This post builds on the research article “Attuning to the Chemosphere: Domestic Formaldehyde, Bodily Reasoning, and the Chemical Sublime,” which was published in the August 2015 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editorial Footnotes

Cultural Anthropology has published numerous articles on the body and embodiment, including Thomas Csordas’ seminal article “Somatic Modes of Attention” (1993), Kathleen Stewart’s “Nostalgia—A Polemic” (1998), and Elysée Nouvet’s “Some Carry On, Some Stay in Bed: (In)convenient Affects and Agency in Neoliberal Nicaragua” (2014). See also the Curated Collection on Affect, Embodiment, and Sense Perception and the Field Notes series on Affect.

Additionally, Cultural Anthropology has published articles on scientific practices and ways of knowing, including Kim Fortun’s “Ethnography in Late Industrialism” (2012) and Carlo Caduff’s “Ethnographies of Science: Conversation with the Authors and Commentary” (1999). See also the Field Notes series on Studying Unformed Objects.

About the Author

Nicholas Shapiro is a Matter, Materials, and Culture Fellow at the Chemical Heritage Foundation and an Open Air Fellow at Public Lab. He completed his doctorate at the University of Oxford in 2014. His work on the chemicals that hold together and corrode late industrial worlds moves between the social sciences, the natural sciences, and the arts.

Interview with Nicholas Shapiro

Julia Sizek and Ned Dostaler: How did you become interested in the topic of domestic formaldehyde exposure?

Nicholas Shapiro: Like many doctoral projects, I came to the topic by a combination of happenstance, hunches, and longstanding interests. The project started in post-Katrina New Orleans, where I knew I wanted to work on chronic health issues. A friend was working on the massive lawsuit related to formaldehyde exposure endured by Gulf Coast residents in trailers supplied by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). At the same time, I was in conversation with Kim and Mike Fortun and their collaborators about The Asthma Files. Asthma was one of the primary claimed harms as a result of formaldehyde exposure in FEMA trailers, and New Orleans had a unique history of asthma epidemics. So my project grew out of this connection and, over the course of two years of fieldwork, it burgeoned out from the Gulf Coast, tracking the quasi-legal resale of these contaminated homes, mapping their distribution, speaking with new residents, and testing the air quality of these homes. The FEMA trailers are just one eventful instance of corrosive encounters with formaldehyde that are occurring in homes across the United States and that are increasing in many industrializing nations. In this article, I sideline the specifics of how I started becoming attuned to the chemosphere in the hope of talking about larger infrastructures, molecular encounters, sensations, and embodied labor practices that transcend my personal inroads into the subject.

JS and ND: Your article begins with a comment on the ubiquity of formaldehyde, and your own research included fieldwork in twelve states. How do you consider bounding your research object, both as a practical matter and as a concern for the theory you would produce?

NS: On one hand, my research object is obscenely bound: a single compound composed of just three elements. On the other, my work is wildly spiraling as formaldehyde is everywhere: it’s in me, it's in you, my desk is held together by it and at least 20% of the energy production that is keeping my computer on right now is chugging it out into the troposphere (the lower slice of atmosphere from which we pull our breath). But its distribution is neither even nor benign. Apprehending where this chemical takes hold, why, and to what effect was crucial to my project. Letting myself be pulled into the multitude of worlds that the chemical holds together was the only method I thought could rise to the task of tracking not a complete object but a widespread ingredient, as well as the industrial practices that saturate our building materials in it, the supply chains that circulate the commodities into which it is embedded, and the tools used to apprehend its fugitive presence. Impractical? Without a doubt, but ethnography often is and I’m not sure I would have been able to glean and assemble minute scientific practices with unsanctioned tools (i.e., bodies) if I hadn’t shaken my dependence on eventfulness. I moved beyond looking at a place-based issue after a globally recognized event (Katrina) to investigating a constellation of linked spaces, things, and happenings.

On a theoretical level, the wide-ranging pursuit of formaldehyde also strengthened my justice claim. It could have been a project about the bungled federal housing response to Katrina and and the equally bungled legal attempts at recompense, but instead it is a much larger and more systematic effort to comprehend the making and unmaking of the vessels of exposure we call home. The larger project is about the double binds of late industrialism, the distribution of capital and housing crises that enable exposure, how endogenous formaldehyde in our bodies (just like industrial formaldehyde in our homes) is neither strictly physiological nor pathological, and so on. Overall, I think, or at least hope, that my methods did keep open multiple scales, expertises, and experiential strata to give me the empirical grounds to make more interesting claims about how the world works.

JS and ND: You allude to the chemical sublime as a way to access a grander “event” through continued accumulation of what you call “minor enfeebling encounters.” This differs greatly from the traditional idea of the sublime—how did you come to consider these mundane events as a sublime object of study?

