This post builds on the research article “Bread, Freedom, Social Justice: The Egyptian Uprising and a Sufi Khidma,” which was published in the February 2014 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editorial Footnote

Cultural Anthropology has published a number articles on the temporalities of care, humanitarianism, and philanthropy including Clara Han’s “Symptoms of Another Life: Time, Possibility, and Domestic Relations in Chile’s Credit Economy” (2011), Erica Bornstein’s “The Impulse of Philanthropy” (2009), and Peter Redfield’s “Doctors, Borders, and Life in Crisis” (2005).

Cultural Anthropology has published articles about Sufi Islam including Brian Silverstein’s “Disciplines of Presence in Modern Turkey: Discourse, Companionship, and Mass Mediation of Islamic Practice” (2008), Jonathan Shannon’s “Emotion, Performance, and Temporality in Arab Music: Reflections on Tarab” (2008), Prina Werbner’s “Stamping the Earth with the Name of Allah: Zikr and the Sacralizing of Space among British Muslims” (1996).

About the Author

Amira Mittermaier received her PhD from Columbia University. She is an associate professor in the Department for the Study of Religion and the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations at the University of Toronto. Building on over a decade of research in Egypt, her ethnographic work on Islam (and particularly Sufism) has focused on the role of the imagination and the invisible in relation to religious and ethical practice. Her first book, Dreams that Matter: Egyptian Landscapes of the Imagination (University of California Press, 2011), examines Muslim practices of dream interpretation in contemporary Cairo and makes theoretical and methodological contributions to an anthropology of the imagination. The book has won multiple awards, including the Clifford Geertz Prize in the Anthropology of Religion, second place for the Victor Turner Prize for Ethnographic Writing, and the AAR Award of Excellence in the Study of Religion. Her current book project, based on fieldwork in Egypt since 2010, examines modes of almsgiving and food distribution to consider how everyday acts of giving relate to, disrupt, and unsettle political calls for social justice in post-Mubarak Egypt.

Selected Works by Amira Mittermaier

2013. “Trading with God: Islam, Calculation, Excess.” In Companion to the Anthropology of Religion, edited by Michael Lambek and Janice Boddy, 274–94. Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell.

2012. “Dreams from Elsewhere: Muslim Subjectivities beyond the Trope of Self-Cultivation.” Journal of Royal Anthropological Institute 18, no. 2: 247–65.

2012. “Invisible Armies: Reflections on Egyptian Dreams of War.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 52, no. 2: 392–417.

2011. Dreams that Matter: Egyptian Landscapes of the Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Interview

Crystal Brannen: How did you come across the idea for this particular study and topic?

