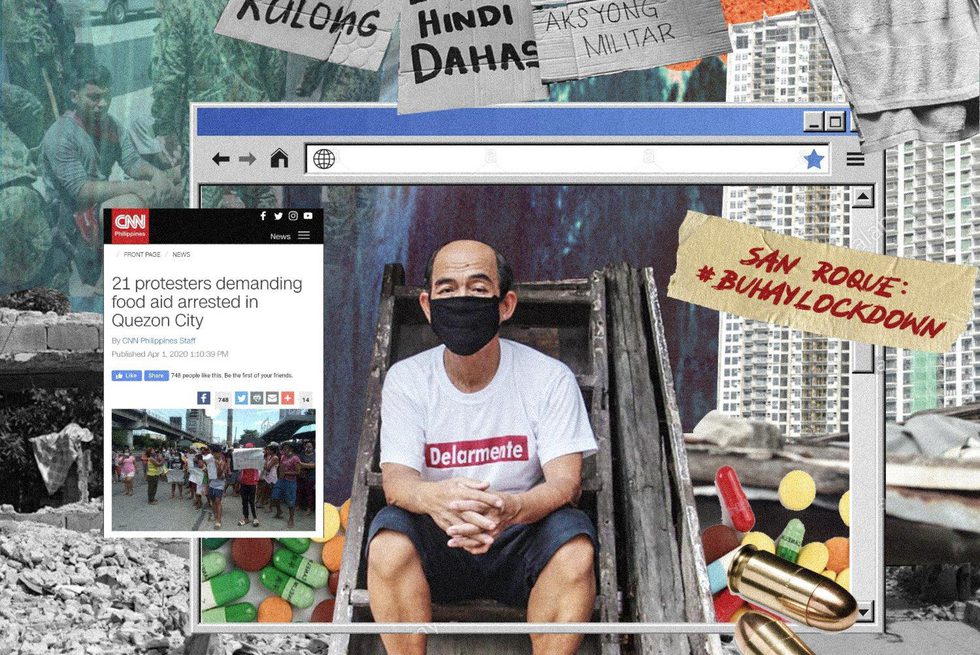

Fifteen days after Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte ordered a Luzon-wide “enhanced community quarantine” to curb the spread of Covid-19, the residents of Sitio San Roque in Quezon City took to the streets to demand food and aid after their livelihood and employment were disrupted by the lockdown. Their rallying call “Bigas hindi bala [rice, not violence]” is a public clamor about the government’s slow response in providing social safety nets. San Roque residents are low-wage workers, mostly in factory and construction (both undervalued labor in the country). While their lives had been precarious even before the community quarantine was enforced, they have become more vulnerable as they face an additional threat to their lives.

Covid-19 has magnified dahas (violence) in the Philippines. For one, instead of providing relief to San Roque residents, the local government responded by arresting twenty-one protesters. Dahas is not new to the people of San Roque and, in general, the poor of the Philippines. They have experienced all forms of violence through the state’s consistent and deliberate disregard for their rights.

Achille Mbembe (2003) emphasizes that states allow some people to live and some people to die. This is definitely true in the case of the Philippines. Poverty has plagued the nation for a long time, which has resulted in the unnecessary and preventable deaths of those who are “allowed to die.” Many poor Filipinos are literally allowed to die, whether through deaths from extrajudicial killings (which disproportionately target the poor) or from slow deaths because of poverty, hunger, and disease. Meanwhile, the elites are largely protected from harm.

The Covid-19 situation pushed President Duterte to enact an “enhanced community quarantine,” which entailed restrictions on movement and closure of public transportation and establishments that are not concerned with food distribution. Penalties were also imposed for those who violate the recent law that was drafted to control and manage the disease. However, this law barely emphasizes providing medical solutions.

Covid-19 seems to cut across classes as it also infects those who are powerful. However, it does not occur on equal terrain. In recent months, “everyday violence”—banal, routine suffering and death (Scheper-Hughes 1992)—affecting Filipino lives has gone from bad to worse. The Covid-19 pandemic has put into stark relief multiple barriers in the lives of the poor. With the restrictions in movement, the informal economy has taken a significant hit, making thousands of Filipinos unable to work. With no work comes no food. This is especially true for Filipinos who live hand-to-mouth. Hence, many Filipinos are currently saying that if they don’t die of Covid-19, they will die of hunger. Furthermore, many of the poor live in slums with no access to clean water, which makes social distancing and proper hygiene impossible.

These deeply rooted inequalities are attributed to the oppressive structures and oligarchies that have been solidified since the Spanish colonization. These are further concretized by the neoliberal project that has occurred in the nation since the 1970s due to pressures from Bretton Woods institutions. Together, they constitute what Johan Galtung (1969) calls “structural violence,” the systemic inequalities that lead to otherwise avoidable suffering and death.

The neoliberal project in the Philippines resulted in the rolling back of the state from its responsibilities to provide welfare for its people. It has promoted labor export policies, which intensified the mass exodus of workers; labor flexibilization through contractualization of labor; and the reduction of budgets for social services. These policies have resulted in the further entrenchment of poverty and precariousness in the lives of Filipinos. Precariousness is dangerous as it makes people more vulnerable to the violent conditions amplified by Covid-19.

Certainly, the neoliberal project has remained in Duterte’s administration, which has actively colluded with China through loans and agreements. Its tiptoeing, for fear of China’s retribution, resulted in the spread of the disease in the country as it failed to swiftly order travel bans and quarantining of flights coming from China. Meanwhile, the health budget remains below the World Health Organization’s recommended allocation. There are only a few government hospitals that can cater to the vulnerable. When the government hospitals were turned into exclusive Covid-19 centers, the only access to healthcare for indigent patients was brutally cut off.

Despite the Duterte administration’s Universal Health Care Act, healthcare remains largely privatized as the law simply widens the breadth of the national insurance scheme that will benefit private hospitals. Healthcare remains not free. While the administration had promised free testing and healthcare for positive patients, it recently announced that it will start putting a cap on its coverage of the patients’ fees beginning April 14, 2020. Those who are the most vulnerable have always been unable to afford hospitalization costs. What more if they acquire Covid-19?

Furthermore, low wages, together with labor export policies, have had the specific effect of pushing healthcare workers to look for greener pasture abroad. Hence, there is now a shortage of nurses and doctors within the country. This is alarming as the number of doctors and nurses who have remained is slowly dwindling as they succumb to Covid-19. The state, in fact, has allowed them to die because the protection and tests that should have been given to them did not manifest. Here, too, structural violence is present. The deaths could have been avoided had they been given proper protective equipment.

Dahas, in the form of structural violence and everyday violence, remains in full throttle in the midst of Covid-19. The oppressive structures in place have been legitimized by the state through oppressive neoliberal policies and disregard for human rights in the midst of the pandemic. Covid-19 did not create structural violence, but its presence exposes the present conditions and the everyday violence that people experience.

References

Galtung, Johan. 1969. “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research.” Journal of Peace Research 6, no. 3: 167–91.

Mbembe, Achille. 2003. “Necropolitics.” Translated by Libby Meintjes. Public Culture 15, no. 1: 11–40.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy. 1992. Death without Weeping: The Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil. Berkeley: University of California Press.