Colombia’s 2019 Protests, or How Common Futures Are Imagined through Unexpected Encounters

From the Series: Global Protest Movements in 2019: What Do They Teach Us?

From the Series: Global Protest Movements in 2019: What Do They Teach Us?

Following her coronation in the national beauty pageant, the recently elected Miss Colombia was asked about the protests planned for November 21, 2019. Directing her remarks to President Iván Duque, she stated, “We all protest for a reason, for a cause that unites us.” She went on to call on Duque “to support and listen to the reasons why people protest.” The reactions on social media were overwhelmingly positive. Twitter users expressed satisfaction with the beauty queen by stating “tremenda reina tenemos” (what a beauty queen we have) and “maravilla total” (what a wonder). Considering that beauty queens are prominent public figures in Colombia—thousands of people watch the national beauty pageant that takes place every year in the city of Cartagena on a national holiday—the fact that Miss Colombia openly expressed her ideas about the country’s political situation and encouraged the president to “listen to the reasons why people protest” is unprecedented in the country. Her words not only revealed the growing popular support for the November national protests that opposed a series of neoliberal legislative packages under study by the national government. Miss Colombia’s words also conveyed something else, a central element for understanding what happened in the country that November. This central element, which occupies my reflections in this piece, concerns the hope that was both enabled and challenged by the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC guerrillas signed in 2016.

As stressed by some analysts, the November uprising was a product of—or was at least facilitated by—the peace process, which gave way to a myriad of anxieties and hopes in Colombian society. More than five decades of an internal armed conflict that expanded throughout the country, and that today remains active in numerous regions, have had a profound impact on social mobilization dynamics in Colombia (Archila 2006). One of the most meaningful outcomes of the peace process was that it communicated the idea that armed violence would no longer hinder the public expression of dissent. In other words, the peace process delegitimized armed struggle.

Toward the end of the 1980s and throughout the 1990s, when a series of democratic reforms were passed in Colombia, entire regions witnessed what political scientist Leah Anne Carroll (2011) has described as “counter reform” or a “violent democratization” era. Local elites and emergent paramilitary groups wiped out peasant, community, and rural worker movements that sought to materialize the promises of democratic reform in their localities. In some regions, entire political parties and peasant organizations were annihilated and the survivors were sent into exile (Archila et al. 2002; CNMH 2010). During the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s, guerrilla and paramilitary groups, and counterinsurgent strategies by the state, installed suspicion, fear, and silence not only in regions under armed control, but in the collective imagination of the nation as a whole. In these circumstances, and in a context in which democracy and violent political repression have coexisted for more than half a century (Gutiérrez Sanín 2014), different forms of mobilization have been strictly surveilled and contained by illegal actors and the armed forces in Colombia.

Although multiple forms of collective mobilization remained active during this era, the levels of popular support for the massive mobilizations that erupted on November 21, 2019, throughout the country were unprecedented. The number and diversity of actors that converged on the streets to raise a multiplicity of demands—which I explore in detail in the next section—were unprecedented, too. As I show below, during the November uprising, protesters challenged not only the role of traditional actors such as political parties and unions, but also the spatial dynamics of the protest, its repertoires, and results.

In what follows, I briefly examine the mobilizations that emerged in Colombia in November 2019 by focusing on a series of elements facilitated by an anthropological reading of the events, actors, contexts, and their encounters. I emphasize the idea of a collective social memory activated by the legislative reforms and the context in which they were passed. Through an unusual configuration of the spatial dynamics of the protest and the mobilization repertoires, protesters—particularly young protesters—forged a “shared political temporality” (Bonilla and Rosa 2015, 4) that contested both the legacies of the near past and the expectations of the future. Following the work of Anna Tsing (2015, 28), I suggest thinking the mobilizations in terms of a process of “contaminated diversity” in the making to understand how transformation emerges “through encounter.” I propose considering the unexpected encounters between individual and collective protesters in order to illuminate the configurations of political actors in Colombia’s present context. In response to the usual commentary made by journalists and analysts who ask how the movement will survive or how its tactics and demands will translate into the agendas of political parties, I follow the work of Angela Garcia (2017) in Mexico to consider the November uprising as “something different in the making.” Not knowing what the protests will look like in the future or what tactics will prove more effective is not an issue. What mattered was the encounter, the contamination.

