Camp as Event

From the Series: Counter Archives: Fieldnotes from the Encampments

From the Series: Counter Archives: Fieldnotes from the Encampments

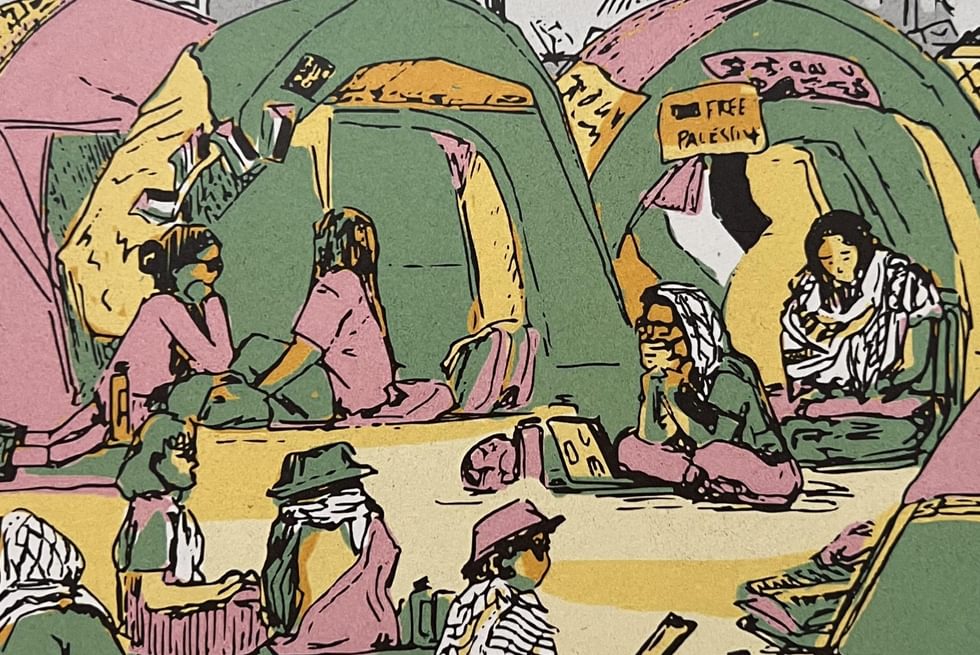

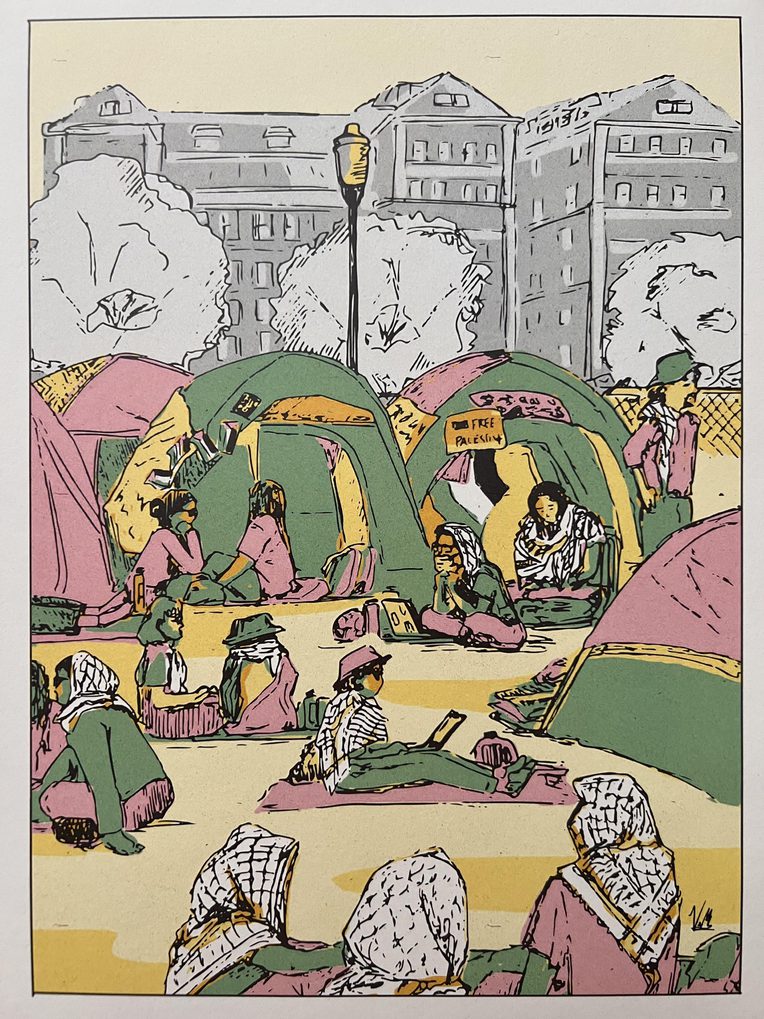

"Camp as Event" was written by Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi, an architectural historian on the faculty of Barnard College, Columbia University, in collaboration with A., F., L., M., R., S., V., and X., current and former undergraduate and graduate students at Barnard College and Columbia University. Drawings are by artists as noted, and photos are by R., except photos by Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi, which are marked with an asterisk (*).