NS: There are two strands to the genealogy of the chemical sublime. One is empirical; we live in insidious times. Attritional encounters speckle our everyday. People don’t need to know the term “structural violence” to know that the forces that are enabling their existence are simultaneously, ever so slowly smothering them. It is not so much that I found these mundane molecular dramas sublime on my own accord but that I am relaying this sense from the people whom I met. It’s not hard to imagine how staggering it must be to scale up from low-velocity, diffuse, and intimate chemical encounters to the substructure of almost all of the built environment for the past half century. So in some sense, the chemical sublime does share attributes of both Immanuel Kant’s “mathematical” and “dynamical” sublime, which relate to the trembling apprehension of unfathomable scales and fear of massive geological or climatic events (earthquakes, hurricanes, etc.) viewed at a distance. But those still-prevailing notions of the sublime didn’t do the work I needed them to do, as they are rife with assumptions about the relations of the sensible and the supersensible, what forms can conjure fearfulness, and how such feelings are resolved or not. While I can’t really speak to whether Kant’s notions are outdated or whether they never held water to begin with, they were more hindrance than help in making sense of the worlds I moved through. The rejiggering I did in conceptualizing the sublime can hopefully encourage alternative ways of making caustic happenings count under current configurations of capital, materials, and dreams of the good life.

The specific way it was theorized emerged from reading, rereading and re-rereading Joseph Masco’s article on nuclear technoaesthetics. The differences between the technical systems we study (nuclear detonations and domestic off-gassing, respectively) helped me articulate why we need an alternative inroad into the sublime and what it might be useful for.

JS and ND: You note that your own experiences in the field came to be mediated through formaldehyde as you became attuned to the substance. When did your chemical attunement become an essential part of your study, and how did you come to this angle of approach?

NS: I’m not sure if my own chemical attunement was an essential part of the study. I certainly thought so for a while, and was really excited by the idea that I was bearing witness with my own minor harm. “If I literally embody the detriment I make my living studying,” I probably thought on some level, “can I feel less exploitative?” But then a colleague, Alex Nading, very helpfully pressed me on the point and I came to see radical empiricism in this context to be a bit self-indulgent and not an especially strong index of the costs of exposure experienced by my informants. In my article, I try to set up my own experiences as supportive of the claims of my informants while also dismissing my own exposures as too diminutive and privileged to be indicative of what it would be like to be stuck in a toxic home with no financial possibility of leaving. I’m sure that my own irritations after a short exposure was part of what kept me agitated and thinking about formaldehyde every day for the past six years. In that sense, it probably was essential at an ancillary, motivational level, and perhaps it adds a level of trust to my informants’ accounts as audiences for my work invariably insinuate that my informants are faking it.

JS and ND: What’s next in your research?

NS: Over the last year and a half, I have been working with a nonprofit called Public Lab that develops open-source and low-cost environmental monitoring tools. In many ways, the work that I’ve been doing with collaborators at Public Lab are experiments in validating the chemically attuned body and finding ways to aggregate subclinical symptoms across space—in other words, how to mobilize the chemical sublime. To do that, our team includes an epidemiologist (Nicole Novak), a web designer and programmer (Jeff Warren), an environmental chemist (Gretchen Gehrke), and an industrial designer (Mathew Lippincott), among others.

As part of a project called Where We Breathe (I know, it’s a little new-agey sounding), we are building a web platform that enables people to register their health impacts in an epidemiologically validated survey, view and analyze aggregate anonymized data, share experiences and mitigation techniques, correlate their symptoms to low-cost formaldehyde test results, and organize with people who are facing exposures from the same infrastructures (or are within the same legal jurisdiction). We are developing a lending library of low-cost formaldehyde meters and are testing a system for pulling air through the root systems of common houseplants to scrub formaldehyde from the air—I mention this metabolic function of plant rhizospheres briefly in the article. An overview of this work is available here. I view this applied work as a way to make good on my ethical obligations to informants, practice my critique of science and larger organizing schema, and plunge deeper into the systems I study. But such endeavors are not without risk and we have to keep in mind that by performing functions that the state and science jettison or avoid, we could be hardening current biopolitical regimes rather than creating new ways of being.

I’m working on cramming all of this into a book. With Jody Roberts and Nasser Zakariya (who I accidentally left out of the article’s acknowledgments—eek!), I’m also beginning to think about what chemistry can teach us about materiality that models based on physics and biology can’t. And, well, a few other fun things.

Multimedia

The Scale of It All

First stop: the European trade organization for the formaldehyde industry has an interactive graphic that demonstrates the prevalence of formaldehyde in the home.

