Cholas Fighting Political and Visual Struggles

From the Series: The "Marcha a Lima" against the Denial of Modern Political Rights

From the Series: The "Marcha a Lima" against the Denial of Modern Political Rights

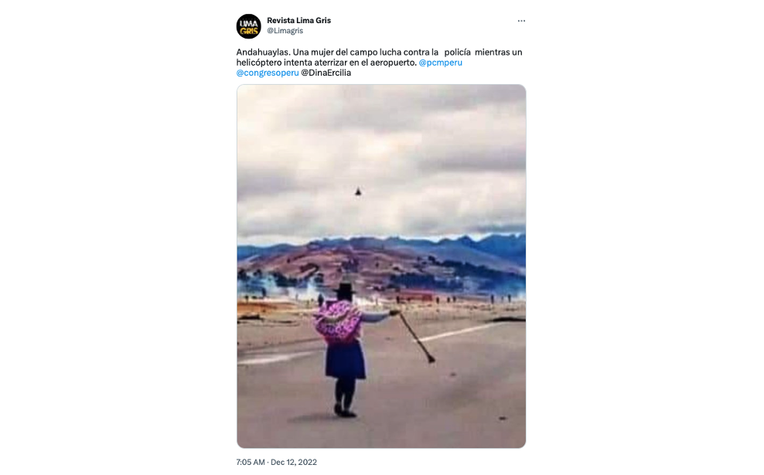

The short clip of a woman wearing traditional Indigenous attire, aiming her huaraca (or slingshot) against a military helicopter, circulated profusely on TikTok and YouTube last December 2022 (Figure 1). It was taken by a witness during one of the protests in the Southern Andean province of Andahuaylas, Apurimac, also one of the first towns to rebel against the interim government of Pedro Castillo’s former vice-president, Dina Boluarte. Other renditions of this image make the confrontation more striking by shortening the distance between the huaraca woman and the machine. They symbolically show people’s material resistance against a murderous state aligned with the equally lethal practices of the economic and financial elites that it represents.

Several other images of Indigenous women at the frontlines of the current social struggle have been reposted nationally and internationally. Women wearing Peruvian flags, mourning our deaths, confronting fully armed police forces, and carrying cardboard pieces on their shoulders cut to look like a map of Peru are a few of the examples. Most of them remain anonymous. Others became public like the case of Aida Aroni Chillcce, who was tortured by the police but promptly released thanks to the public uproar. Here, I want to highlight what seems to be a novel social phenomenon: the empathy, recognition, and pride in celebrating Indigenous women’s strength as part of a shared chola heritage.

A robust historical corpus of research demonstrates women’s continuous defense of life and land during the so-called times of war and peace—that is without question. What has changed is the gaze. While it is true we have also witnessed a myriad of examples of racism since December (a few of them against the aforementioned luchadora Aida), it is also significant how thousands of Peruvians have exalted in their social media the figures of peasant and Indigenous women putting their bodies on the line, traveling for days, taking care of other protesters and their children, cooking, organizing, public speaking, and explaining for national and international audiences the wrongdoings of political and economic oligarchs.

The wealth of the colonial and republican eras could not have been possible without the extraction of labor, sex, reproduction, care, and motherhood from Indigenous, chola, and Black women. I would like to emphasize that this celebration of Indigenous women goes beyond well-worn trends of consumption. What I see here should not so easily be dismissed as fetishizing Indigenous women (though the tension remains apparent), but as the potential of a more hopeful vindication of a shared heritage.

This new possibility of recognizing a shared Indigeneity and chola-ness can be the result of many factors. On the one hand, we have the sustained organizing of grassroots feminist and transfeminist groups that precede the Ni Una Menos marches of 2016; on the other, the mobilization of discourses, research, writing, and visual arts that have, across many contexts and forms, unapologetically entered (and in many ways dominated) contemporary cultural circuits. This recent autonomy from institutions that historically mandated cultural consumption is the result of an arduous self-managing and organizing.

One of the most important contributions of current Peruvian transfeminisms is its direct critique of racism within feminism itself. This critique was never as powerful and as fully articulated as it is today. Yes, there were instances were feminists debated privately and publicly about racial and class differences. For example, working class and migrant women who organized to feed their families and neighbors in the eighties (amidst the crisis of the “internal conflict” between the government and the Shining Path) voiced their multiple discontents. One of the few records of this being the writings of María Elena Moyano, who openly critiqued privilege amongst feminists.

Nowadays, we can read, see, hear, and dance to cholas’ transfeminist work that angrily and joyfully communicate the injustices of racism. This is not just an exaltation to conflict for the sake of conflict. It rather serves to contest, rework, and unsettle what sometimes is our very own deeply internalized self-hate that can take the form of blatant denial, unvoiced acceptance, or simply total indifference to acknowledge our own indigeneity, brownness, and/or Blackness. It is thanks to the violence of this confrontational transfeminism, so sick of racism, that the images of the cholas in the street mean more than an ornamental form of indigeneity.

I met Geraldine Zuasnabar during the two weeks of holiday truce last December in Huancayo. Geraldine is one of the people behind the project Chola Contravisual (Countervisual Chola, or CC) since 2015. The CC journey started in Lima when Geraldine was a provincial huancaína film student in the predominantly white and exclusive, Universidad de Lima. There, they had access to good equipment and a front seat view of the spectacle of high and middle class Limeño sociality. Once their studies were finished, CC relocated to Huancayo to pursue cultural decentralization, cheaper housing, and bluer skies. The transition presented different challenges.

CC operates too from Huancayo and Ayacucho, and it has a wide repertoire of productions, including music videos featuring local and regional musicians, clips documenting feminist protests and gatherings, interviews with travesti folkloric singers, and the YouTube pandemic miniseries “Mejor chola que mal acompañada.”[1]

CC doesn’t limit itself to a denunciation of racism. They are not resentful cholas always concerned about whites, trapped in a grieving loop as one psychoanalyst implied years ago. Chola Contravisual explores notions like radical love (munay in Quechua), erotic justice, and brown and Black jouissance. Geraldine shares with me that the very core of their project is rooted in the life experiences of their mothers and grandmothers, in the oral history, experiential knowledge, drunken excess, frustrations, and again radical love that chola women inhabit. As queer, pansexual, and non-binary cholas they too have to go against this old teaching and create new political languages. Geraldine coins this as “feminismo impuro” in the making of less punitive and more accepting worlds. Amidst this crisis, let's invoke the impure spirit of this transfeminism to illuminate our long-term struggles.

[1] All are available to watch at www.cholacontravisual.com.