Can we ever free ourselves from the weight of the archive in the present moment? How many years of violence will the improper archiving of this moment perpetuate?

— L.

In April 2024, a question of the camp as form emerged in striking relief to its most immediate iteration in the refugee or detention camp: in which stark formal elements—barbed wire, cerulean blue tarpaulin, and even the concrete structures of Palestinian camps—by being erected through additive processes, emphasize the provisional circumstances of building and inspire visceral reactions, such as fear, disgust, pity, or even a decided fatigue. These architectural compositions perform abstractions of and have come to symbolize abjection, precarity, lack, and dispossession. Scholars have argued against conceptualizing the camp through these narrow interpretations of ephemerality or bricolage in form, instead contextualizing the camp as an event. Yet, what of a protest camp, whose meaning is precisely as event?

I am a professor at Barnard College, Columbia University. I have lived and worked for years in places where sudden, brutal police action is a frequent and often de rigeur strategy to counter and contain political imagination, particularly to suppress academics. This strategy has been unfamiliar in the social formation of the U.S. university for long enough that the events in New York on April 18 and April 30 had a stunning effect. What was it about the encampment that sparked this strikingly overdetermined reaction? Moreover, why did this protest on behalf of Palestinian life and self-determination find its form in the camp?

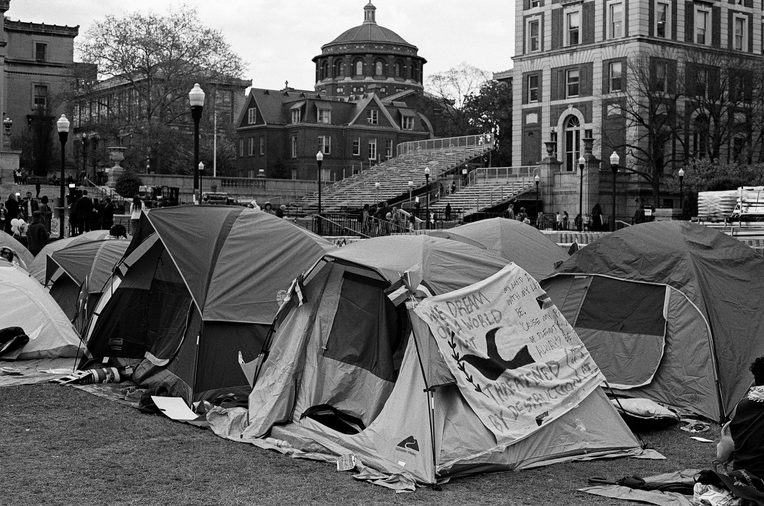

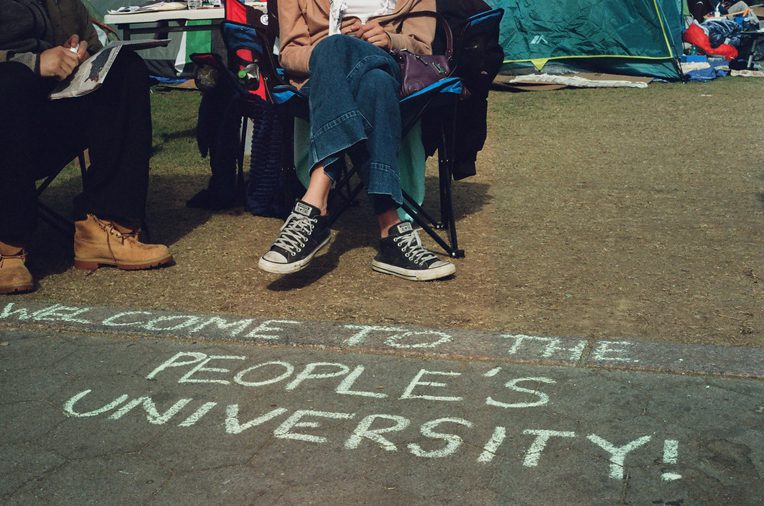

To pose these questions, I write with students who built, recorded, created artworks in and about, or otherwise shaped the Gaza Solidarity Encampment and People’s University for Palestine on the Columbia University campus. We focus on the encampment that flourished on the west side of the South Lawn of Columbia University (sometimes referred to in reports as “the west lawn”) from April 19 to 30. (These dates represent a temporal bracketing of an encampment process that continued beyond this iteration in various forms and locations; first erected on April 17 on the east side of the South Lawn, the encampment was rebuilt on the west lawn after the first arrests—then, in anticipation of the second arrests, both in front of what would become Hind’s Hall and upon an upper lawn south of Earl Hall, and later, once again, on the South Lawn.) In our writing together, we contend with the weight of the archive in the present moment.

