Caught Between War and Dispossession: The Struggles of Palestinian Bedouins in the Naqab/Negev Amid the Gaza Conflict

From the Series: Anthropology in a Time of Genocide: On Nakba and Return, continued

From the Series: Anthropology in a Time of Genocide: On Nakba and Return, continued

These essays in this series were written in August and September, 2024, and may not fully address rapidly escalating violence in the region.

The Palestinian Bedouins in the Naqab/Negev region of southern Israel have been deeply affected by the war on Gaza. Situated nearby, they faced rocket fire threats, often without shelters as unrecognized villages lack protective infrastructure. During the Hamas attack on October 7, several Bedouin community members were taken hostage. Despite these dangers, Bedouin communities remain marginalized by Israeli policies. Many maintain familial ties to Gaza, where Palestinians were displaced from the Naqab/Negev in 1948. As Palestinian citizens of Israel, they experience heightened ethnonationalism, racism, dispossession, and further marginalization.

Amid these threats, Bedouin communities have called for protection, including shelters and inclusion in post-war rehabilitation plans, while facing escalating state-led dispossession. Their demands for civic equality have been critiqued for leading to depoliticization and a detachment from their broader Palestinian identity.

The territorial conflict between Israel and its Palestinian Bedouin citizens is deeply rooted. In 1948, over 110,000 Palestinian Bedouins were displaced from the Naqab/Negev—many to Gaza—losing up to five million dunams of land (Nasasra 2012; Sa’di 2011; Forman and Kedar 2004). The remaining 11,000 were confined to the northeastern Naqab/Negev, and many were later concentrated in state-established townships during the 1970s and 1980s to limit their land claims (Swirski and Hasson 2006).

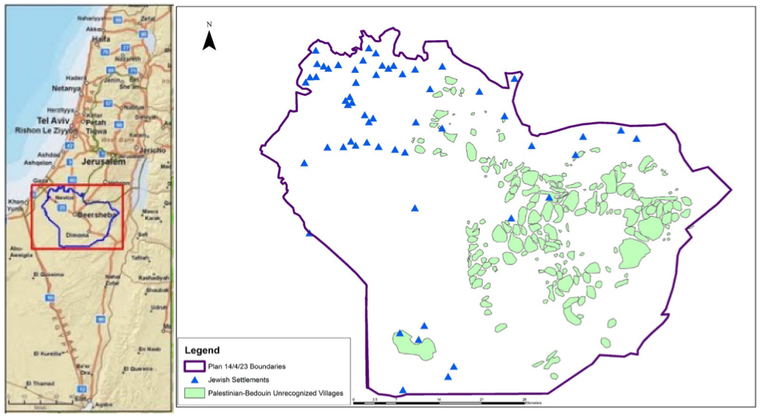

Today, around 80,000 Bedouins (Adalah 2022) live in 37 unrecognized villages (see Figure 1), deprived of basic services and under constant threat of displacement (Yiftachel and Yacobi, 2003; Human Rights Watch 2008). In the past decade, Israeli governments have promoted economic and municipal development in recognized Bedouin townships to absorb the displaced populations from informal villages. This dual process of economic integration and dispossession places Bedouins in a precarious position as they face both neoliberal incorporation and ongoing threats to their land rights.

The Israeli state's approach intertwines land colonization, extreme ethnonationalism, and neoliberal capitalism (Jabareen 2024; Yiftachel 2023), creating a complex interplay of dispossession, privatization, and commodification of culture and Indigenous land rights. This dual strategy—employing both overt violence and reproductive forms of power through development—is evident in the Naqab/Negev, where state-led development projects run parallel to the continued dispossession of the Indigenous Bedouin population.

This dynamic creates a duality in the responses of activists and advocates. Palestinian Bedouin communities must navigate between resisting dispossession through Indigenous claims to historical lands and seeking civic inclusion within the constraints of discriminatory Israeli citizenship. They engage in protests and legal struggles to resist displacement while also participating in state-led development initiatives to secure economic and infrastructural benefits. While human rights organizations and political activists prioritize resistance through protests and legal channels (Jabareen and Switat 2019), local municipal leaders often collaborate with state-led economic initiatives. This divide weakens collective political action as actors oscillate between demands for recognition of their historical lands and the development of previously recognized towns.

For example, the governmental regional strategic plan, Rehabilitation, Renewal, and Development of the Tkumah Region and its Population (2024–2028), excluded Palestinian Bedouin communities and cities, which constitute 27 percent of the region’s population, from its rehabilitation efforts. This exclusion prompted accusations of racial discrimination from the mayor of Rahat, the largest Arab Bedouin city in the area.