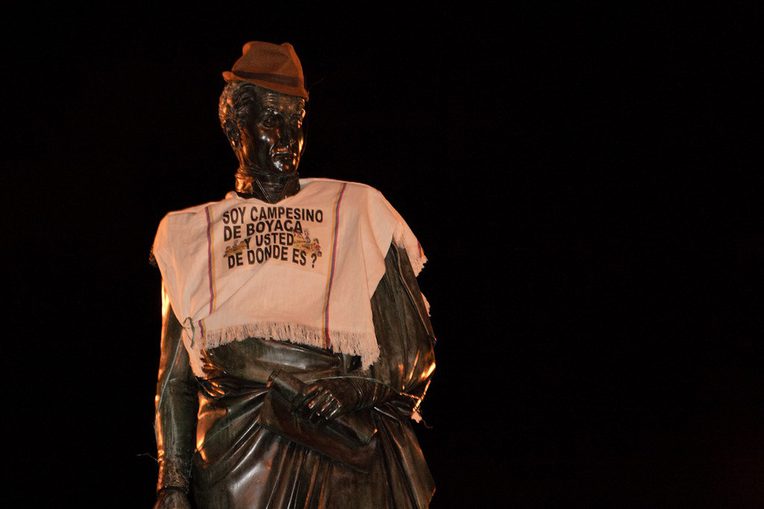

Weeks before the national mobilization in November, labor unions expressed their opposition to a series of neoliberal pension and tax reforms under study by the government of President Duque. Notably, a reform that would introduce a minimum wage slash to young workers received the strongest criticism. Protesters called it “el paquetazo de Duque” (Duque’s legislative package). Although Duque’s cabinet was merely contemplating the reforms—as government officials rushed to declare publicly—unions and allied sectors knew the harm that the proposed changes would cause, particularly on fresh-out-of-college workers. Rejecting el paquetazo thus designated the first visible set of demands that, in a matter of days, congregated in protest a multiplicity of actors such as students’ groups, feminists, LGBT collectives, rural workers, and Indigenous and Afro-Colombian organizations, among others. Both the legislative reforms themselves and the context in which they emerged activated a social memory and opened a crack that protesters felt compelled to expand through their mobilization practices, as I describe in this section.

Although the rejection of el paquetazo initially channeled frustrations and hopes for change, things soon proved far more intricate. The rate of disapproval of Duque’s government peaked at 69 percent

only a year after he took office (October 2019). His public effort to “revise” the peace agreement was seen by diverse social sectors as an attempt to undermine the peace process by refraining from working on the implementation of the peace accords. Duque’s disdain for the peace process translated into a growing sense that things were deteriorating. Particularly salient were voices of despair that came from zones where violence is still rampant. The massacres and public exposure of dead bodies that have occurred in the last couple of years revived trauma in large segments of the population, particularly rural residents, and indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities (Human Rights Watch 2019; Revista Semana 2019), which drove the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC) to declare a state of Humanitarian Emergency for all indigenous groups on August 9, 2019 (ONIC 2019).

One of the most distressing signs of the country’s current moment is the massive killing of social activists and former FARC combatants that began to occur even before the formal launch of the peace agreement—under the government of President José Manuel Santos. From January 2016 to July 2020, 307 social leaders and human right defenders were murdered in a pervasive politics of extermination that has continued during the Covid-19 pandemic. Misguided decisions regarding the eradication of coca crops and military tactics for dismantling FARC dissident structures led to the resignation of Duque’s Minister of Defense days before his Senate impeachment. This was motivated by the bombardment of a high-rank FARC dissident by the armed forces on August 3, 2019, which resulted in the murder of at least eight minors. This event produced profound outrage, particularly among those who feared the return of the war tactics and disproportionate military action that characterized the Colombian government’s response to the armed conflict between 2002 and 2012, during president Álvaro Uribe’s term.