That the encampment laid down and also raised stakes hinged on two aspects of its form. The first regards an architecture of ephemerality. A light relationship of architecture to the ground evokes the temporary. Yet, these tents touched ground deeper than—in the students’ words—Columbia University’s occupation of land. If a provisional architecture obscures its will to permanence, enacting permanence seems to have been the subversive end of the protest encampment. The paradoxically ephemeral encampment architecture staked the protestors’ claim to a deeper permanence. This subversion unsettled the authorities—its modus operandi almost more vexing than the content of its message. In this, it echoed its cognate in Palestine, where the camp enacts the right to land through its simultaneous refusal of and claim to permanence.

As college students, our most essential spaces are regulated by the authorities who own them. Columbia University is a campus of artifices—imitations of ancient Greek monuments to the pursuit of knowledge, ominous in their emotional effect. When my mother, who never attended college, first set foot on campus, she turned to me with an anxious smile, looking at the six story columns. “Well, it sure makes you feel dumb.” I believe what the encampment offered was a picture of a potential—a way we might build something, in our hyper-built world, together, organic. Something that symbolized building a better future at large by building something small but physical. Despite the general threat of looming police and disciplinary action, the energy inside the camp was of friendliness and an eagerness to engage intellectually with one another. There are many who joined, attended, sat, even slept, because it was popular, central, and loud, and perhaps wouldn’t have joined out of pre-existing political conviction. What is more important is that it represented for everyone there a taking authority over space that previously existed to regiment, discipline, and quiet, to funnel students off to class and ultimately into the professional world. For undergraduates, graduates, and faculty alike, it felt like a wake-up call not just to the complicity of an institution in global politics, but our own complicity in allowing the built environment to disaggregate our political consciousness as individuals and a community.

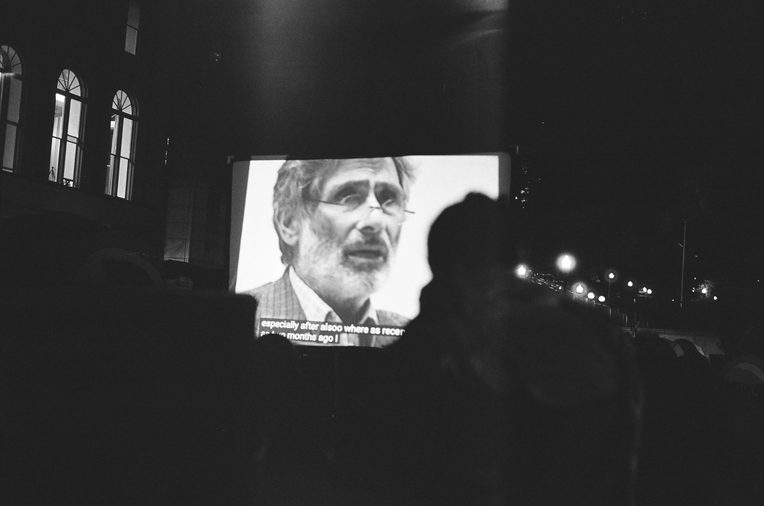

I look at the camp as neither a migratory space nor a re-creation of the conditions of forced refuge or emergency shelter (specifically, in Gaza). Instead, the camp is inextricable from the built urban environment around it, and its purposely performative status. Looking at the camp requires a holistic approach that incorporates the history it sought to replicate and the constant refractions of media attention around it. It was temporary on purpose— fragile, tender, in a way most spaces can’t be— lit by iPhone flashlights, tied to its surroundings: both palimpsest, in the way it sedimented something prior—1968—and mirrored, in the way its juxtapositions were the subject of endless representation on camera, in drawings, atrocities of incomprehensible magnitude played over and over on horrifying screens, engendering the feeling of real moral obligation to try at least something.