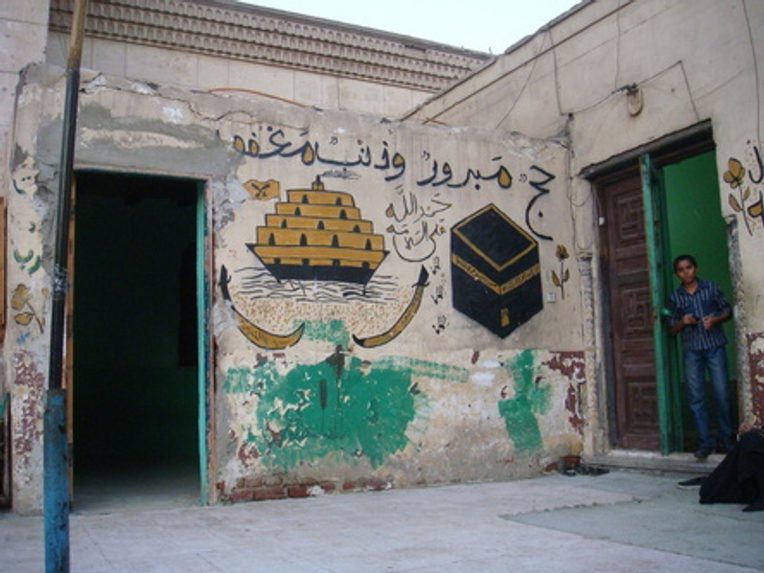

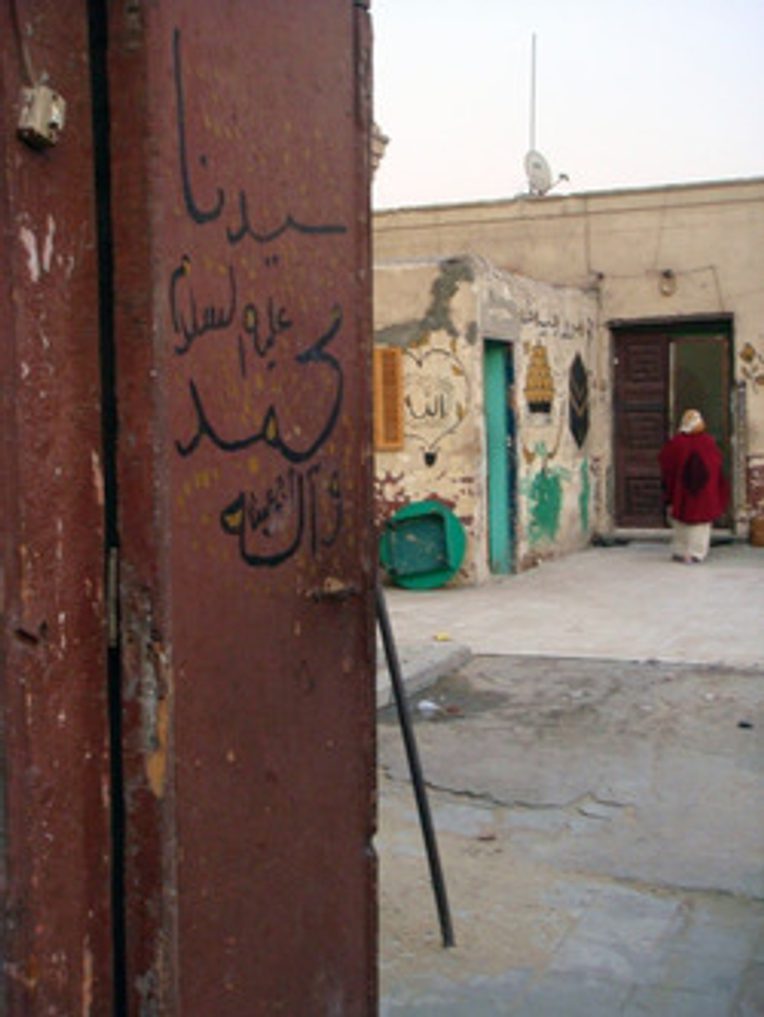

Amira Mittermaier: The article is part of a larger project that looks at different spaces of giving in Egypt. My interest in giving (especially it‘ām, the giving of food) grew out of my earlier work on dreams and exchanges between the visible and the invisible. I had been planning to study giving for a while; then the uprising happened. Concretely, this meant that during my seven months of fieldwork in 2011, I literally kept going back and forth between Tahrir Square (where sit-ins and protests continued to happen) and my fieldsites. The khidma that I describe in the article is one of my favorite places in Cairo.

In 2011, it became a refuge from the clashes and protests downtown—political arguments, violence, and confusion. But over time I also started noticing something different: a certain resonance between everyday life at the khidma and activists’ stories that framed Tahrir as a space of sharing, being with others, and an openness towards others. The article is animated by this resonance and by my literal back-and-forth in the field. It is also a reaction to political party programs that were coming out in 2011 and that to me seemed very narrow and predictable in their versions of “social justice.” One could say the article grew out of a mix of frustration and hopefulness. Today the hopefulness has largely faded; I find the situation in Egypt today very bleak. But maybe that makes it all the more important to think about the revolutionary moment in conversation with spaces and modes of being that precede the uprising and that fall outside of the realm of politics.