This sentiment of pessimism emerged amid a favorable climate for protesting. Not only did massive protests in neighboring countries fuel generalized feelings of hope for transformation, but also previous experiences in the country had a vital influence in the November protests. I suggest that we cannot understand what happened in Colombia without first considering those recent past experiences that paved the way for the November uprising. Toward the end of 2018, students from public and private universities held nationwide protests denouncing the funding crisis of higher education. On March 10, 2019, the Indigenous National Minga protested the deterioration of the lives and communal projects of Indigenous communities that inhabit southwest Colombia, blocking the Pan-American highway that connects the center with the south of the country. Days later, on March 18, thousands marched in different cities against a series of modifications to the statutes of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace proposed by Duque’s cabinet, which would have undercut the transitional penal system’s ability to judge the atrocities committed during the armed conflict. These mobilizations, and the November uprising, in turn, expanded and revisited the repertories, demands, and agreements of past national mobilizations, such as the students’ mobilizations organized by the Mesa Amplia Nacional Estudiantil–MANE in 2011–2013; the National Agricultural Strike (Paro Nacional Agrario) in 2013; and the Pacific Regional Strike (Paro Regional del Pacífico) in 2017.

More important, however, was the climate created by the peace process. The November 2019 mobilizations cannot be understood without first considering that the peace agreement enabled hope and new figurations of the political imagination in Colombia. As mentioned by one of my friends who participated in the mobilizations, “the peace process opened up a crack through which we felt able to express political dissent without the same fear of being killed that we had before” (personal communication, May 2020). It is in this context that I suggest thinking in terms of a social memory that previous experiences of mobilization and el paquetazo activated—this is the “crack,” which protesters then expanded. The peace accords granted an unprecedented opportunity to imagine political dissent in other terms, and that opportunity demanded to be protected. Protesters, and particularly young protesters, rejected the expectation of a post-peace agreement future defined by the growth of inequality and the return of war tactics. In this sense, the mobilizations exceeded the tax, labor, and pension reforms. Protesters were reclaiming their right to dissent as a means to imagine other futures.

One of the most telling facts of the November mobilizations was the massive participation of diverse sectors, some of which converged in the protests for the first time. Feminist and LGBT groups, organizations of victims of the armed conflict, and young people joined labor unions, students, and Indigenous, rural, and Afro-Colombian organizations. During the November uprising, the majority of protesters did not feel represented by traditional mobilization actors such as political parties and labor unions (Calderón 2020). In fact, relative to previous mobilizations, political parties played a minor role in the organization and unfolding of the protests. Conversely, the role of student groups and other youth protesters was crucial. As mentioned by another friend, “young people sustained the mobilization” (personal communication, May 2020).

