The following piece is a lightly edited version of a lecture delivered as the Clifford Geertz Memorial Lecture at Princeton University on April 25, 2019, by Michael M. J. Fischer, Professor of Anthropology and Science and Technology Studies and Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Dear Cliff,

In 1976 you wrote, "Art is notoriously hard to talk about. Even when made with words, it seems . . . to exist in a world of its own, beyond the reach of discourse. It is not only hard to talk about; it seems unnecessary to do so. It speaks, as we say, for itself . . . But of course, hardly anyone . . . is silent . . ." (Geertz 1976, 1473). So begins "Art as a Cultural System," in the course of which you consider Abelam art (cosmic and ritual), Renaissance art (religious and calculative), and Arabic poetry (sparring and dialogic). The essay ends alluding to Wittgenstein's notion that meaning arises in use—that what we need in discussing art is less cryptography and rather what you called a new diagnostics, "a science which can determine the meaning of things for the life that surrounds them . . . to locate in the tenor of their setting the sources of their spell" (Geertz 1976, 1499).

I want to pursue this thought and ask how meaning arises in artistic practices that attempt to grasp our emergent technological lives. These practices are often articulated in terms of scientific arts, or of a curiosity about the world and a joy in discovery that the world doesn't work the way we thought it did. They are attuned to changing notions of common sense in different parts of the world. I want, moreover, to examine this question in places like Singapore, Indonesia, or Thailand, where the categories of both anthropology and art criticism seem antiquated to what is going on, and where certain art practices seem to speak back against the simplicities of globalization, postcolonialism, neoliberalism, authoritarianism, and corruption, and do so with a sophisticated cosmopolitanism both locally rooted and globally informed.

"The contemporary," the curator-category for art that comes after the "postmodern," is not very helpful here. It evacuates or at least dulls both the specificities—geographical, historical, and technological—and the internal contestations of critique, different framings, and alternative perspectives. Art markets and patronage structures exert political economic pressures that many art practices in Singapore and South East Asia contest in a kind of para-site fashion, deploying what we used to call immanent critique or critique from within. Although much of commentary on art in Singapore and Southeast Asia is still coded in twentieth-century terms of identity politics, obsessions with history, and liberal gestures towards multicultural dialogue, I wager that something new is being made evident in Asia. Here, there is a new form of synthetic realism—expressed in both an openness to the technological future, and a critique of the transnational present that is hard to find in Europe and the United States. This synthetic realism is made up partly of gritty survivorship of war (both World War II and the Cold War with its guerrilla insurgencies and rough security state responses), and partly of an ability to metabolize transnational circulations into local and regional gaming. Gaming, artificial intelligence, bodily practices, and molecular and ecological sensibilities all contribute to a new Asian common sense for the twenty-first century. Singapore is an experimental space for the meritocratic world's thin membranes of control and out-of-control life. Art lies in the fault lines of culture, sometimes as sparkling gold, sometimes as water, ice, and gas that expand and crack the fault lines further open. Singapore is of interest because it is so twenty-first century, so first world, and yet geographically afloat in the deep exchange circuits of Asia. It is, on the surface at least, hypermodern, testing all the newest technologies from self-driving vehicles to blockchain fintech.

I'm interested in what I will call light shows, shadow plays, and pressure points and will try my hand at a tactic you, Cliff, once called slideshows of lives and works (Geertz 1988). Three more rules of writing I've imposed on this experiment. First, can one compose an ethnography of a place, or global skein of networks—I am still my father's son, half geographer—using primarily a montage of artworks and the discourses of the artists, privileging the artists rather than constantly referring to Euro-American theorists? Second, can one do this with a balance of female and male voices, and a balance of ethnic voices beyond the official plural society's four "races"? Third, can one write a piece on Singapore without personalizing it in the figure of Lee Kuan Yew, the longest serving Prime Minister? What is the balance of immersion versus explanation that listeners/readers can absorb?

The fault lines I focus on here involve safe seas, gender relations, muscle, and emotional memory in performance arts, civil society activation, and smart society biopolitics. The technological media range from high-end video and subliminal music, to calligraphy in rattan and yoga, to collective language learning and artists' networking.

Picture Languages and Meaning in the Ages of Kino Eye and Video

I begin with Charles Lim's ten-year-long construction of an artistic vocabulary with which to see usually invisible infrastructures of Singapore. Lim’s art allows us to see these infrastructures as a growing, greening sea state, linked undersea with fiber optic cables, by sand-mining across Southeast Asia, and dug down into the rock under the surface. Insofar as we are likely to become increasingly more, not less, dependent on living in, on, and under the sea, Lim's project is an ecological biophysical future-oriented one, and thus also a critical anthropological one. His project, he says, is “a way . . . to force the issue . . . Using Singapore as a laboratory . . . destroying Singapore as a national narrative, I'm actually breaking up [the national narrative]. You know Singapore doesn't really exist at all” (personal communications, June 2016).1

