Covid-19 has ushered in a new grammar of intimacy. Every physical interaction inspires a calculation of risk management. Consequential decisions are made over the essentiality of a person, a service, or a product. What happens to the essence of care work during a pandemic?

Amid the current preoccupation over appropriate closeness, babies continue to be born. I am a birth doula and doctoral student in New York City, the current epicenter of the global outbreak. As the seriousness of the outbreak was absorbed by the city, and restaurants, cultural institutions, and the largest public school system in the country shut down, two major hospital systems barred laboring patients from having any support people while giving birth. This decision went against New York State’s Department of Health and the World Health Organization, both of whom established that one support person was essential to the care of the pregnant patient. We birth workers quickly organized and petitioned for the rule to be overturned; six days later, Governor Andrew Cuomo issued an executive order that required hospitals to allow a support person during labor and delivery. The rapid efficacy of this virtual activism floored me. I have been working as a doula for over ten years and I know that advocating for institutional change from a position of marginality has always been challenging. At a time when patients who are gravely sick with Covid-19 must face the prospect of dying alone, it was all the more striking that the prospect of birthing alone prompted such swift response.

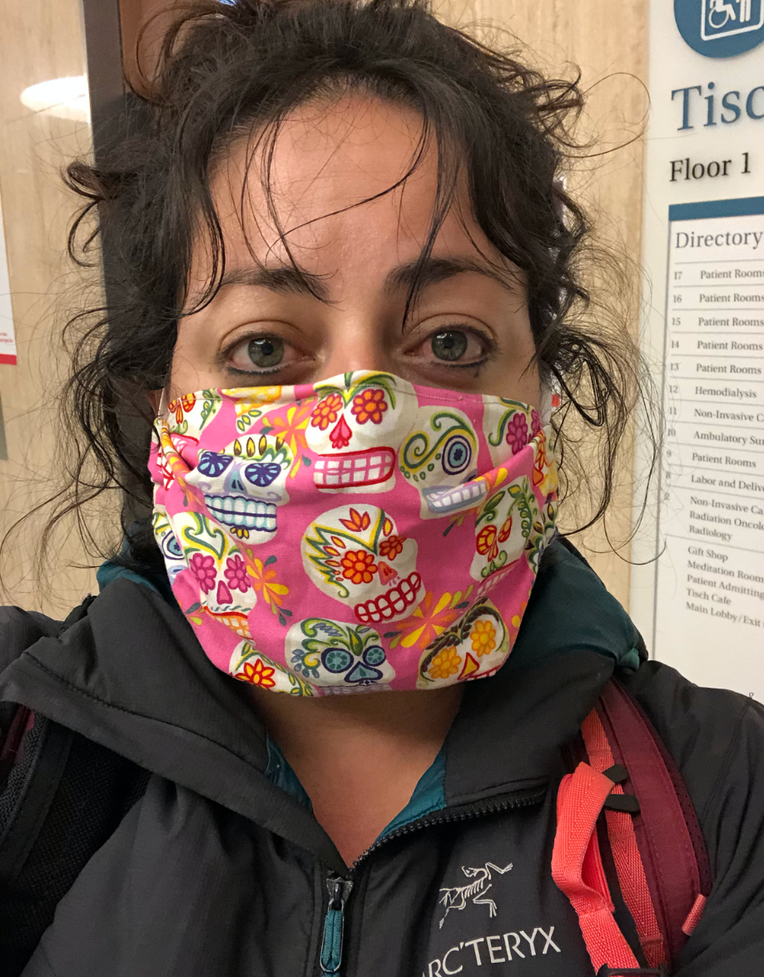

While I was socially distancing at home, conducting prenatal meetings with clients via Zoom and helping babies breastfeed over FaceTime, one of my clients—a white woman and single mother by choice—checked into the hospital to have her labor induced. Since hospitals were now allowing one support person, I prepared to leave my neighborhood for the first time in over three weeks. My colleague made me a fabric mask that I put on as soon as I got into the Uber and did not take off for over twenty-four hours.

In the hospital lobby a nurse took my temperature: 98.6 degrees. A sigh of relief. But then the security guard next to her said, “Doulas are not allowed anymore.” After I clarified that my client did not have a partner and that I was her “plus one” she gave me a pass and I made my way upstairs. The halls were empty. A doctor slept on an armchair, crumpled up like a wad of paper. Outside of my client’s room, a bulletin board extending from floor to ceiling was filled with about thirty paper bags with names written on them. Later I confirmed with a nurse that the bags held N95 masks that were being reused by the staff. “We only get one,” she said.

Birth work is physically intimate. I massage laboring bodies, breathe with clients through contractions, and wipe up bloody mucus and feces. Sweat, tears, and amniotic fluid often find their way onto my clothes, my hands, my hair. Birth work is also emotional labor. I spend hours looking into my clients’ eyes—using my entire face to comfort and encourage them through the intensity of their experience. Wearing a mask that extended from the bottom of my eyes down to my neck limited my ability to express nuance and affect, qualities that are central to birth support. I kept apologizing to my client for wearing the mask, “I’m sorry that I have to do this, it’s to protect you” (but I dared not take it off, knowing it might also protect me). She kept asking, “What?” when she did not understand my muffled sounds or if my eyes did not express my thoughts clearly enough. The moments of connection came through like morse code—in dots and dashes.

Her labor progressed slowly and her temperature began to rise. 99, 99.5, 99.8. Finally, the three-digit threshold was crossed: 100. The nurse came and informed us that the new protocol, created that day, meant that my client now needed to be tested to rule out a Covid-19 infection. She was, from that moment forward, a “person under investigation (PUI).” Two nurses came in, wearing head-to-toe PPE, something I had never before seen on labor and delivery. They inserted a very long swab into her nose. I held my client’s hand as she reacted to the depth of the probe.

Soon after the test, my client began to vomit. Vomiting is a sign of progress. It signals that the body is close to delivering the baby—the uterus expels everything in its way. It is also a form of what Talal Asad (2003, 88) calls agentive pain, “integral to an activity that reproduces and sustains human relationships.” She vomits and I respond. I pull back her hair, grab a bucket, wipe her mouth. But her status as a PUI registers within my body. I find myself leaning back, ever so slightly; possibly an imperceptible shift to her but a palpable one to myself.

Her baby was born and placed on her chest, just as she had wanted all along. But he was also a PUI. The suspicion inherited at birth, a congenital condition—until a test would eventually clear him. Weeks later, a client who experienced mild symptoms before her scheduled Cesarean birth shared that the term PUI made her “feel like a criminal.” When she tested positive for Covid-19, she was made to birth alone and treated as a threat to her newborn. After the birth she remarked upon the unique trauma of simultaneously feeling like a victim and a perpetrator.

These experiences of birthing under investigation—of feeling like a criminal or a threat—are not novel. Black and brown bodies have long endured harrowing inequity throughout the reproductive cycle (Roberts 1997; Chavez 2017; Cooper Owens 2017). But Covid-19 has widened the scope of who is isolated, surveilled, made to feel suspect, and treated as dangerous in maternity wards. As the consequences of the pandemic begin to emerge, I wonder what the awareness of losing certain privileges can generate. Might temporary access to embodied experiences of discrimination inspire and help mobilize systemic change, beyond individual feelings of empathy and outrage?

References

Asad, Talal. 2003. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, and Modernity. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Chavez, Leo R. 2017. Anchor Babies and the Challenge of Birthright Citizenship. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Cooper Owens, Deirdre. 2017. Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Roberts, Dorothy. 1997. Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty. New York: Vintage.