— M.

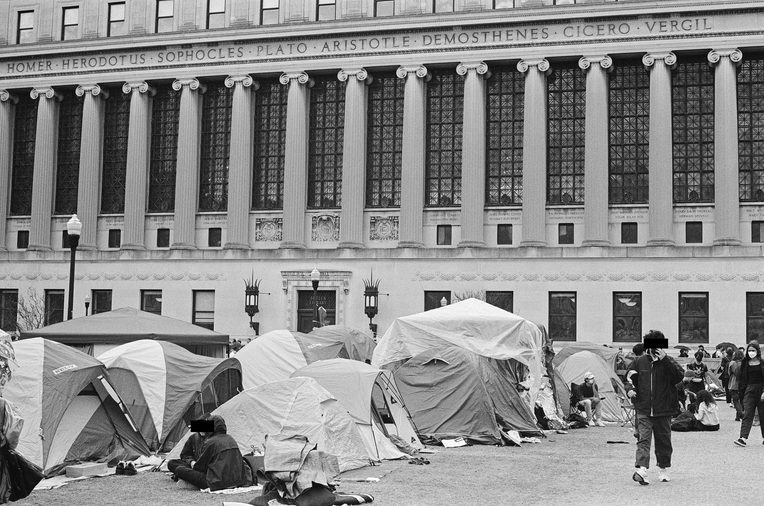

The second aspect of the camp form relied not on subversion, but expression. Protest acts to disrupt, suggesting a will to disorder. Yet, this encampment expressed a highly ordered spatial and temporal arrangement. On the one hand, riotously colorful, soft tent forms on the campus lawn contrasted with the hard edges of the walled boundary hedge and the stylized white architecture by McKim, Mead, and White, articulating a certain representation of Columbia University as well as the racinated academy at large. On the other hand, the encampment’s perimeter tents encircling the open community meeting grounds also constructed a sociospatial scaffold for care, reflecting the students’ disciplined dissent.

The aggressive repression of the encampment reminds us of the ability of architecture to directly signify and confer power, through the visual hierarchy of axiality and imperious neoclassical motifs. Unlike in the defining protests of Columbia’s twentieth century in 1968, 1985, 1987, and 1996, the encampment, delimited by the lawn’s chain-link fence, did not interrupt circulation or disrupt instruction or study prior to police intervention. So what warranted Columbia’s harsh and disproportionate reaction? The encampment arose on Columbia’s most photogenic landscape. By activating it as a space for protest, students also occupied the monumental composition of campus architecture, claiming its visual and physical power.