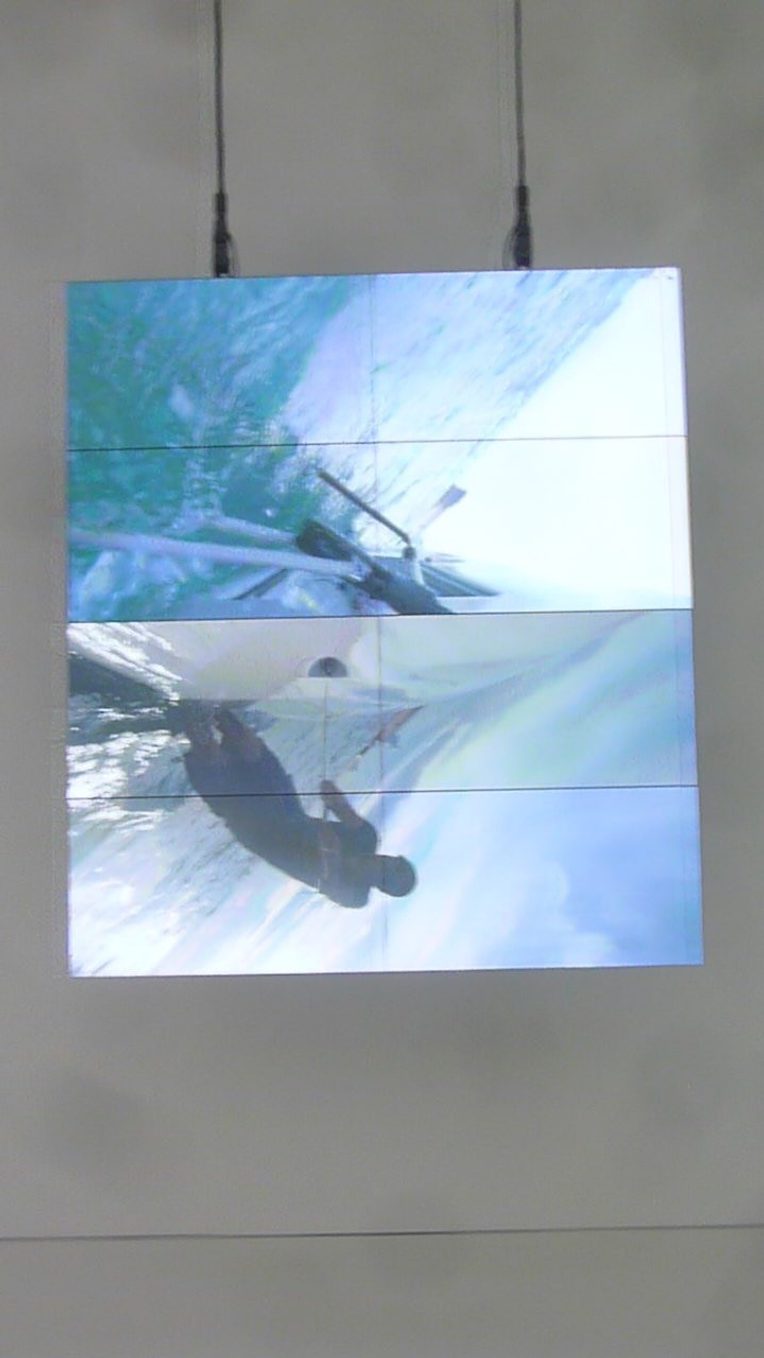

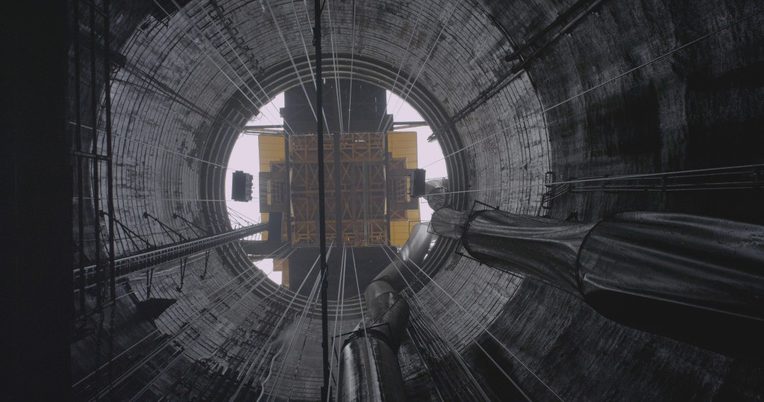

“I devised a strategy for my work where instead of trying to come out with a position, like a political position, what I did was execute a gesture . . . through which these situations expand. . . . It's like an experiment” (personal communications, June 2016). Lim’s work is neither documentary (repeating what we have already seen), nor does it indulge in tropes of the alien sea (cold and sublime). The sea is warm, socialized, permit-ed, and regulated, flowing around proclamations, buoys, and contributing its own culture or forms of knowledge, its own flourishing and modes of action. Lim compares his strategy to an inverted pyramid, building out from a minimalist gestural point—not unlike the ethnographer's frequent starting point from a vignette. In an important way, his work also aligns with recent historiographic efforts to reclaim sea-based histories from land-based and continental ones framed by empire. His camera eye is often geometric, cutting the visual field with a razor’s edge, immersed in the water or gliding evenly over it, silently surveying, observant, with only the sound of water as he capsizes or minimalist music compositions. These dynamics are evident in two of his pieces, “Capsize” and “Caverns,” where two plasma screens face one another (see below). In one he capsizes his sailboat, and the image follows his circular movement into the water and back up onto the righted boat, with the water sometimes above where the sky should be and sky beneath. In the facing screen, we go deep underground with similar geometry, down the huge circular elevator shaft into the whale-like oil storage galleries. As the sound from one screen dies down, the sound from the other rises up, directing our gaze back and forth. Men carry the sailboat through the cavern in a noir premonition of living under the sea.

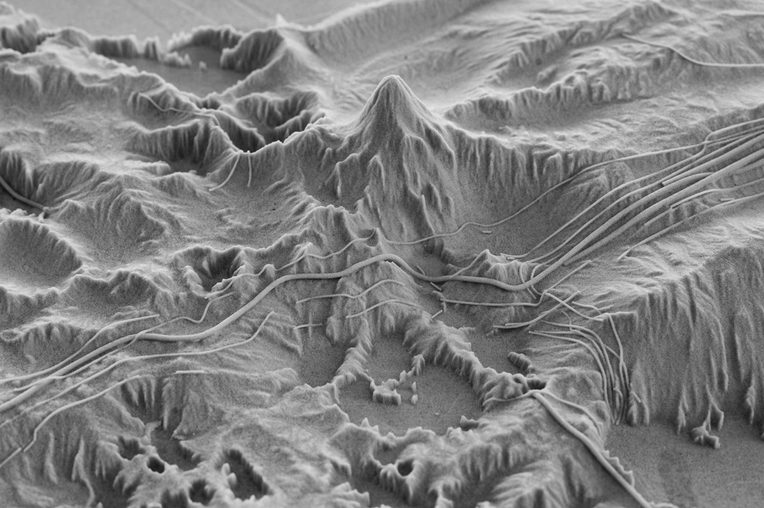

Lim’s ten-year project “Sea States,” which represented Singapore at the 2015 Venice Biennale, references mariners' nine levels of turbulence from untroubled waters to typhoons. “Sea State Zero” or "all lines run out" exposes the infrastructure, or the fractures in the culture, of the longkangs. These are part of Singapore's storm drainage system—placid greening canals, although as Lim says in an interview I conducted with him, Singaporeans are proud of their drainage system because unlike Jakarta and Bangkok, Singapore doesn't flood (or only a little so far). One backstory of "all lines run out" is the escape from the old high-security prison at Whitney Detention Barracks of the suspected Jamiyaat Islamiyaah terrorist, Mas Salameh, through these drains, flushing him out to sea. Lim lightly alludes to this in a scene of a man being washed out to sea, but the film focuses on other themes: cleaning the drains and observing micro-life forms in the water. There is a strong tendency to over-read the political subtext in Lim’s work: it’s there, but politics in Singapore, as in Java and Thailand, does not work well when it is blunt, and Lim's insistence on gestural strategy is an alternative politics of curiosity. In a later segment of “Sea State,” Lim maps the sea floor with sonar and turns it into an inverted 3D relief map of sand, bringing the undersea internet cables into view.

