This post builds on the research article “You-Will-Kill-Me-Beans: Taste and the Politics of Necessity in Humanitarian Aid,” which was published in the August 2016 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Micah M. Trapp is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Memphis. Using Trapp’s article as a jumping-off point, this Teaching Tools post addresses the relationship between food, reason, and taste in the context of a Liberian refugee camp and in Memphis, where Trapp’s current research uses school lunch meals as a case study to explore how the distribution of food resources and entitlements intersect with notions of care.

The Cultural Anthropology website is a resource for other food-related content, including a 2013 Field Notes series on food.

Interview

Julia Sizek: What inspired you to write this article, and how does this article relate to your broader research interests?

Micah M. Trapp: As a researcher, I’ve always been interested in how we filter information through all of our senses. My initial research design focused on household food security at the Buduburam camp, but when I noticed that my field notes were riddled with intense sensory descriptions of the food and eating, I realized that existing notions of food security did not adequately account for the experiences of food aid. Taste suddenly emerged as an important methodological and theoretical aspect of my research.

I’ve also wanted to find a way to write about the innovative and sharp ways that Liberians think about and experience food. You-will-kill-me-beans and drip are exemplary expressions of the ways in which Liberians focused a critical eye on global inequalities, while maintaining a sense of humor. This work has also compelled me to think about the significance of taste in other contexts of aid. For example, in my new research on school lunch meals, I am interested in exploring how taste shapes the experience and impact of food entitlements. School meals are notoriously stigmatized as disgusting, but how do what I call the tastes of necessity help us to understand the underlying social dynamics of poverty, inequality, and the right to food? Can attention to taste help us to create more humane feeding programs?

JS: What would you want to highlight in a lesson on food aid for undergraduates? What would you want them to understand after that lesson?

MMT: It can be really hard for students (and practitioners) to think critically about doing good, especially if they have never been on the receiving end of charitable assistance. Students are often driven to think about making the world a better place, but in order to create change students need to be critical thinkers. One of the points I would want to make in a lesson about food aid is that intentions do not always ensure outcomes. Theoretically, the distribution of food aid resources is a good thing, but by looking at the experience—the taste—of eating corn-soy meal, for example, we can start to ask questions about the impact of food aid. Is the distribution of food the best approach to addressing inequality? As humans, we can all identify with the experience of being disgusted, so how do the sensory experiences of taste provide an avenue for thinking about humanity?

Suggested Learning Goals

After this lesson, students should be able to:

- Identify the logic of humanitarian aid and its relationship to the tastes of necessity

- Define biography of taste and apply the concept to new examples

- Discuss how food relates to humanitarian aid

Activity: Calorie Counting

In this article, Trapp discusses how foods were evaluated in terms of sensory pleasure rather than nutrition, which was understood as what is biologically necessary to sustain life. Anthropologists have long related food to its cultural importance and critiqued the humanitarian rationalism implied by food provision in refugee camps, as seen in Margaret Mead’s (1943) discussion of the provision of food to Germany after World War II. In this activity, we will assess the nutritional quality of the food aid discussed in Trapp’s article and consider how measurements of food have changed over time, using data from actual food aid programs in 1947 and today. Here's a link to the charts you'll need.

Reflection Questions

- Comparing the charts, how have categories used for assessing food quality changed over time? Why do you think they have changed?

- Comparing the charts, which vitamins are prioritized and why do you think they are prioritized?

- How have approaches to food aid changed over time? How would you compare the suggestions and critiques offered by Margaret Mead to Micah Trapp’s critique? (For example, compare Mead’s discussion of white flour to Trapp’s discussion of corn and soy products.)

- How would you apply Mead and Trapp’s arguments to the “German Agricultural and Food Requirements” report?

Suggested Readings

Grossman, Atina. 2011. “Grams, Calories, and Food: Languages of Victimization, Entitlement, and Human Rights in Occupied Germany, 1945–1949.” Central European History 44, no. 1: 118–48.

Mead, Margaret. 1943. “Food and Feeding in Occupied Territory.” Public Opinion Quarterly 7, no. 4: 618–28.

Activity: A Biography of Taste

Using the biographies of taste provided in Trapp’s article (ugly rice, drip, and you-will-kill-me-beans) as examples, create your own biography of taste using a food of your choice.

Helpful hints and guiding questions:

- What makes a biography of taste different from a biography of a commodity?

- How do biographies of taste change what Trapp calls “the distribution of the sensible”?

- How do these biographies of taste counter what Trapp calls the “biopolitical politics of necessity”? What are the politics of the biography of taste?

Suggested Readings

Appadurai, Arjun. 1986. “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 3–63. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Highmore, Ben. 2008. “Alimentary Agents: Food, Cultural Theory and Multiculturalism.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 29, no. 4: 381–98.