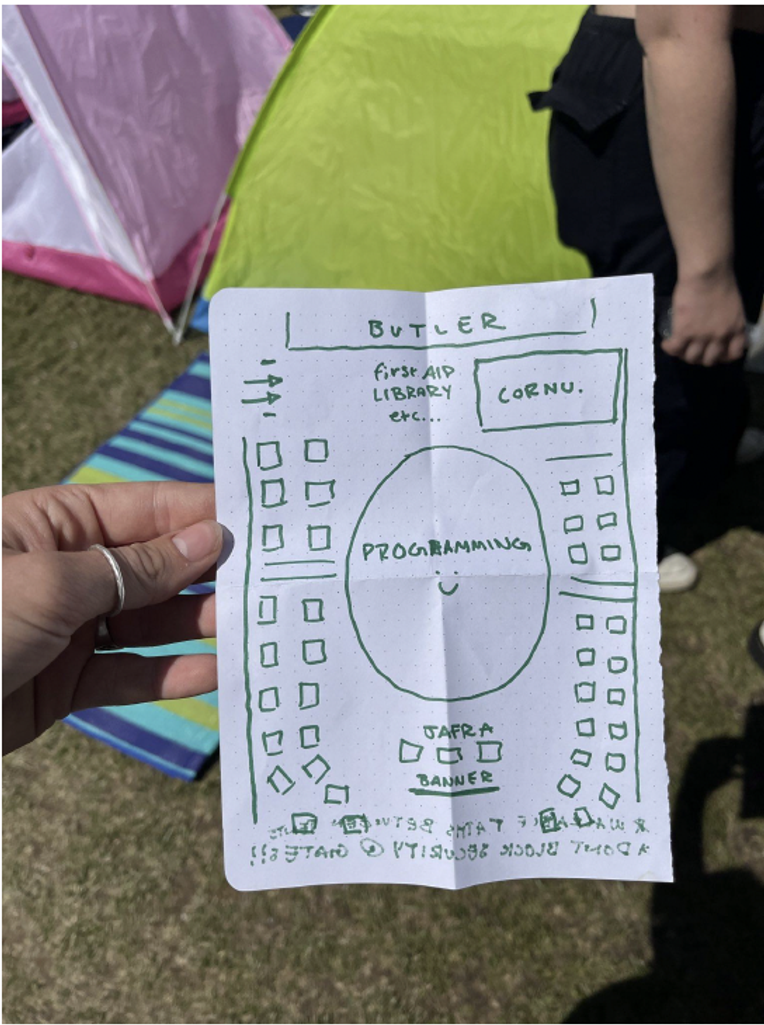

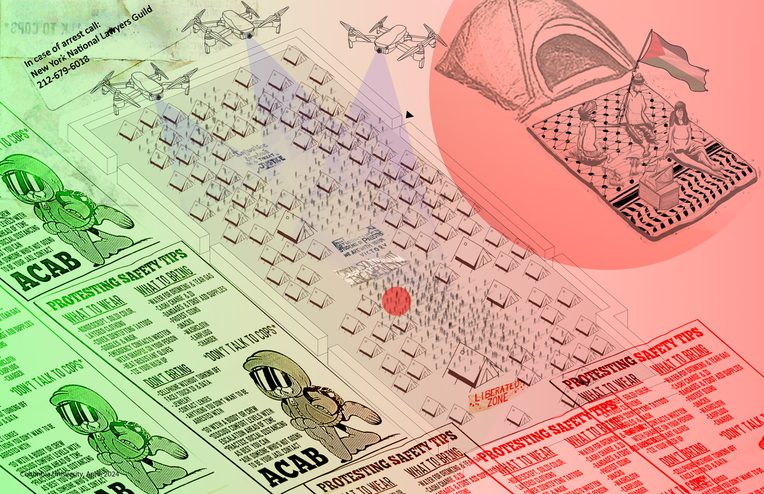

Inside the encampment, tents stood at either side of the lawn, encircling a long, open commons where programming– including dances, chants, and prayer– were open to all, but were organized on a tightly-run schedule. At nightfall, the commons became the site of assembly meetings where encamped students voted on their own administration. The physical planning was logical, but also symmetrical, with a clear progression through the space and service facilities for first aid, food, and water prioritized at the entrance; proportions were balanced; tents were roughly gridded; and a map was drawn to guide growth. The space not only harnessed the order of campus via physical occupation, it reified that order by proposing a reformed alternative university that celebrated the values, backgrounds, beliefs, and passions of its students. This kind of power was clearly too dangerous to go unchecked.

— S.