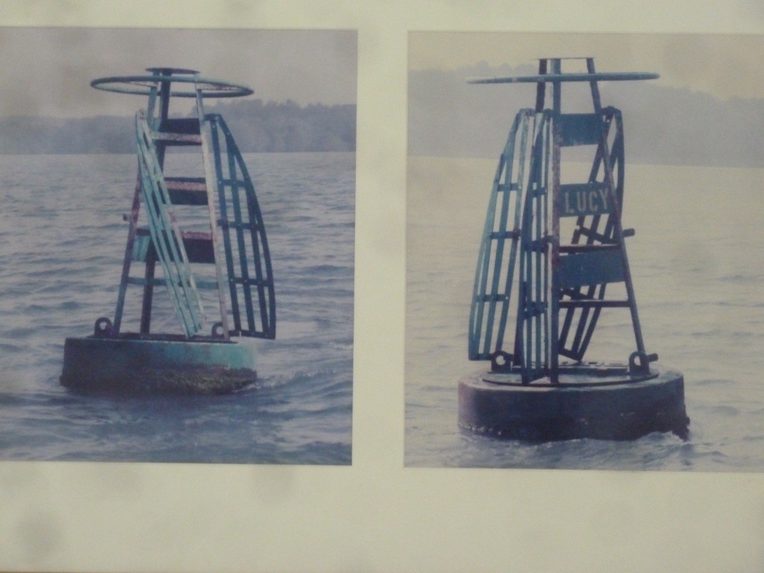

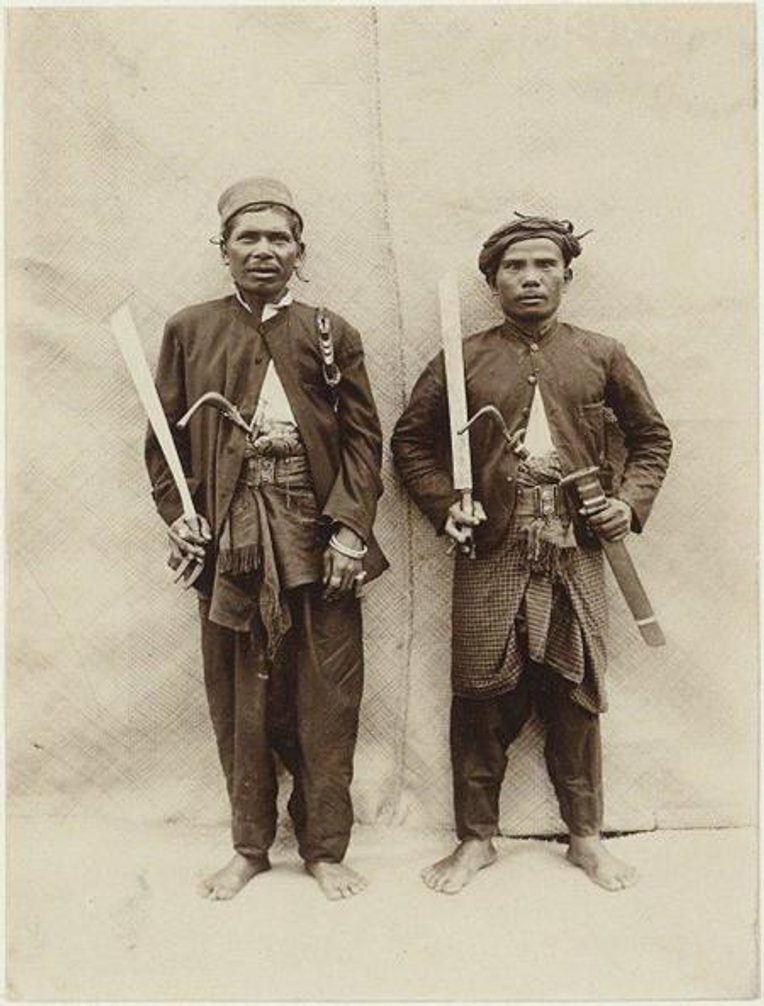

In “Sea State 1,” or “Inside/Outside,” pictures of a hundred buoys are lined up on the wall in pairs of front and back views, looking out to sea and back to land, their shapes reminding me of seventeenth-century Achenese marines lined up for battle with Portuguese intruders (see below). Buoys and lighthouses are beacons and warnings of rocks and shallows. They are meta-stable figures of off-shore temporary autonomous zones: special economic zones (SEZs), penal colonies, quarantine stations, military training zones, spaces of camouflage and commodities laundering, and industrial off-limits zones. They project interior discontents and anxieties onto outside spaces: fortified islands, territorial water markers, beacons of safety, and zones of exception.