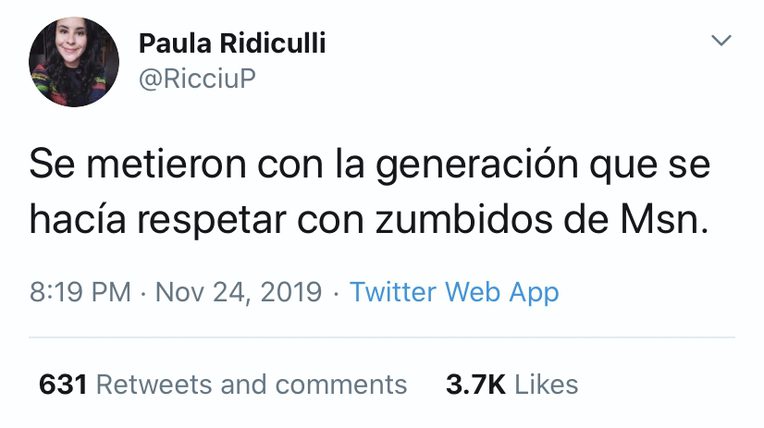

In a post-peace agreement era, young protesters demanded a different configuration of the future. They situated themselves as a generation that is contesting the continuation of neoliberal policies and the return of war tactics, such as the bombardment in which at least eight minors were murdered mentioned above. The post-conflict future, as elusive as it seems at this point in the country, enabled and challenged forms of political imagination. Social media rapidly saw the circulation of numerous posts expressing this young generation’s lack of fear and their willingness to protest. Many of these posts played with the idea that young protesters belonged to a particular cohort that grew up watching certain TV shows, playing certain music, and meeting new people through digital platforms, all of which serves to explain their lack of fear and determination. The now well-known line, “They are messing with the generation that __,” followed by, “We are not afraid,” “Resistance,” or “They can’t hide anything from us,” circulated as an imaginative means to convey young people’s support for the protest while expressing their demands and expectations.

For their part, women and feminist groups throughout the country denounced violence against women, particularly against social activists in rural areas, as well as the continuous setbacks in access to women’s reproductive rights. Together with other actors, women and feminist organizations marched on November 25 celebrating both the day for the elimination of violence against women and the continuation of the national protests (Gaitán Mateus 2019). LGBT groups, additionally, denounced Duque’s lack of political will to advance public policy centered on LGBT lives (Caribe Afirmativo 2019).

These social actors not only met in the main streets of the capital city of Bogotá. The spatial structure of the protests in the city follows a well-known route that begins in a couple of different points of the city to cross some of the busiest streets. Protesters then converge and march through Seventh Avenue to end in Bolivar Square, a place surrounded by Congress, the Presidential House, the Mayor’s Office, and the Palace of Justice. This time, however, the protests defied this spatial dynamic. On November 21 and the following months, diverse social actors met at points throughout the city other than the main streets. Beyond the widely documented massive mobilization of November 21, protests that continued during the following months followed a polycentric structure that located protests at the neighborhood level. As a testament to this new spatial structure for the November 2019 protests, following the first day of protests and in response to police brutality and a curfew announced only a few hours before it came into force, protesters in Bogotá and other cities gathered to perform a cacerolazo in their neighborhoods. The cacerolazo, a common repertoire throughout Latin America, refers to making noise by banging pans and remains today one of the symbols of the November uprising. Spontaneously, hundreds of protesters gathered in central locations within their neighborhoods to sing, dance, and, in some instances, discuss their demands in assemblies. Inadvertently, as a friend explained, such local assemblies and gatherings expanded and gave substance to the demands that initially congregated the protesters. As my friend conveyed, people debated about pressing issues that they experienced in their daily lives, such as the local economy and access to basic public services, among others (personal communication, May 2020).

The numerous posts on social media and the neighborhood cacerolazos forged what Yarimar Bonilla and Jonathan Rosa (2015) have called a “shared political temporality” in reference to the wide circulation of news and commentary through social media, particularly Twitter, that followed the police shooting of Michael Brown in 2014 in the United States. In the case of Bogotá, a shared political temporality emerged as people posted about the protest on their social media accounts and as they encountered each other during neighborhood cacerolazos. Through these operations, protesters that were physically distant felt that they inhabited a simultaneous temporality materialized in their demands, twits, and chants. What do these encounters and configurations of time and space tell us about the protests? How can we think about these encounters and the unexpected results that emerged?