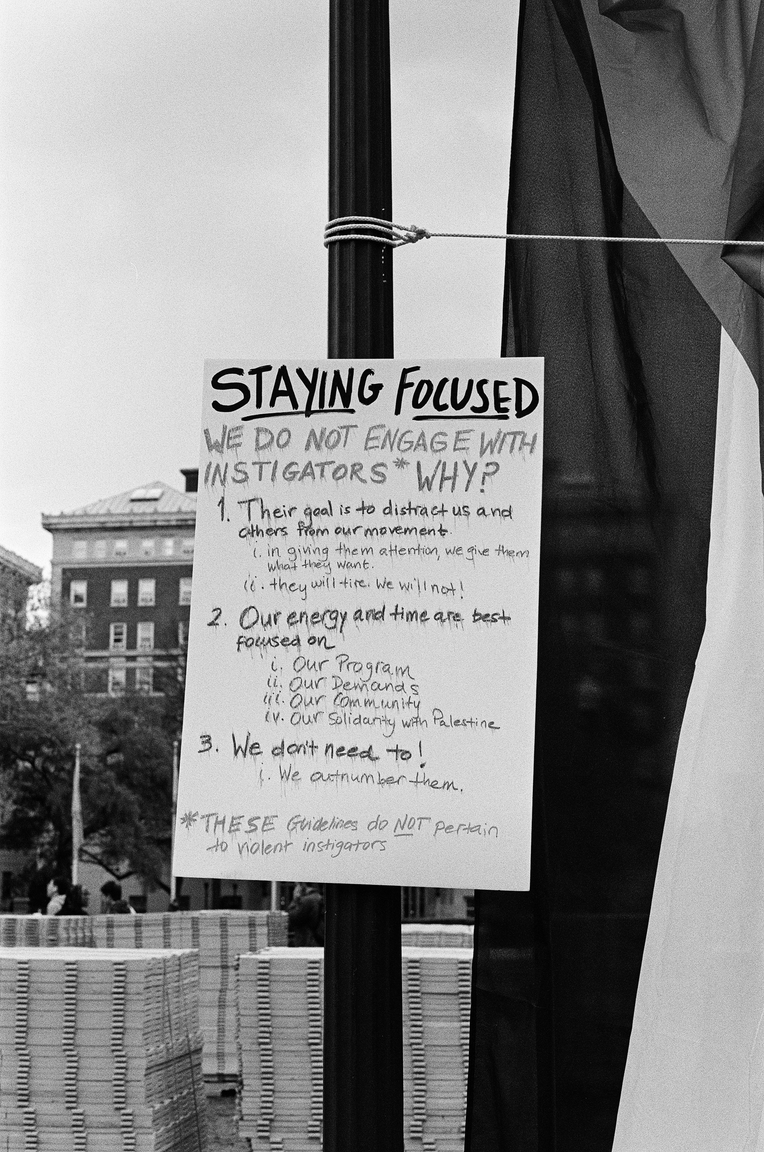

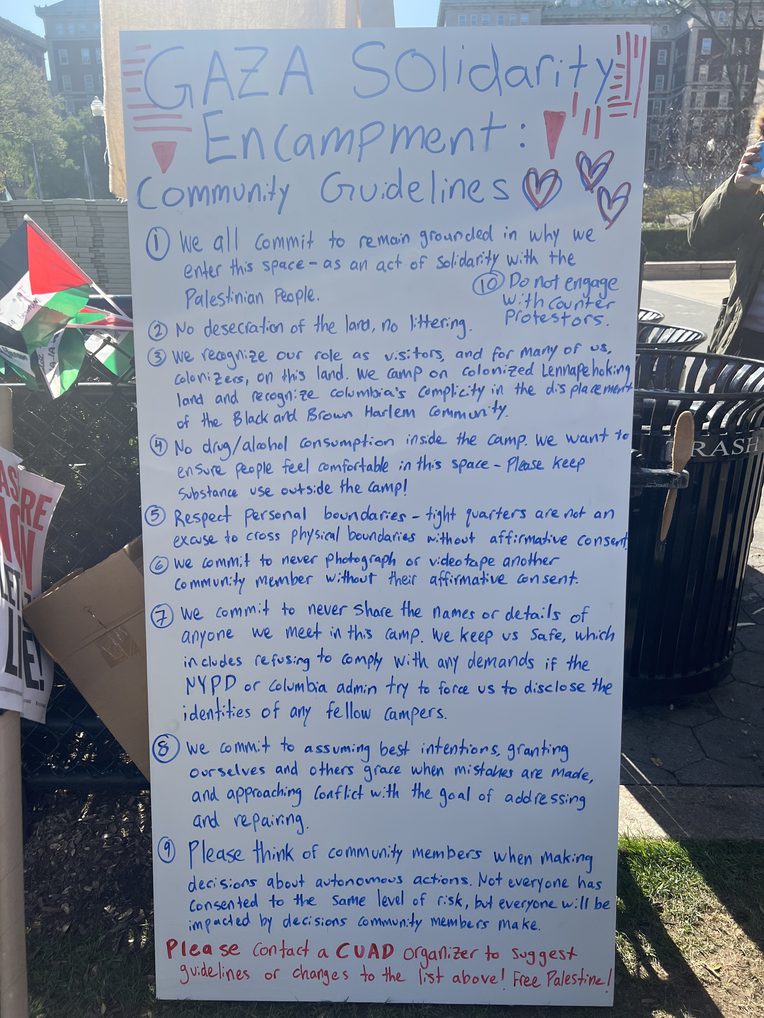

Greeters flanked the entry to the encampment, at the southeast opening in the chain link fence bounded lawn, to direct visitors to a large board listing the Community Guidelines (at one time handwritten, and later printed). Protectors at the entry were joined by faculty and staff members serving in volunteer shifts as crowd de-escalators. Organizers typically limited designated press hours, at first bringing external reporters to a press pit in the southwest corner of the encampment, until later, to accommodate the size of the press gatherings, it was relocated to the plaza across from the encampment entrance, adjacent to the east lawn, at the bottom of the steps in front of Butler Library.

Moving clockwise around the encampment, a first aid station was located in a tent at times on the south and at times on the west side of the entry. The southwest corner of the lawn eventually housed the community cornucopia, the meal and hydration stations, relocated, as the camp grew, from its initial position at the north end of the lawn’s central community space, and run on donations of food and drink by volunteers in shifts.