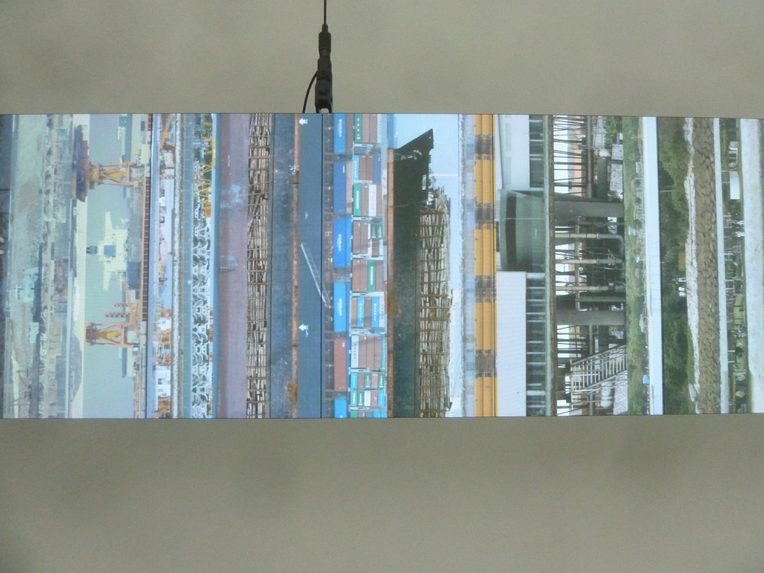

Sajahat or Evil Buoy, off Sajahat (Evil) Island, both of which disappeared off navigational charts between 2000 and 2012, gives its name to “Sea State 2,” “As Evil Disappears and Safe Seas Appear.” The evil that disappears is not in the past, but what occurs in the present while we are distracted. Sand and land, even islands, disappear and reappear as land reclamation. The enabling extra-legal maneuvers occur out of sight, under national security imperatives, and subtly through contracting, permitting, and other camouflage. The key display in “Sea State 2” is a long "sandwich" of videoed strips of the coast turned 90 degrees, placed side-to-side so that the strata of tropical blue sky, water, and white sandy horizons appear as abstract vertical strata. The strips move up and down, as so many moving parts of the shore: port activities, container wharfs, and boats dredging sand from the sea. Lim cut the video in half. Half was water, half was land; he cut the water half out. But, as he says, the land that you see used to be sea (it is reclamation land, sand from the sea). It remains under the Maritime and Port Authority, marked on navigation maps as still part of the sea until it gets consolidated and is transferred to the Land Authority by proclamation. The legal proclamations changing the status of sea and land are the magic of the state. In 1973 life and the sea became radically desocialized when Singapore reactivated the old British Foreshore Act, making it possible for the government to seize the shorelines and begin the major land reclamations. Disappearing islands are, for Lim, part of a broader effort to put out of mind what happens at sea. Together with Takuji Kogo of The Candy Factory, Lim spoofs a 2011 naval recruitment ad, adding electronic music and a robotic voice singing the words of the ad, as the images spiral down like the nose of a missile:

We all take the sea for granted, but that would not be possible without the advanced naval technology that is deployed around our shores. Take the sophisticated Harpoon Missile. Smart weapons installed on the navy's missile Corvettes can destroy targets as far as 90 kilometers away. To avoid detection they travel at blistering speed just a few feet above the waves. They are deadly and they are dependable, but what is the best thing about these missiles? They make sure you don't even have to think about the sea.

Ever.

Life wouldn’t be the same without safe seas.

I begin with Charles Lim for his inventive use of video, his attention to the transformation of the infrastructure (Internet, canals, drilling underground caverns, and plans for building under the sea) opening to view the fault lines of the political economy of land reclamation and the national security state. Think of what a similar project about the United States would look like.

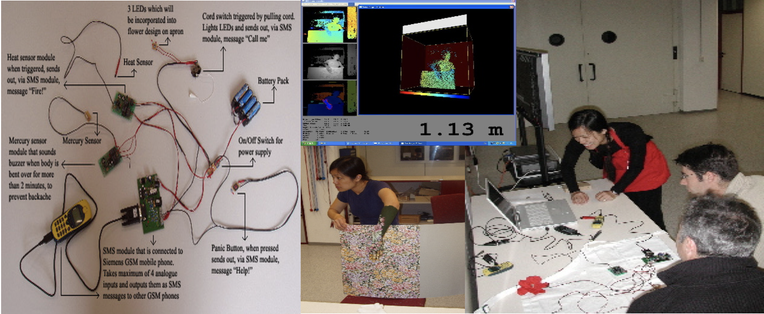

Deep Play, Shadow Play, and Gender in the Age of Filmic Reruns

Equally challenging to make visible, as the Internet and safe seas, are social infrastructures such as local women artists' networks. These are activators of civil society and feminist gender relations within the Intelligent State and Smart Nation, two of Singapore's brandings. Bringing gender relations out of the shadows is often feminist work, not only for gender roles but for many other issues of identity, power, and social justice. I think here of Margaret Ai Hua Tan's “Smart Apron” as a probe for thinking about wearable computing and mobile technologies, fitted with sensors that send SMS messages about falls or about staying bent over too long, in order to make visible domestic work and especially that of foreign domestic labor (see below). I also think of Shirley Soh's work with female prisoners producing craft works about their lives and futures for display in art expositions to show these women as relatives rather than abject others. And, recently, I also think of Sandi Tan's work in both the 2018 film Shirkers and her follow-on novel, The Black Isle, charting feminist fault lines and emotional structures in the obsessive retellings of Singapore's history (Tan 2012).

As technological media, film plays with time, afterimages, and rapid shifts of directed attention, while the novel arose as a vehicle for the double consciousness of being in two worlds at once, with the corresponding imperative of individuals to seek out information rather than rely on communal common sense or traditional moral tales of how to live. Sandi Tan's film and novel probe the poetics of power, genre forms of storytelling, and the way hauntologies destabilize presumed ontological fixations (or false claims about the fixed nature of reality, whether gender roles, official political histories, or neoliberal imperatives) (Derrida 1994).

The film Shirkers—which won the 2018 Sundance award for best world cinema directing—is about the failure to complete a film that Tan and two other girls, then in their late teens, attempted to make, under the influence of a film instructor, Georges Cardona, at The Substation, Singapore's independent artists’ venue founded in 1990 by Singapore's great bilingual playwright Kuo Pao Kun. Shirkers was an improvised do-it-yourself film, in part about saving images of a Singapore fast disappearing through urban renewal. It uses a campy story line, including shooting various characters with one's fingers (spoofing François Truffaut's 1960 Shoot the Piano Player among other film references). Cardona was supposed to edit it, but never did, and the film disappeared as did he, until twenty-five years later when seventy canisters of the 16 mm film shots (in ten-minute segments) showed up. After years of embarrassed, disabling silence—not being able to talk about a film that had never been made, for which there was no proof that it had ever existed—Tan is enabled to make a new film with bits of the old. In doing so, she re-experiences something of the girl empowerment that she had felt during the making of the original film. The new film becomes a psychodrama about the ephemerality of Georges Cardona, the guru or daemon, who cast a spell not only over the three girls but also others he enticed into projects that never came to fruition. As Tan repeats over and over, she cannot bring herself to vilify Cardona. He is still the best storyteller she's ever met, and he turned her teenage film infatuation into a taste of empowerment through filmmaking and story-telling.

Before the film canisters reappeared, to exorcise not just the loss of the earlier film but the devastating loss of a feeling of free agency, Tan began writing the novel, The Black Isle, an art form not dependent on unreliable collaborators. She says,“My aim was to write a novel about an Asian woman who’s neither driven by grievance nor defined by marital or filial relationships. I felt that those were the types of Asian heroines found too often in novels. . . . I wanted to give my heroine the freedom to be her own person, to be complicated in a modern kind of way—and then see where a woman like that might take a story." The novel, like the film, reconstructs a life, she says, "of a young woman with extraordinary powers who falls under the influence of a charismatic but sinister man.” However, I read it as under the influence of three male figures, three different daemons or forms of deep play, with the protagonist becoming herself in the process such a daemon too, one that traditionally might have been called, and is so intimated in the novel, as an angry female ghost or sorceress.