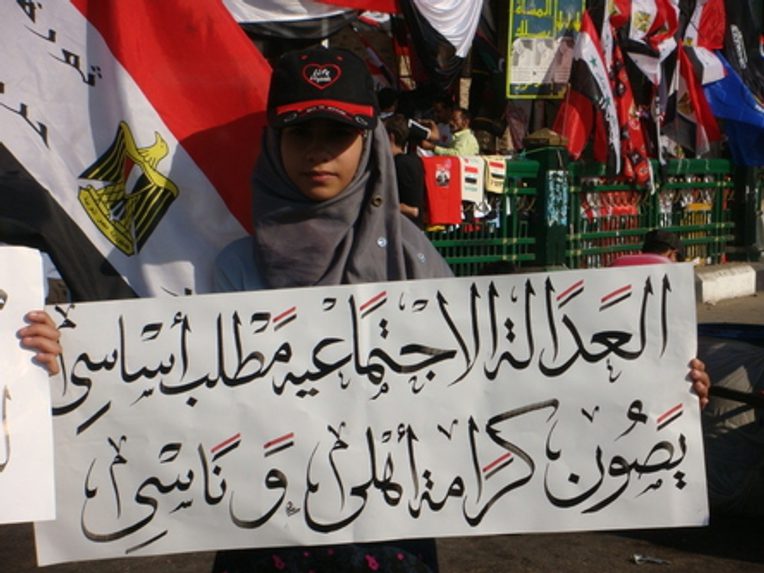

CB: In your article, you mention that Egyptians were deeply concerned about the fate of the revolution and protested for three central demands, “bread, freedom, and social justice.” What do you believe these three central demands represented for these people?

AM: Freedom was key to the protests: freedom from the police state, state oppression, emergency laws, fear. In the article, I focus on the other two demands: bread and social justice. Bread speaks to the material realities of hunger and poverty. I think we can take this quite literally. Think of the 1977 bread riots in Cairo. Or think of the Egyptians that have been killed during the past few years over their spot in lines for state-subsidized bread. Bread speaks to the very question of how to get by in the context of ever-rising food prices, widespread unemployment and poverty, privatization, subsidy cuts, and inflation. My point about social justice is that it’s a very blurry term; that is what made it so powerful and effective during the protests.

There was a certain openness to the term. What I found so striking in 2011 is how the term then became translated into very predictable and familiar (neoliberal) languages in party programs and how it largely came to be reduced to the question of equal opportunities. I’m not arguing against equal opportunities but I find that the focus on everyone’s right to work obscures questions about distribution, the realities of poverty, and something we could call an obligation toward others, or an interdependence. It seems to me that people lived a different form of justice at Tahrir (and at protests, sit-ins, and Occupy movements elsewhere), one that can’t be reduced to the call for equal opportunity. It’s rather tied to a form of together-ness, a being-with and caring-for others in the here and now.

CB: Could you further explain what you meant by the term, “ethics of immediacy”?

AM: The term is inspired by Nura’s ethics (although I’m not sure I want to use the term ethics to describe it): the way in which she attends to those who enter the khidma. Nura doesn’t fight for structural transformations; she doesn’t worry about “the poor” in the abstract. It’s all about those who are here now. I use ethics of immediacy in a spatial and temporal sense: those who are immediately around us, and those who are here at this very moment. I want to think differently about such an orientation, which is often dismissed as shortsighted: giving a man a fish as opposed to teaching him how to fish. Many powerful forces draw us towards the future. One key example is “development” but neoliberalism is quite utopian too. Many Muslim modes of giving are also about the future: securing oneself a place in paradise. Nura rejects the widespread logic of trading with God. For her, it’s about giving now without expecting anything in return. I’m also inspired here by Elizabeth Povinelli’s recent critique of a continuous orientation toward the future—how, in late liberalism, current suffering is justified through the promise, “It will all have been worth it.” But let me be clear here, I’m not trying to say, forget about the future: let’s live in the here and now. I want to open up a space for thinking differently about modes of giving that background the future. I want to think beyond the label “shortsighted.”