Recent government policies have escalated dispossession by establishing new Jewish towns while offering economic incentives to relocate Bedouin homes to recognized towns, giving up their land claims. These towns were initially established to concentrate those displaced from informal villages. At the same time, resources have been directed towards enforcement forces tasked with evictions and house demolitions of “illegal” Bedouin settlements, as outlined in the 2023–2025 governmental plan for “regulating Bedouin settlements.”

Amid the ongoing war, the enforcement of house demolitions in the Naqab/Negev has intensified, with 3,083 “illegal” structures demolished in the past year alone. This escalation is primarily attributed to the influence of Minister of Social Security Itamar Ben Gvir, a far-right party leader. Despite potential opportunities for participatory processes under regional rehabilitation plans, the government has escalated demolitions, undermining chances for regulation and compromise. According to the Governmental Bedouin Development and Settlement Authority, the state’s current approach focuses on destruction without offering alternative housing solutions.

In response to these dynamics, Bedouin political action has fragmented. During the war, their fragile political discourse shifted from broader anti-colonial resistance to a survival-focused civic discourse. Caught in a warzone without state-provided shelters and with familial ties to Gaza, they became increasingly vulnerable, focusing on reconstruction and rehabilitation.

In this context, the National Committee of Arab Local Authorities in Israel sent a letter to the government demanding official inclusion in rehabilitation plans. Amir Basharat, the CEO of the committee, remarked: “During the war, government ministers came to Rahat for photo-ops, but when it comes time to invest money and develop a rehabilitation plan, Rahat—a metropolis for the Bedouin communities—is excluded.”

Municipal Bedouin leaders reframed their cooperation with governmental bodies around local economic development, advocating for civic rights as a form of collective resilience. Integration into neoliberal economic development becomes a tool for expanding citizenship margins and challenging ethno-nationalist exclusion. However, this dynamic weakens Indigenous historical claims and collective identity, raising concerns about balancing the economic commodification of Bedouin lands with ongoing dispossession. By emphasizing economic development as resilience, Bedouins risk undermining their broader struggle for decolonization and restorative justice.

In conclusion, Palestinian Bedouins are caught between state oppression and their precarious conflict zone position, reliant on the state for protection and rehabilitation. Whether the state continues its ethno-nationalist dispossession agenda or returns to strategies of economic inclusion remains uncertain. The future of the Bedouin struggle in the Naqab/Negev depends on navigating the state’s dual policies of dispossession and economic accumulation, and the actions of Bedouin civil society in managing the tension between resistance and inclusion.

Forman, Geremy, and Alexandre Kedar. 2004. “From Arab Land to ‘Israel Lands’: The Legal Dispossession of the Palestinians Displaced by Israel in the Wake of 1948.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 22, no. 6: 809–830.

Government of Israel. 2021 The Economic Plan to Reduce Gaps in Arab Society until 2026. Government Decision No. 550.

Government of Israel. 2022 [altered in 2024]. The Socio-Economic Development Plan for the Bedouin Population in the Negev 2022–2026 and Amendment of Government Decisions. Government Decision No. 1279.

Government of Israel. 2023. Plan for Promoting the Regulation of Bedouin Settlement in the Negev for the Years 2023–2025. Government Decision No. 704/Bedu/2.

Government of Israel. 2024. Plan for Rehabilitation, Renewal, and Development of the ‘Tkumah’ Region and its Population (2024–2028).

Human Rights Watch. 2008. "Off the Map: Land and Housing Rights Violations in Israel’s Unrecognized Bedouin Villages.” March 30.

Jabareen, Yosef. 2024. “The Architecture of Dispossession: On the Dark Side of Architecture and Art in Transforming Original Spaces and Displacing People.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space.

Nasasra, Mansour. 2012. “The Ongoing Judaisation of the Naqab and the Struggle for Recognising the Indigenous Rights of the Arab Bedouin People.” Settler Colonial Studies 2, no. 1: 81–107.

Sa’di, Ahmad H. 2011. “The Role of Social Sorting and Categorization under Exceptionalism in Controlling a National Minority: The Palestinians in Israel.” The New Transparency: Surveillance and Social Sorting, Working Paper V. 1–43.

Swirski, Shlomo, and Yael Hasson. 2006. “Invisible Citizens: Israel Government Policy toward the Negev Bedouin.” Tel Aviv: Adva Center.

Yiftachel Oren, Nili Baruch, Said Abu Sammur, Nava Sheer, and Ronen Ben Arie. 2012. Master Plan for the Unrecognized Bedouin Villages in the Negev.

Yiftachel, Oren, and Haim Yacobi. 2003. “Urban Ethnocracy: Ethnicization and the Production of Space in an Israeli ‘Mixed City.’” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 21, no. 6: 673–693.

Yiftachel, Oren. 2023. “Deepening Apartheid: The Political Geography of Colonizing Israel/Palestine.” Frontiers in Political Science 4.