While narratively more complicated, the novel also has a first-person voice concerned that the past not be disappeared. The past, like the imagined future, is always with us in various forms that I'm calling shadow plays (but that local film and literature often evoke as sorcery, spirits, and ghosts). Shadow plays flicker and fade, repeat and sometimes resolve into immemorial images that can re-traumatize, become further encrypted, or just become part of resilient maturity, like the bamboo or rattan that bends in the wind but does not break. The point of films and novels like Sandi Tan's are in part healing gestures for the wounds of our histories. In pursuing histories, we are always running after the fact; and the problems have only intensified in today’s digital and controlled worlds. The libraries might decay, documents may be redacted, books trashed, and histories rewritten. So, as with the problem of transmitting nuclear contamination messages a thousand years into the future, we need to create flexible forms of cultural transmission that, like translational medicine or acupuncture, can administer the emotions, conflicts, and cultural resources of the past, so that repressions not disable, repeat, or explode our capacities to understand our worlds.

Both Tan’s film and especially her novel suggest that film songs and genres—not necessarily of the diegetic time period, but as analytic probes—might be useful cross-temporal tools for the interpretation of cultures that are themselves not of one time horizon or one locus of the imagination (Geertz 1973). “Very often, images come to me before words do,” Tan says. "I wrote the book with several movie sound tracks on a loop, including . . . There Will Be Blood and . . . The Talented Mr. Ripley— and composed the whole thing as kind of a movie of my wildest dreams . . . As if some fantasy amalgam of David Lynch, Alfonso Cuarón, and 1970s-era Francis Ford Coppola were directing The Black Isle in technicolor.”

The Black Isle continues the study of daemon or guru figures—I count Georges Cardona as the art daemon—whose passions are never exhausted, and around whom the female protagonist must negotiate while protecting her sense of self. These include a Malay bomoh (master of the spirits) called by his Chinese employer by a generic Muslim name oblivious to the cultural, not just the class, erasure; a Japanese commander who takes the protagonist as his trophy wife and cultural opponent through the hells of wartime brutality; and the key politician of a cleansed meritocratic post-war Singapore. I call them the daemons of autochthony, of warfare, and of rationality. Or one might call them tropical fevers: the archive fever and hauntology of spirituality located in old Malay thalassocracies; the war fever of tributary extraction, co-prosperity spheres, and national security states; and the meritocracy fever of out-of-control rationality.

While these guru-demons and fevers are male and patriarchal, the novel is constructed by its female author to imagine a woman protagonist—"unlike the heroines of most Asian novels.” That, too, was the intention of the original film Shirkers: to do and create without barriers. It was both a mood of the times and of her stage in life. But with age comes experience and the novel's heroine significantly changes her name from Ling to Cassandra. She also becomes a daemon in her own right, marginalized by history—not a traditional pontianak (angry female ghost, usually avenging women who die in childbirth), but rather a once charismatic figure of female agency, who works to outwit the historians and keepers of the archives from erasing her.

The World War II section of the novel is written à la There Will be Blood (a 2007 film by Paul Thomas Anderson about the landmen in the American West who forced and swindled people into giving oil companies rights to drill under their land). The Black Isle is governed not only by the extractive desires of that film, but also by the noir, nightmare, and survivor genres of World War II in Asia, which foreground cosmopolitan gentility, veiling deadly games of sexual and political treachery, such as in Eileen Chang's (2007) novels of Shanghai adapted to film by Ang Lee in Lust, Caution (2007). Horror and Japanese sexploitation films are also evoked. After such intensity, the novel's prose drops in emotional tension, aligned with the postwar return of the British, and the now emptiness of their imperial assertion, bluster, and spectacle.

The final section of the novel is written à la The Talented Mr. Ripley, a 1999 film by Anthony Minghella about a chameleon-like suave and expert player, who steals the identity of a Princeton student requiring cascading maneuvers. This section of the novel is about the political struggle to transform Singapore under the daemon-guru-charismatic figure of Kenneth Kee, a near homonym of Lee Kuan Yew. Thinking of Kee through a film genre puts a memorable spin on his passion and legacy, and frees this portion of the novel to be about the poetics of power. At one point, the teller of our tale, Cassandra, describes him as a man obsessed with Han Fei, the philosopher of statecraft who advocated for a leader who is “so still that he seems to dwell nowhere” (like Geertz's description of the center of Negara the Bali theater state) (Geertz 1980), and thinks he would be kinder if he instead read Machiavelli.

The novel is one of many obsessive retellings of the history of Singapore in competition with state narratives. There is some effort by Malays and others to inscribe an older history than that told by the state, which insists on an Anglo-Chinese centrality, not even so much out of chauvinism (though there is that too), but out of a commitment to a certain kind of hyper-modern work ethic.

Writing about subjectivity in the twenty-first century cannot be divorced from contested political histories. Or said another, more literary way, behind or alongside every ontology or everyday ordinariness lies a hauntology. Hantu in Malay means ghost or specter; haunter in Old French (from German) means home, one's haunt. A spirit or ghost haunts a house, or recurs persistently in consciousness. At times when the return or repetition detects a difference, the heimlich, feeling at home, becomes unheimlich or uncanny. It is these emotional differences that inhabit and create the sensing of ghosts, specters, or spirits, and that also help constitute subjectivity, the orienting immune system of the self formed through relations with others. When the ghosts disappear, the self becomes disoriented, shadowless, insubstantial, without its parts, and pale, lacking the reflections of him or herself in others, and thus unable to engage in the healthy interactions of living, drained of blood, and thus of life.

This is the message of two of the sorcerers. One is the bomoh-Malay guru, the keeper of Malay repressed histories, life styles and aspirations. The other is Cassandra, the keeper of alternative female perspectives, such as those being made visible by Margaret Tan, Shirley Soh, and other feminist artists in efforts to build collaborative civic action and human-scaled public art within the spaces of the Intelligent Island and Smart Nation.

Primordial Sentiments and Civil Politics in the Digital Age

Singapore is still a plural society, created upon layers of pre-colonial thalassocracies. Minorities in Singapore are generally grateful for the protections afforded by the secular public order—things were and are worse elsewhere—and, with a sense of humor, one accepts the limited choices of official identity as Chinese, Indian, Malay, or Other (CIMO). Theater and the arts provide opportunities to weave more identities and histories into the cultural fabric. It is there, as well, that one can explore high-tech biopolitical futures, current meritocratic pressures and identities that do not fit the four-fold CIMO classification, binary gender, or the pressure to identify Malay with Muslim.

