Good Friday liturgical services in the Armenian Apostolic Church—under normal circumstances—include a grand procession carrying a wooden recreation of the Tomb of Christ. In the Christian Gospel narratives, Good Friday is the darkest day of Jesus Christ’s earthly ministry as Jesus is condemned to death, mocked, crucified, and buried. Christians of all denominations recall that darkest of days, albeit it with an important difference: Christian certainty in the Glorious Resurrection on Easter Sunday. The pinnacle of the Christian year and the telos of Christ’s earthly ministry, Easter Sunday is the celebration of Christ’s “trampling down death by death” as an Orthodox hymn poetically proclaims. Resurrection Sunday and the promise of eternal life is made even brighter by the darkness of Good Friday. For liturgically grounded churches like the Eastern Orthodox or the Armenian Apostolic, one of the ancient Christian churches that are together known as the Oriental Orthodox Churches, that heightened theological experience can only be secured through liturgical participation: keeping the Holy Thursday vigil, processing with the tomb on Good Friday, and finally, receiving Holy Communion on Easter Sunday.

What then, in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic forcing people to remain at home, could the experience of Easter and all of Holy Week preceding it have been for such liturgically dependent Christian denominations? What can liturgy and its quintessential activity of Holy Communion look like under quarantine? The specter of “packed churches” and pastors flouting stay-at-home orders on Easter in mid-April 2020 received a decent amount of media attention, though most Christians followed social distancing guidelines. However, for the “high liturgical churches” like the Oriental Orthodox Churches, including Coptic and Syriac Christians, as well as the Armenian Apostolic Church that I study and in which I serve as a deacon, it is not simply an inability to gather with loved ones that causes concern.

As Talal Asad (2003, 205) has carefully argued, “the modern idea of a secular society included a distinctive relation between state law and personal morality, such that religion became essentially a matter of (private) belief.” Others have followed him in describing how Protestant Christianity, with its emphasis on sola scriptura and a personal relationship with God, functions fairly well with an understanding of religion as non-coercible interior private belief. While Christians of all denominations bemoan the inability to come together to celebrate the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, the consequences of that inability are not uniformly felt. If one’s Christianity is primarily an interior belief, with Sunday services as a chance to be together with fellow believers, to be edified, and to reinforce one’s private belief, there is no fundamental problem with, say, a livestreamed service. Indeed, many evangelical “mega-churches” have long been mediated through screens, broadcasting for either on-site worship in a packed house or for television viewing.

For others, though, like Armenian Orthodox Christians, for whom liturgy is not merely a gathering of individual believers but an active partaking in Holy Communion that therefore stitches together the Church as such, there are fundamental theological concerns over the inability to physically come together for robust sacramental life. On the academic blog of Fordham University’s Orthodox Christian Studies Center, Public Orthodoxy, Orthodox clergymen, theologians, and scholars have unraveled these concerns. Some have gone so far as to suggest that without collective coming together in liturgy to partake of Holy Communion as the Body of the Christ, the Church (also understood as the Body of Christ) is at best a shadow of itself. The essential ecclesial reality of a liturgical church like the Eastern Orthodox or Armenian Apostolic therefore comes into question. Mass participation in Holy Communion and other liturgical services this Holy Week, however, was not possible.

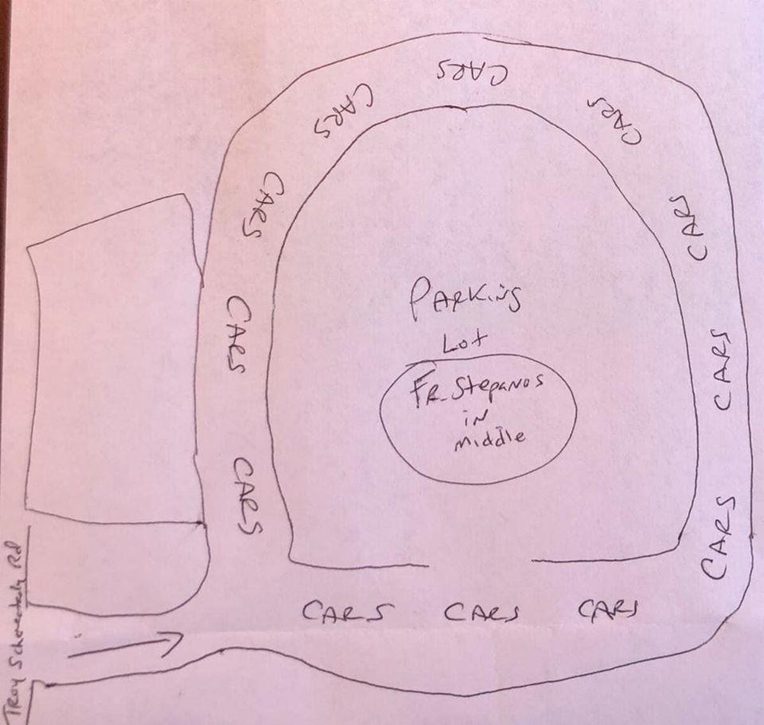

What, then, did “Communion in Quarantine” look like? The question, as I have suggested, was not merely academic, but foundational to the understanding of what it means to be an Armenian Apostolic Christian. A group of three clergymen recognized this and met for “Communion in Quarantine” via YouTube. In a short intensive course on the “Anthropology of Religion for Christian Leaders” that I taught—remotely—two weeks before Holy Week for the St. Nersess Armenian Seminary, seminarians and clergymen joined me on Zoom, discussing the possibility of distributing Holy Communion door-to-door and arguing about whether or not livestreamed, reduced services with a priest, deacon, and cantor would cut it. Many of the same clergymen who joined me in this debate went on to develop creative liturgical solutions for Holy Week and Easter. One priest imaginatively adapted the traditional Antasdan “Blessing of the Fields” service for the age of social distancing: he and a deacon, after celebrating Easter Mass, went into the parking lot and conducted the service, surrounded by thirty cars each six feet apart. The night before the service he posted a diagram to his Facebook page describing how it would work. Armenian Orthodox Christians were not alone in the move to creative remote worship: other Oriental Orthodox Churches, including cathedral churches in Cairo and Addis Ababa, held such services.

On Good Friday, while there were no elaborate processions, the St. Nersess Armenian Seminary in New York, where I teach as an adjunct faculty, orchestrated a remarkable solution. Via Zoom—as so much of life occurs these days—faculty, students, and friends called in from as far-flung places as London. The lone resident deacon and priest worshipped from the small chapel, while the rest of us were assigned readings, chants, and hymns. Piece by piece, we put the building blocks of liturgy into place. It was not physical presence, but it was active participation in the traditional Crucifixion service. At the end of the service, Bishop Daniel Findikyan of the Eastern Diocese of the Armenian Church of America and member of the St. Nersess faculty reiterated that Good Friday is in fact the darkest day of the Christian year. Almost inevitably, he noted, it seems to be an overcast day. As I looked outside the window at the April snowstorm that had swept in after days of unseasonably warm weather, the Bishop insisted that for Christians the dark day of Good Friday always comes with the hope of the Resurrection on Easter. Though the ecclesial conundrums continue, for Armenian Apostolic Christians, alongside all Christians with a strong liturgical tradition, Holy Week and Easter has gone on in the midst of the pandemic, albeit with ad hoc, imaginative alternative liturgical celebrations.

References

Asad, Talal. 2003. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.