Tents for community members who either did or did not self-identify in various subcommunities populated the west and east sides of the encampment, encircling the open center. In several instances, Jewish, LGBTQIA+, and other community members represented their solidarities by mounting precise signage on their tents in order to reject and resist the weaponization of their identities. The encampment was designed with various accommodations for differently abled people, and with forms of caregiving and mutual aid in mind, including a Peer Counseling station in a tent on the west side, a Writing Fellow Corner at the northeast, and a table for Faculty Office Hours.

The artmaking station in the northwest corner of the encampment facilitated sign making, painting, silk screening, and arts and crafts production, often integrating visiting children in its activities and serving as a locus for childcare. Students laid out posters in an array on the northern side of the encampment, anticipating frequent photography from above. Surveillance drones hovered above the encampment at any given time. In the art and iconography of the camps, students made historical reference to a lineage of protest at Columbia University upon which they laid claim, creating visual citations of the “Liberated Zone” banners hung across campus buildings in 1968 by mimicking the serifs and style of the painted lettering of those banners in the “Liberated Zone” and “Gaza Solidarity Encampment” signage of 2024.

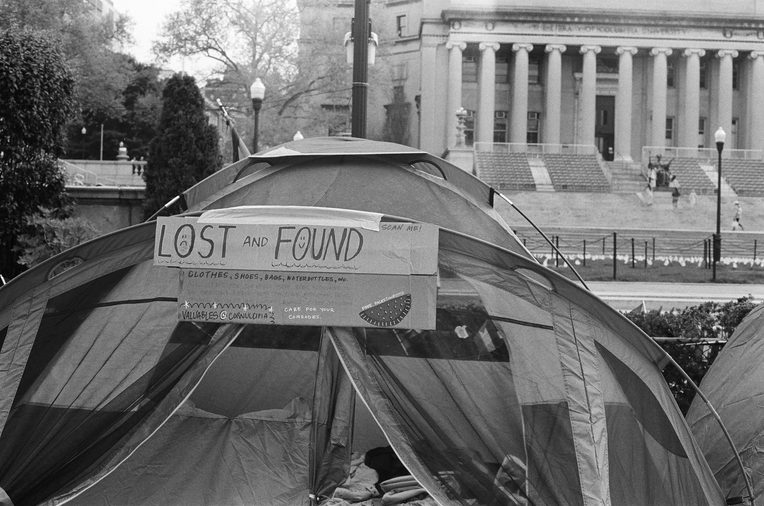

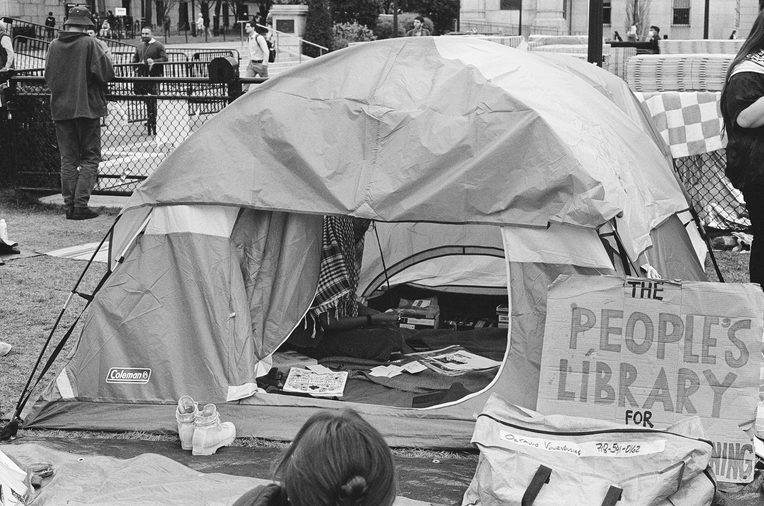

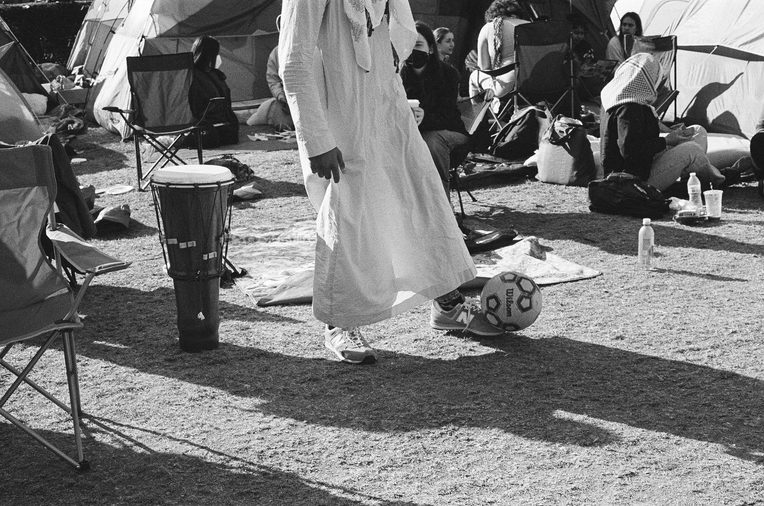

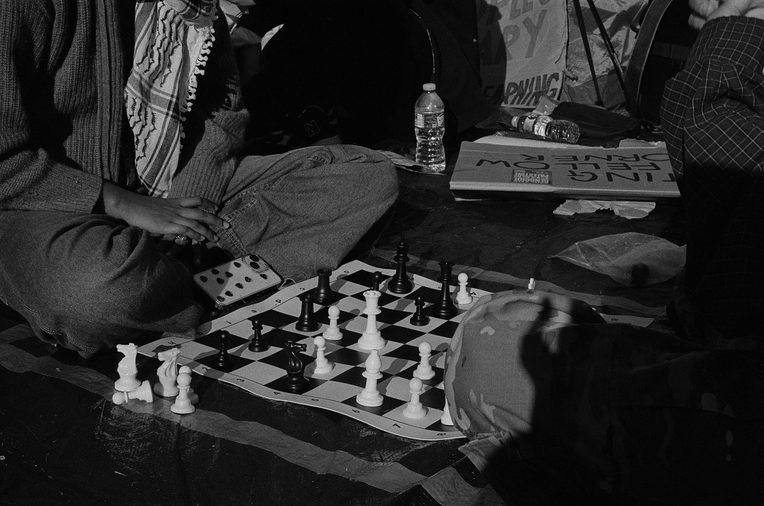

At the north end of the encampment, two service centers became cornerstones of community care: the Lost and Found station sheltering protestors’ valuables and the People’s Library preserving the book collection and the zines made in and about the camp. These and all the tents were arranged to structure the common area in the center of the encampment, which held the program board with each day’s handwritten schedule and the microphones and speakers of the sound system. In the central hub, activities driving the daily life and organization of the encampment took place: teach-ins and talks, dance, music, and other cultural performances, films, games, religious prayer and celebration (with daily Seder during Passover and students holding blankets in a protective circle for the privacy of those within performing Salah/Namaz five times per day), community assemblies, and safety drills.

