ideas, text, and/or creative works and their cultural and historical contexts.

As educators, we have opportunities through our course development to dismantle systems of oppression that stifle creativity and negatively impact student learning. Abolitionist pedagogy is not about making coursework easier. To the contrary, it is about challenging students to think critically while facilitating their learning in modalities that keep them engaged. Why not make learning fun and in so doing, center voices that have for far too long been marginalized? Doing this work, being intentional about disrupting narratives with nuance and creativity, helps to frame a comparative context to critically assess the ideas, forces, and values that have created the modern world.

Browning, Sarah. 2015. “This is the Poem.” Vox Populi.

Magsamen, Susan, and Ivy Ross. 2023. Your Brian on Art: How the Arts Transform Us. New York City: Penguin Random House.

University of Missouri–St. Louis. 2023. “UMSL By the Numbers.” Accessed October 19, 2024.

Vasser-Elong, Jason. 2024. “Women of their Time.” Turn Upon Them: Reveal to Heal (exhibit). Curated by Allena Brazier at the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

Vasser-Elong, Jason, Jane Kelley, Kira Carter, and RC Patterson. 2024. “STEMinism: Analyzing Factors that Improve Retention of Women in STEM.” Ed.D. Co-authored diss., University of Missouri–St. Louis.