CB: How do you believe that khidmas invite an “anthropology of the otherwise” and what is meant by that term?

AM: What drew me to anthropology in the first place is what Michael Taussig describes as its ability to render the familiar strange and to render the strange familiar. I still find anthropology most powerful when it helps undo our certainties and assumptions. I try to use the khidma to render strange neoliberalized concepts of “social justice” and the idea that “work is our only solution.”

At the same time the khidma enacts an alternative, at least on a very small scale: the scale of the khidma. Thinking of this as an otherwise is quite different from thinking about it from within the logic of capitalism. Many would say that the huge number of charity organizations in Egypt, the explosion of volunteerism, and even the growing number of Ramadan tables and khidmas are all effects of the state’s increasing withdrawal of social services; they are a direct outcome of neoliberal transformations.

I don’t deny this but, instead of just reading them as compensatory, I want to think about the possibilities such spaces open up. The otherwise that I find in the khidma points beyond the state and maybe (I hesitate to add this) beyond capitalism. I’m not saying we should all start running khidmas or quit our jobs and start eating at soup kitchens. What I do say is that the khidma, like Tahrir (as a utopian experiment), opens up a space for thinking and imagining beyond prescripted categories.

CB: You wrote in your article that “the khidma and its mode of giving can help elucidate a different mean of justice—one that relates to and stems from human practice, rather than eternal truths. Justice here does not mean that the rich ought to give to the poor, but rather proceeds from acknowledging the profound dependency and interdependency of humans.” Is that in comparison with a westernized view of what justice is?

AM: I don’t want to set up a West–Islam dichotomy. Many of my Muslim interlocutors would say justice means that the rich ought to give to the poor. Some would add that they don’t strive to overcome poverty but simply want to reduce the gap between rich and poor. This is quite different from Nura’s understanding. In turn, “justice” in the West has many different meanings, not all of which work with a poor–rich dichotomy. Some emphasize the vulnerability and profound interdependency of humans (I’m thinking here of Judith Butler’s work, for instance). I’m wrestling in this article—and my larger project—with the idea of justice that we find in Marcel Mauss’s famous essay on the gift. He calls for a society in which the rich should come, once more, to consider themselves as treasurers of the poor. I find Nura’s embodied practice far more radical: she emphasizes that we’re all in need.

I struggled with whether or not to call this a form of justice. Nura probably wouldn’t. But because I want to consider the political potentials of an apolitical space, I purposefully (though uneasily) translate her practices into a language that allows for a more immediate conversation between khidma and the call for social justice.

CB: What do you think is the overall importance of this study?

AM: I’d like to see the article as an example of an unexpected conversation, animated by an anthropologist’s movements in the field. I don’t make a causal argument that links khidma and Tahrir but am inspired by spatial proximity, unexpected resonances, and, at the same time, a complete disconnect. I also hope that the article and my larger project will open up ways for thinking differently about seemingly apolitical, “shortsighted” acts of giving, those we tend to call “charitable.” It’s a common and comfortable position to say that soup kitchens, alms, and other immediate forms of giving cultivate dependency, encourage begging, and stand in the way of true change. I don’t want to romanticize charitable giving but I think of the kinds of distributive practices that I study as part of long-standing religious traditions, ones that involve not only visible actors but also an economy with God.

In the book I’m working on I am particularly interested in the triadic relationship between those giving, those receiving, and God. At the same time, I think about such distributive practices as not merely compensating for the lack of a welfare state but as actually enacting an alternative form of life and care.