The 2017 novel Altered Straits by Kevin Martens Wong (2017), for instance, reimagines Singapore's Merlion mascot as a species of genetically engineered symbionts paired with elite human soldiers. These form Anthronaut incubators for human enhancements, such as regeneration of injured limbs, or the ability to hold one's breath underwater for long periods of time by using the myoglobin that sea mammals have. The battles they fight are fusions between the historical battles among thalassocracies of the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries and those of the future, in which alliance structures may look quite different than the geopolitics of today. The author is himself one of the category of Other, a Eurasian with a degree in linguistics and anthropology, and is engaged in a CoLang project to retrieve Kristang, the language of his Eurasian-Portuguese ancestors. CoLang, as many of you may know, operates under the Linguistic Society of America, and is dedicated to teaching indigenous peoples, or speakers of creoles, whose languages are at risk of dying, how to collaboratively keep them alive. Wong teaches Kristang, although he did not grow up speaking it—the last in his family to speak it fluently were his great grandparents. Most of the people in his classes have no necessary connection to the language other than that Kristang is part of Singapore's heritage. They have fun creating new words to keep the language alive—some inventions take and others don't, just as in other natural languages. One might see at least a metaphorical resonance between the novel and his identity: he is, in a sense, a Merlion, come by sea, defending the land.

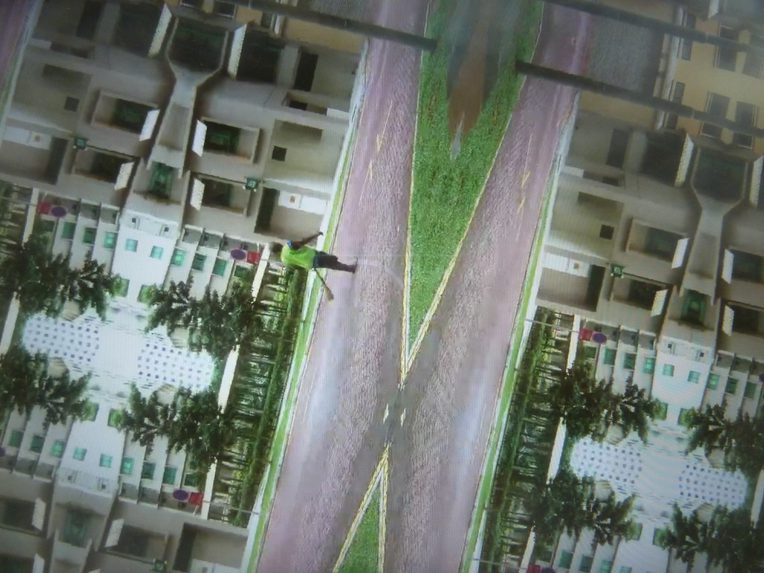

Another recent novel is Daren Goh's (2017) biopolitical meditation, The HDB Murders, a forensic inquiry into the psychological pressure points, and new subjectivities, of Singapore's meritocratic leadership. This new leadership refers to the academically best and brightest, recruited into the bureaucracy and governance of a smart nation, involving artificial intelligence, data mining, face recognition, sensors, and gaming as planning tools of "smart city" infrastructures. The ever-more sophisticated data mining, surveillance, and gaming system to manage governance is a computer or IT system with a name alluding to a drug that heightens concentration and visual acuity, and reduces anxiety, helping to enforce the steady, unflappable, highly rational affect that is de rigueur for the administrative elite. Psychology as well as rationality are perversely manipulated though algorithmically calculated and managed biopolitical equilibria for the good of the nation rather than its individual citizens. As you know, the word meritocracy comes from a famous 1958 book by Michael Young called The Rise of the Meritocracy, which satirized the British Labor Party plans for post-war England, which in turn was a key matrix for the philosophical foundations of modern Singapore (Young 1958). A character in The HDB Murders points out a value of Singapore for the larger global political economy: "As you know Singapore has the most liberal surveillance policy in the world. It lets us monitor anyone in the country without consequences. No questions asked. Mobile phones, emails, video calls, Google searches, text messages. Anything passing through the country’s network. . . . Because of this, many countries . . . use us as an information hub. Through us, they can access all the activity that passes through the undersea fibre optic cables that run below us, which lets them run whatever clandestine operations they want. We’re a search engine for everything that passes through us” (Goh 2017, 190). With this characterization we are back to Charles Lim's undersea fibre optic cables, Margaret Tan's smart aprons, and Sandi Tan's daemons of modern life.

I end with two performance artists who probe deep histories aiming to crack open and fracture the cultural fault lines of xenophobias, ethnic stratifications, and religious extremism. One, with dance and muscle memory, explores cultural styles of person, time, and conduct as they evolve across the Indian Ocean and Malay Archipelago; the other, with music and the construction of rattan ghost ships, aims to teach parents to learn to tell their children their own stories and histories rather than passively allowing all to fade into tall tales and official stories disseminated by the Tourist Board or National Heritage Board. Both provide pressure points, or acupuncture-like therapies for slowing down the world, creating consciousness and mindfulness of the bioecological and sociocultural worlds we inhabit and interact with, opening worlds of sensoria and renewal.

Singapore-born dancer, choreographer, and hatha-vinyasa yoga teacher, Kiran Kumar together with a south Asianist anthropologist travelled down the Kaveri River in Tamilnadu in the 2010s. They stopped at all the little village Shiva temples to seek out traces of ecstatic, tantric dance still surviving from before dance was codified into the "classical" Bharatnatyam and Odissi. And then he went onto Surakarta in Java, where Kumar apprenticed in the slower, more fluid Indonesian alus (genteel, refined) styles (versus kasar, as Geertz and many others have explored) of strength and grace. Kumar choreographs durational sculptures that fluidly and very, very slowly morph meditatively and narratively, requiring exquisitely refined (alus) strength. Across a thin wall, he shares the music and videos loop visuals from his fieldwork journeys. These Archipelago Archives in dance and video, as he calls them, provide therapeutic spaces apart from the high-tech worlds in relation to which they are life lines, and para-sites. They are para-sites or third spaces in being speculative and imaginary translational spaces between India and Indonesia (Fischer 2003); and yet para-ethnographic, in George Marcus's (2000) sense, in being rooted in teaching traditions and temple sites. They are para-sites as well because they provide virtuoso examples for the self-work that has become part of high-tech society's anxiety and emotion therapies.