It is important to keep in mind how real and violent apartheid states are— and in conducting research about anti-apartheid movements, it is vital to avoid conceptualizing “apartheid” to the point where it loses its meaning… After spending two days in the original encampment and facing arrest and suspension from an institution that had promoted “student activism”— and only two weeks later allowed the NYPD to physically brutalize and take over the campus—it became apparent that some of my classmates and professors needed this, in order to apply concepts to real life. One of the most beautiful things to come out of the arresting and healing process was the power of community and love. With the administration turning away from its students, we turned to each other for support and lifting up. These lessons and revelations allowed me to reflect on my research… The thread between the archive, architecture, and incarceration system was eye-opening and revolutionizing for me.

— X.

The regular reporting by student journalists at the Columbia Daily Spectator and WKCR-FM provides a precise narrative and cataloguing of the events that occurred on the Columbia University, Barnard College, and Teachers College campuses, beginning in October 2023. Yet, a careful rehearsal of these events refuses a teleological end in the architecture of an encampment, or the barricade of Hind’s Hall. We may never be able to reason out a university’s decision to harm its own students, but it seems that had administrators met student requests—whether to disclose the institution’s financial holdings and divest from war and genocide, or merely to hold academic and public events to engage debate—an encampment may have been elided. Instead, through its shape, its material, and its touch upon the ground, it produced the ante.

Arguments here owe a debt to Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi, Architecture of Migration: The Dadaab Refugee Camps and Humanitarian Settlement (Duke University Press, 2024) and works it references; students in my 2023–2024 courses, “Life Beyond Emergency,” “Ecologies and Inhabitations of Migration,” “Colonial Practices,” “Partitions, Borders, Camps,” and “Histories of Architecture and Feminism,” who demonstrated profound ways of being together; my committed colleagues at Columbia, Barnard, and Teachers College; a careful reading by Manijeh Moradian; and the reparative historical thinking of Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali Zamindar and Asif A. Siddiqi.