Mintz, Sidney W. 1985. “Power” and “Eating and Being.” In Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History, 151–214. New York: Penguin.

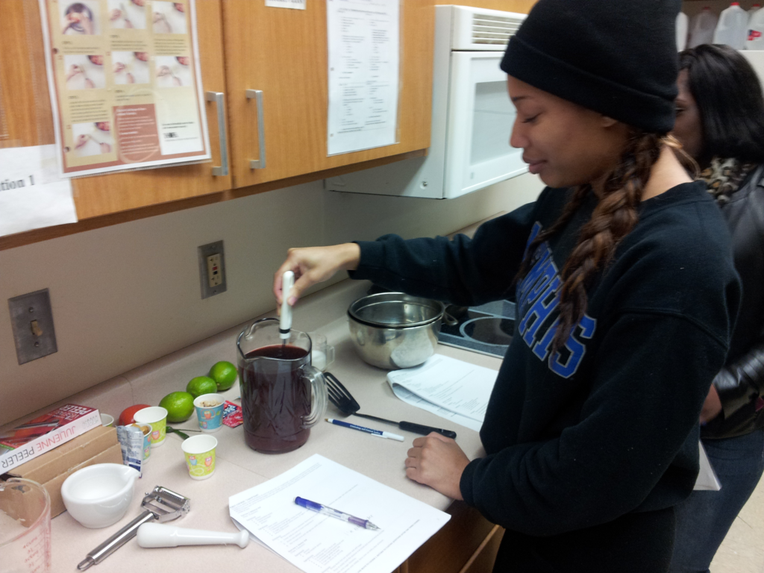

Activity: Recipes for Aid

This activity has been adapted from one of Trapp’s courses at the University of Memphis. It has been designed to help students explore and analyze embodied culinary knowledge, creolization processes, and connections between meaning, use, and status of foods. The first recipe, Hibiscus Aid, can be prepared in about ten minutes, while the second recipe, Ghetto Aid, can be prepared in about five minutes.

Exercise 1: Hibiscus Aid

Equipment:

- pitcher

- long-handled spoon

- small saucepan

- stovetop

- strainer

Ingredients:

- 1 quart water

- ¼ cup hibiscus blossoms

- 1 tablespoon fresh ginger, finely chopped

- ½ cup sugar (granulated white, honey, or agave; your choice)

- Juice of half a lime

Directions:

- Bring water to boil in saucepan. Remove from heat and add ginger, hibiscus, and sugar. Stir until sugar dissolves.

- Cover and let cool to room temperature.

- Strain into pitcher.

- Stir in lime juice and refrigerate until chilled. Serve cold.

Exercise 2: Ghetto Aid

Equipment:

- pitcher

- long-handled spoon

Ingredients:

- 2-3 quarts water

- ½ envelope cherry Kool-Aid

- ½ envelope tropical punch Kool-Aid

- ½ envelope grape Kool-Aid

- 2 cups sugar, or to taste

- Lemon slices, for serving

Directions:

- Empty Kool-Aid into pitcher and add sugar.

- Pour in water until the mixture is as sweet and concentrated as you like.

- Stir until sugar dissolves.

- Refrigerate until chilled. Serve over ice with a slice of lemon.

Tasting and Reflection Questions

- Which type of “aid” did you prefer and why? How would you relate your aid preferences to Pierre Bourdieu’s (1984) discussion of taste and social class?

- Drawing upon Sidney Mintz’s (1985) characterizations of sugar use, how is sugar used in Ghetto Aid and Hibiscus Aid? Is it the same for each? Why or why not?

- In his chapter on liquid soul, Adrian Miller (2013) talks about the importance of red beverages and draws a historical connection between bissap and Kool-Aid. Do you think Kool-Aid is a creolized version of bissap? In your response, compare Miller’s conclusions about the connections between the two beverages and Judith Carney’s (2001) analysis of Black rice.

Suggested Readings

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Selections from “The Habitus and the Space of Life-Styles,” “The Choice of the Necessary,” and “Conclusion: Classes and Classification.” In Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, 175–208, 372–96, 466–84. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Carney, Judith A. 2001. “Rice Origins and Indigenous Knowledge” and “Out of Africa: Rice Culture and African Continuities.” In Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas, 31–105. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Miller, Adrian E. 2013. “What is Soul Food?” and “What’s Sweet, Red, and Drunk from a Jelly Jar? Hint: Liquid Soul!” In Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine One Plate at a Time, 1–10, 222–39. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Mintz, Sidney W. 1985. “Consumption” and “Power.” In Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History, 74–186. New York: Penguin.