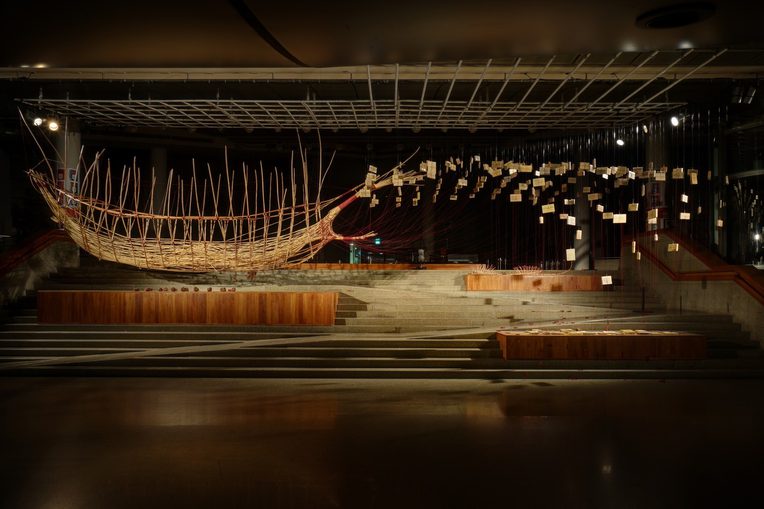

Similarly, Zai Kuning probes acoustic as well as sailing traditions of the "sea peoples" of Southeast Asia. In May 2013, I went to an extraordinary evening he organized of ghazal and asli music in The White House, a colonial wood building on Emily Hill in central Singapore, a venue arts groups could rent. Called Ombak Hitam (Black Wave), the ensemble consisted of his father (a well-known 83-year-old wedding musician), himself (a well-known electronic and experimental music artist, performance artist, sculptor, and painter ), and Tetsu Saitoh (a Japanese double bassist). Kuning would a few years later represent Singapore at the Venice Biennale 2017 with the largest of his ethereally floating Dapunta Hyang ghost ships. The ship was seventeen meters long, made of rattan, red string, and beeswax, and it represented Australonesian, Bugis, Orang Asli, and Sumatran sea voyagers and the knowledges that they carry. The name Ombak Hitam ("dark wave") in Japan refers to the Kuroshio Current that flows north in the Pacific (like the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic), and Tetsu Saitoh uses it as a metaphor for how art and culture travel and mix across the globe. Kuning similarly invokes the seaways of Nusantra (a Sanskrit term revived after World War II in the Malay independence movements, meaning the vast expanse of shallow seas “between the islands” of the Malay "Mediterranean"). In his verbal introduction at the Venice Biennale, Kuning suggested, "Ghazal music has intricate melody, fluidity of movement and notes, the trills of the harmonium and violin whisper about days gone by; while asli indigenous music is percussion-based, mournful, as if pining for decades past. It is a very intimate sound, quite close to talking. We play quietly, trying to talk to everybody," just as from across the waters one hears sound, even loud laughter and raucous play, muffled, quietly “trying to talk to everybody” (my emphasis).

The old wood White House was itself an instrument. Its acoustics were more than acceptable: "The bounce is not so bad as in new buildings, because the walls here are porous and the floor is thick timber. The materials are great for acoustic music as after a few beats there won’t be any more ringing, just a solid clear sound," as Kuning stated at the Venice Biennale. Kuning’s father, the wedding band musician, loved the microphone, but tonight they were not going to use microphones, because “traditional musics, like those played in churches and temples, deal with the acoustics of space and the resonance of sound. We (Ombak Hitam) search for pure sound, sound which is not amplified. It relies on the talent of the artist to control the sound which is not amplified. . . . An audience of sixty or seventy makes the sound quality better. The human body absorbs sound and lessens the echo.”

Kuning has been on a multi-year quest for asli music and mak yong, a folk opera form in the Riau Islands. The quest is part of his sense of guilt for his own ethnic group, the Bugis, who pushed aside the original sea peoples, the orang asli or organg laut, but it is also, more importantly, a pedagogy to counter the forgetfulness of Malays who increasingly conflate Malay with being Muslim, and to counter the fundamentalism and intolerance that can grow on such erasures and singularizations. Recovering submerged histories is not easy, and Kuning’s intuitions about this forgotten richness is supported by evidence that what we think of as Indian cultural transmission eastwards may have been more bi-directional. Malayo-Melanesians were the more adventurous seafarers and might have gone west to get Sanskrit. Not only are the Indian dance poses (karana) portrayed on the Prambanan temple in Java two hundred years before they were carved on temples in South India, but the very form of Borobudur, a Buddhist site in Java, and the form of many Hindu temples in Indonesia and Thailand, are fusions of Australonesian punden (rectangular tiered ancestor mounds to the hyan or ancestors) and Indian cosmograms.

Kuning’s seventeen-meter-long ghost ship for Venice in 2017—like something hauled up from the sea bed of Charles Lim's sonar mapping and visualizations of many shipwrecks along with the fiber optic cables—has wax-embalmed books all around, signifying that the ship is ready to go on a siddhi-yatri, a voyage for blessings and spiritual power (not merely to assert secular sovereignty). The waxed covers of the books are engraved with the Buddhist graphic—lozenge, rhombus, boat, cupped hand, or vulva—signifying life’s rebirths. Portraits of performers of the mak yong and menora dance-dramas of the orang-asli and orang laut (sea people) watch from the Venice Arsenal walls. One even “speaks” via an audio tape. Kuning’s ships represent the seven royal peregrinations or naval circuits of his realm by Paraswarma, the first Malay king. (This is not unlike the seven voyages from the other direction of the Chinese Admiral Zheng He, several centuries later). But they are also part of Kuning’s quest to not lose the stories of the smaller sea peoples, the orang asli (original peoples), orang laut (sea peoples), and orang or urak lavoi (of the coast of Thailand), who he thinks of as having been colonized, oppressed, and nearly exterminated by his own ethnic group, the Bugis, who sent out colonies from Sulawesi across southeast Asia's islands and ports. The Orang Laut today are marginalized, extremely poor fishermen, trying as best they can to live away from the grid, the money economy, and settlements, still mobile in their boats and stilt houses. But once they were warriors, loyal navies for the Sultanates of the area, albeit called pirates by the Europeans. Protectors of the Johor and Riau sultans, they were able to mobilize tens of thousands of fighters on canoes from all over the islands.

