Conversations in Plaza Manco Cápac: On Police Violence in the Government of Dina Boluarte

From the Series: The "Marcha a Lima" against the Denial of Modern Political Rights

From the Series: The "Marcha a Lima" against the Denial of Modern Political Rights

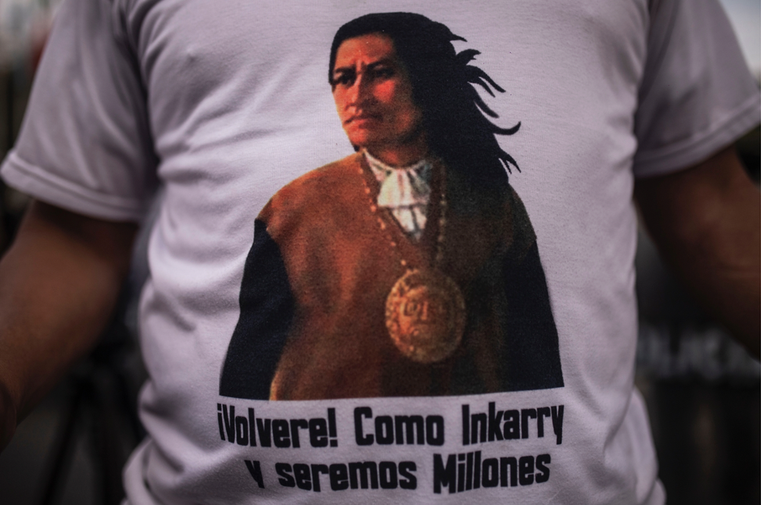

There must be about 400 people camping in Plaza Manco Cápac (downtown Lima). Several were delegaciones from the southern Andean villages, that had traveled to add to the massive number of demonstrators arriving in Lima from all over Peru to make their demands heard. The plaza is covered with nylon tents, mattresses, Tawantinsuyo flags, cardboard coffins with the names of those killed during the protests, banners demanding a new constitution, the closure of the Congress and the resignation of President Dina Boluarte. A man speaks in Quechua to about twenty people, showing them a banner where the recently ousted President Pedro Castillo rides a white horse next to Inca Pachacútec. A group of etnocaceristas reservists—soldiers and former soldiers with a nationalist ideology that promotes the supremacy of the Indigenous race—do military exercises. Some women prepare an olla común (collective meal). One of them tunes her radio to the huayno Piedra tirada en el camino by a singer-songwriter from Ayacucho, Manuelcha Prado. The police gather at various points around the plaza watching the protesters in tense calm.

In this piece, I think about police violence in the protests against the government of Dina Boluarte through the conversations I had with people gathered in the plaza and with an activist friend. I also talk with my dead father. A grassroots organizer part of his life, he was born in an Andean community; he was still alive when I was a college student and we often talked about state violence as I moved between fieldwork in Andean communities and protests against the dictatorship of Alberto Fujimori. Conversations with my father happened in my head and are evocative of that period. These conversations accompany this essay in italics and bold.

The photographer Juan Zapata, who allowed me to use his pictures of the protests in Lima and captioned them is also a voice in this piece.

January 1, 2023. I approach a group of people whose clothes indicate they may come from Cusco. I greet them, tell them I live abroad, and ask how I can support the delegaciones. They invite me to sit with them. A woman tells me they are fine, that some Limeños, “poor people like us,” gave them “food, blankets, and even mattresses.”

A man passes around a bag of coca leaves. I grab some leaves and pijcho (chew coca) with them. The woman tells me laughing: “So, you’re not a terna! The ternas don’t know how to pijchar.”

Ternas are members of a squad of plainclothes policemen trained to infiltrate protests to incite violence, plant evidence, and carry out arbitrary arrests. They also gather information for uniformed officers.

I ask the woman if there are ternas in the plaza and she discretely points to a man in sportswear and dark glasses. She saw him talking with three policemen outside the plaza just before they arrested a “community leader who knew how to talk to the people.”

The police act as a dispersed body (Das 2022), a disciplinary dispositive that enables control to flow at the capillary level through, for instance, the listening practices of the terna and the arbitrary arrests; police do not only watch from outside, they permeate the plaza.

January 2, 2023. Endless lines of policemen have blocked the streets surrounding the plaza. I am with a friend, an activist, who, with indignation and outrage combined, tells me that delegaciones are being evicted. We try many different streets to get to the plaza. “There’re so many policemen!” she says, pointing at the scarves that some of them are wearing. The scarves, she explains, are meant to shield them from tear gas. To her, they are a sign that the police plan to “gas” protesters.

A woman with a Peruvian flag approaches a line of policemen. She tells them they share origins, they could be her own children, why are they shooting their own people? “Let’s leave,” says my friend. The policemen may feel provoked by the woman and start shooting tear gas or pellets.

The dispersed body of the police is marked by signs, though these might be unclear to many: the relative number of officers, where they are placed, what they are wearing. My friend can read these signs: the possibility of violence is imminent. And she was right.

That night the news programs show images of policemen shoving people out of their tents as they tear them apart. A voiceover triumphantly declares that the police managed to “recover” the “historic and emblematic Plaza Manco Cápac” from “vandalic violence” of the protesters. Perhaps it was again the dispersed body of the police providing this reading of events to the newsrooms I thought as I watched the protestors in the background of those same images struggle to rescue their belongings.

January 3, 2023. The plaza is almost empty. There are police pickets on every corner, a few scattered people, and no material traces of the hundreds who were here yesterday.

Some of us walk toward a young man beginning a speech: “We’ve come here to Lima, the nobodies, the second-class citizens, those used to lower[ing] our heads. We have been called terrorists, and our word is worthless, our demands aren’t heard.” The audience applauds him: “We’re tired of being terruqueados and having our voice silenced. Without a voice we’re not people, turned into animals, and the police kill us.”

Someone begins to chant, “we’re not terrorists, we’re citizens.”

In Peru, the opposition between terrorist and citizen grounds terruqueo, a practice that uses unfounded accusations of terrorism to stigmatize and criminalize protesters when they are people racialized as Indigenous and peasants. As a colonial/modern tool, it strips people of voice and denies their capacity to make demands, placing them in what Franz Fanon (1952) calls a “zone of non-being.” Terruqueo turns people into killable beings—animals, as the speaker says at the plaza.

In this extraordinarily barren zone, only a convulsion can produce new conditions of existence. The man finishes his speech: “The time has come to raise our heads and build a big homeland where there is room for all of us.” Although what is happening is already cataclysm, its impact on the order of things remains still unclear.

Das, Veena. 2022. Slum Acts. London: Wiley.

Fanon, Frantz. 2008 [1952]. Black Skin, White Masks. London: Pluto Press.