When thinking about the possibilities of life that emerge from ruins, Tsing (2015, 29) introduces the idea of contaminated diversity to as a form of “transformation through encounter.” I suggest thinking about the November uprising through this lens. For Tsing (2015, 28), “We are contaminated by our encounters; they change who we are as we make way for others. As contamination changes world-making projects, mutual worlds—and new directions—may emerge.” Inheritors of the anxieties introduced by the strict racial and class taxonomies of the colonial era and decades of violent suppression of dissent, protestors converged on the streets defying the spatial and temporal structures of protest in the country. It is in this sense that framing the protests in terms of contamination entails a political move and an analytical opportunity. In other words, contaminated diversity questions the individual or collective self-contained subject at the same time that it refuses the idea of an amorphous mass that should converge around a limited set of motives. Contamination is at ease with the multiplicity of agendas, the long-term nature of the demands, and the contradictions therein. The contaminated encounters and the subjects-in-the-making in Colombia’s protests are the unexpected results of exchanges that occurred and are still occurring, for instance, between union leaders and young protesters, between Indigenous and LGBT organizations, and across the sounds and voices that emerged from the balconies during the cacerolazos.

Anthropological attention to the rhythms and nuances of mobilizations also invites a critical examination of the common question posed primarily by political analysts who ask whether the movement will survive or result in a formal political agenda (Dávila 2019). Following Garcia’s (2017, 113) work, I suggest thinking about the November uprising as “a moment of rupture that expresses the presence of something different in the making.” To the question often posed to protesters of what comes next, the answer is not necessarily clear. And it does not need to be so. Uncertainty in this context is not an issue. The mobilization was the encounter, and the encounter was the unexpected result. There are multiple possible answers about the future—as many as there are protesters banging their pots on the streets and their balconies. Protesters do not know for sure how the future will look, but what they do know is that it needs to be different.

Archila, Mauricio. 2006. “Los movimientos sociales y las paradojas de la democracia en Colombia.” Revista Controversia 186: 9–32.

Archila, Mauricio, Álvaro Delgado, Martha Cecilia García, and Esmeralda Prada. 2002. 25 años de luchas sociales en Colombia, 1975–2000. Bogotá, Colombia: CINEP.

Bonilla, Yarimar, and Jonathan Rosa. 2015. “#Ferguson: Digital Protest, Hashtag Ethnography, and the Racial Politics of Social Media in the United States.” American Ethnologist 42, no. 1: 4–17.

Calderón, Ómer. 2020. “Sindicalismo y movilización social: Una relación complicada.” Revista Razón Púbica, February 24.

Caribe Afirmativo. 2019. “¡Todxs Paramos!” Corporación Caribe Afirmativo, November 15.

Carroll, Leah Anne. 2011. Violent Democratization: Social Movements, Elites, and Politics in Colombia’s Rural War Zones, 1984–2008. Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press.

CNMH (Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica). 2010. Silenciar la democracia: Las masacres de Remedios y Segovia, 1982–1997. Bogotá, Colombia: CNMH.

Dávila, Andrés. 2019. “Implicaciones, efectos y perspectivas del 21N.” Revista Razón Pública, November 25.

Gaitán Mateus, Lina. 2019. “Ninguna lucha vale más que otra: las mujeres en el paro.” Pares – Fundación Paz y Reconciliación, December 16.

Garcia, Angela. 2017. “Heaven.” In Unfinished: The Anthropology of Becoming, edited by João Biehl and Peter Locke, 111–132. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Gutiérrez Sanín, Francisco. 2014. El orangután con sacoleva: Cien años de democracia y represión en Colombia (1910–2010). Bogotá, Colombia: Debate and Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Human Rights Watch. 2019. “The War in Catatumbo: Abuses by Armed Groups Against Civilians Including Venezuelan Exiles in Northeastern Colombia.” Human Rights Watch, August 8.

ONIC (National Indigenous Organization of Colombia). 2019. “ONIC alerta y denuncia grave situación de derechos humanos que atraviesan los pueblos indígenas del norte del Cauca.” ONIC, August 10.

Revista Semana. 2019. “Tumaco, la suma de todos los miedos.” Semana Rural, March 17.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.