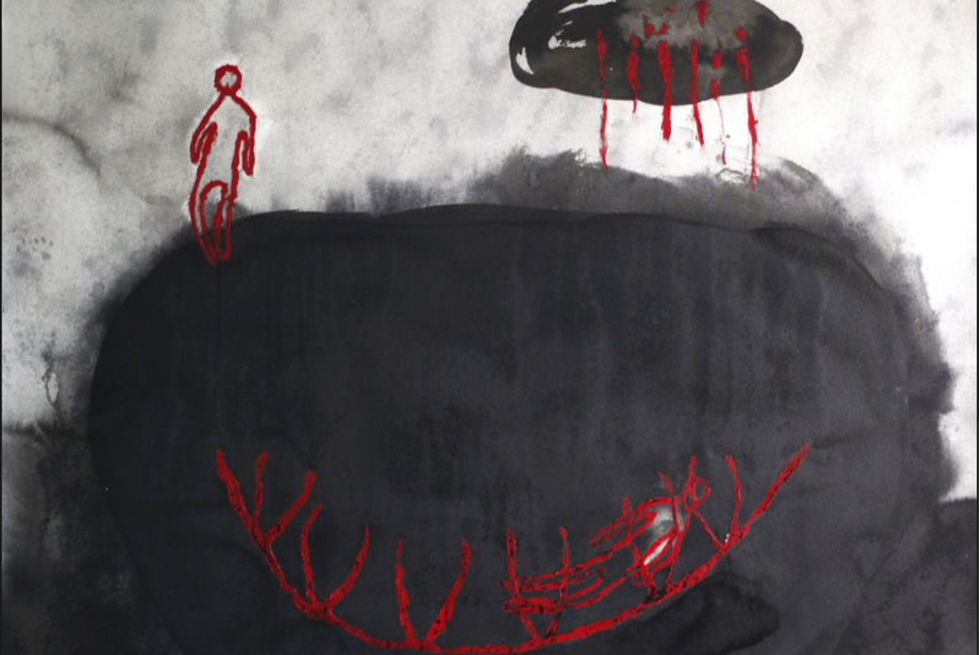

In an earlier installation and performance titled “Loosing Oneself to Be With It and Taken Away by It," presented during the Venice International Performance Art Week in 2014, Kuning appears as a warrior-king infused with spiritual potency, naked to the waist: a body of pure energy (tapasya). Lifted into the air with a knife between his teeth and another in his hand, he hovers over a scarred wood platform, in which two knives and a chopper are impaled. The wood platform merges into a polished steel surface. Slowly the warrior-king lowers himself onto the mirroring steel surface. He ponders his reflected image. It is a striking image, perhaps, of Siddhartha seeing conflict, violence, and the ravages of old age, causing him to turn towards introspection, meditation, and non-violence. Or, alternatively, it is an image of the Bugis warrior, and at times Kuning shows off his knife-throwing skills. While Kuning talks of the displacement of orang laut by Bugis, more generally he blames materialism and modernization for the destruction of feeling at home in the world. At times, he withdraws from urban life to a coastal village in Malaysia where he can re-experience the continuity of sea and land of his boyhood village along the south coast of Singapore, where one can just hop into a sampan and be at home anywhere in the sea and islands. Still at the far end of the installation, there is a small sampan boat suspended with pebbles hanging down pointing at books: the realm of knowledge transmission. Boat and book are metaphors for one another, the shape of one mimicking the engraving on the other.

Kuning and his wife give workshops for children and parents. In an interview with me in 2017, he argued that oral history or storytelling "is not necessarily for the children, it is also for the parents to learn how to tell stories. You have to exercise [this skill]. When I worked with [Kuo] Kao Pun [the playwright and founder of The Substation, where Kuning was the first artist-in-residence] . . . we talked about this a lot, about how we cannot depend on country history, family history, stories based on books, on what the government decides as history, we have to create a certain culture from more story telling. The father did not used to read story books but t[old] stor[ies] about my background, about my grandfather. . . . Personal stories make memories, make the person, the individual, allowing them to become more imaginative, more connected to culture in thinking, so that when they look at something, they can imagine it even more than normal" (my emphasis). How to tell stories is an important mode of stimulating creativity, thinking outside the box of rules and regulations, and finding voice and purpose. "This is what happened to me," is quite different than having a folktale narrated on an iPad or coloring book. It is not just the story, but the telling that is critical, meaning is in its use, and the tenor of the setting is crucial to the source of the spell.

Conclusion: Art as Ethnographic Probes in a Changing World

Dear Cliff,

In pluralizing your title from "Art as a Cultural System" to "Art as Cultural Systems," genres, scripts, and performance forms. And adding to the front the double-edged word "challenging," I have attempted to turn art from the descriptive and ungrounded presuppositional (assuming we know what art is) into the experimental: the probe and even the probative. This is becoming an ever more urgent task in a world of gathering authoritarianisms, corruption, intolerance, and technologies that are reducing the spaces for public moral reason. Both the arts and new modes of ethnography have important parts to play within old and new media. You, too, in "The World in Pieces" challenged political theory as too quickly universalistic and judgmental as I have been challenging philosophy in general and art history here more specifically (Geertz 2000). As João Biehl and Ramah McKay (2012, 212) put it in the context of politics, "ethnography. . . is a form of political critique itself, both in its evidence-making practices and in its descriptive and analytical elaboration."

I have drawn here upon several minor arts in Singapore involving the prosthetic eye, double-conscious gender and media play, and producing talk-stories of re-identification and blocking de-identification by algorithmic manipulation in video, novels, dance, and local musics. I have not turned to theater, the most obvious venue for cultural critique in Singapore, or to thinking about how to counter the hegemonic magic rites of “design and marketing,” which recirculate words and images from popular patter back into branding and selling as modes of motivation and control. The community of Singapore artists, in conversation with their peers locally and elsewhere, attempt to keep alive the implications of the intelligent island and smart nation for the human scale, keeping conversations alive about perverse manipulations of psychology and rationality.

What is needed today is a way to block the speed at which decisions are made in the hegemonic world of “build-test-fail-iterate” until something works at the right price point. This will take a multi-scale rethinking of aesthetics in the world, one that allows for spaces for moral reason to slow down runaway technologies and that builds upon these local human-scale tactics. Such are the social diagnostics, the tenor of the settings, and the sources of their spells for the 2020s.

Note

1. The SCA's editorial use of "personal communications" is reference to interviews and face-to-face conversation taped and transcribed by Michael M. J. Fischer.

References

Biehl, João, and Ramah McKay. 2012. "Ethnography as Political Critique." Anthropological Quarterly 84, no. 4: 1209–27.

Chang, Eileen. 2007. Lust, Caution: The Story. Translated by Julia Lovell. New York: Anchor Books. Originally published in 1979.

Derrida, Jacques. 1994. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International. Translated by Peggy Kamuf. New York: Routledge.

Fischer, Michael M. J. 2003. Emergent Forms of Life and the Anthropological Voice. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

———. 1976. "Art as a Cultural System." MLN 91, no. 6: 1473–99.

———. 1980. Negara: The Theatre State in Nineteenth-Century Bali. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

———. 1988. Works and Lives: The Anthropologist as Author. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

———. 2000. "The World in Pieces: Culture and Politics at the End of the Century." In Available Light: Anthropological Reflections on Philosophical Topics, 218–63. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Goh, Daren. 2017. The HDB Murders. Singapore: Math Paper Press.

Marcus, George E., ed. 2000. Para-Sites: A Casebook Against Cynical Reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tan, Sandi. 2012. The Black Isle. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Wong, Kevin Martens. 2017. Altered Straits. London: Epigram.

Young, Michael. 1958. The Rise of the Meritocracy. London: Thames and Hudson.