Technical Means of Apprehending Your Air

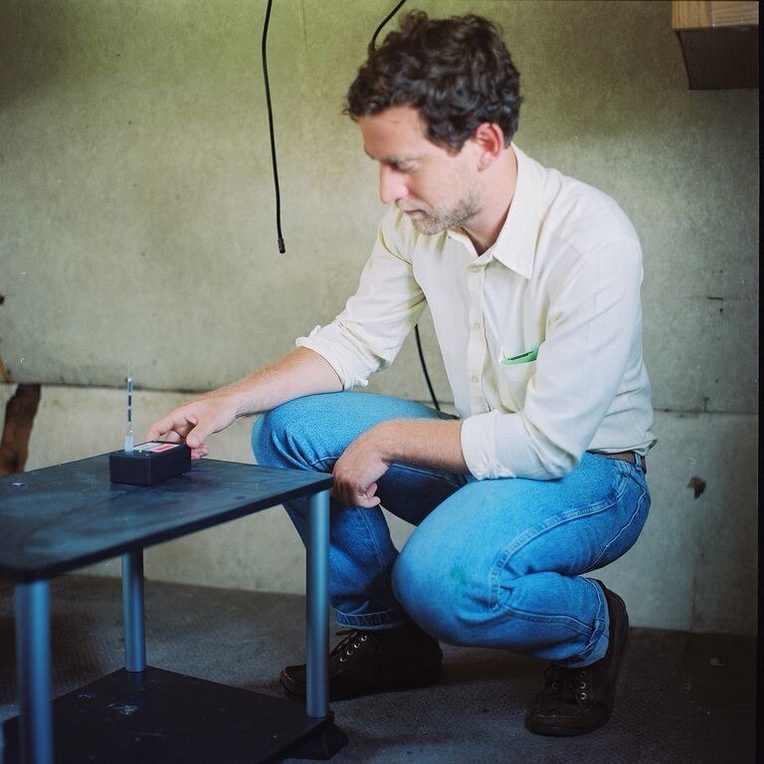

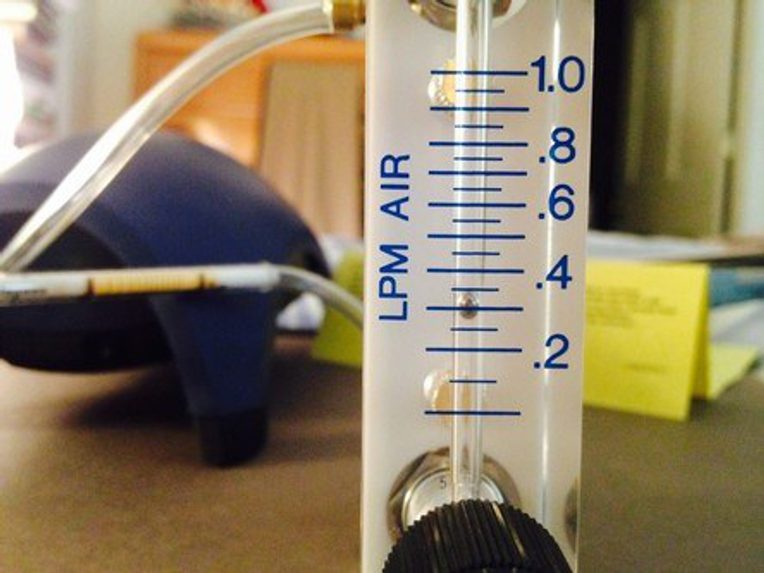

Wondering how to test your home, if you're curious about its formaldehyde levels and don’t think you are a human Geiger counter? In 2014, Nicholas Shapiro developed a set of instructions on how to build your own low-cost formaldehyde meter.

This aquarium pump, which gets repurposed as a vacuum, pulls air through a flow meter to regulate how much air passes through a tube that changes color when it contacts formaldehyde. After thirty minutes of pulling air, indoor formaldehyde levels can be read like a thermometer.

A Hat Tip to Consumerist Irony

Nick’s Public Lab collaborator, Mathew, has developed a lending kit that utilizes the same technique of formaldehyde detection described above. Public Lab will soon be offering these kits at publiclab.org. You can make the kit yourself using copyleft instructions, borrow a kit, or buy your own preassembled kit. Here is a video of Mathew testing Public Lab’s DIY Formaldehyde Testing kit.

Related and Resonant Readings

On the Sublime

Frierson, Patrick, and Paul Guyer, eds. 2011. Kant: Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime and Other Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kant, Immanuel. 1987. The Critique of Judgment. Translated by Werner S. Pluhar. Indianapolis: Hackett. Originally published in 1790.

Masco, Joseph. 2006. The Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post-Cold War New Mexico. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Žižek, Slavoj. 1989. The Sublime Object of Ideology. London: Verso.

On Atmosphere and the Effects of Breathing

Choy, Timothy. 2012. Ecologies of Comparison: An Ethnography of Endangerment in Hong Kong. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Masco, Joseph. 2010. “Bad Weather: On Planetary Crisis.” Social Studies of Science 40, no. 1: 7–40.

Mitman, Gregg. 2007. Breathing Space: How Allergies Shape Our Lives and Landscapes. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Petryna, Adriana. 2013. Life Exposed: Biological Citizens after Chernobyl. 2nd edition. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Sloterdijk, Peter. 2009. Terror from the Air. Translated by Amy Patton and Steve Corcoran. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e). First published in 2002.

Waldman, Linda. 2012. The Politics of Asbestos: Understandings of Risk, Disease and Protest. London: Routledge.