Editors’ Introduction

In 2010, a conversation was ignited over incorporating photo essays into the new Cultural Anthropology website. The conversation, which started about a photo essay project, quickly transformed into a discussion about disciplinary boundaries, peer review, and new directions in anthropology. With the understanding that so many anthropologists are engaged in alternative forms of critical ethnographic expression and thought came the realization that it was time for renewed discussion about content and aesthetics as well as procedure and review.

It is with great pleasure, then, that we introduce our first photo essay, by Daniel Hoffman. In this inaugural essay our goal was to present an aesthetically and intellectually powerful piece of work and to spur provocative conversation. Our goal was to facilitate a conversation about the medium and the message; to do so, we felt we needed to press the boundaries and ask our contributor and reviewers to reset the stage of peer review. They all graciously agreed to do so. The result is that we have a stunning essay presented with “open” peer reviews.

By choosing an open peer review process we mean to perform a critical engagement with the photos, while also instigating a discussion between author and reviewers, as well as author, reviewers, and audience. This would produce a different reviewing and viewing process while facilitating new conversations about ethnography and representation. It would also be to further ask: What is the intent of peer review? And what can we do differently with this process (and this medium)? Our two reviewers, Zeynep Gürsel and Alan Klima, generously agreed to have their comments made public in service of starting the dialogue.

We believe this first photo essay sets a high bar for the potentialities of visual anthropology. Our hope is that it will lead to further discussions: on photography, the role of art and media in anthropology, and also the process and practice of peer review for these representative modes of ethnographic work. It is meant to be an invitation and a provocation. While future photo essays will not necessarily engage in an open peer review process, we hope to continue a dialogue about the practice of visual anthropology and what counts as scholarly practice.

Michelle Stewart and Vivian Choi

Download “Corpus: Mining the Border” by Daniel Hoffman as a pdf booklet.

Photo Essay

So I resolved to start my inquiry with no more than a few photographs . . . Nothing to do with a corpus: just some bodies.

–Roland Barthes

Mayengema

The sounds on the mines around Mayengema are scratchy, percussive sounds. Sounds of scraping, shaking and digging. These are sounds of destruction. Over them float the voices of miners and bosses. Male voices, sometimes singing, but more often bantering, arguing, or cursing. The diamonds they search for make no sounds that distinguish them from the gravel, mud, and water of the mine.

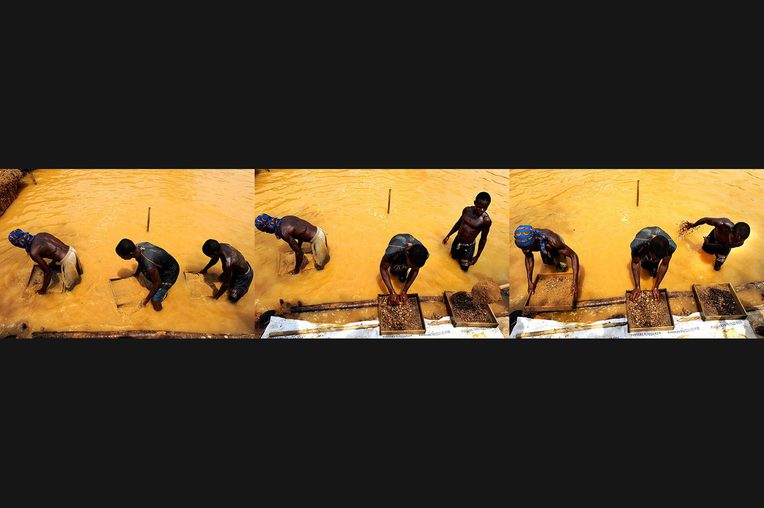

The Mayengema mines seem somehow to exist in a low visual register as well. The mud of the rainforest floor and the dense vegetation that surround the pits are monochrome yellows and greens. The tools of alluvial or surface mining are spare and symmetrical: hand shovels, troughs and screens. Gravel from the bottom of the pits is maddeningly uniform. The bodies of the miners are stripped to their essence by hard repetitive work and the hard repetitive landscape.

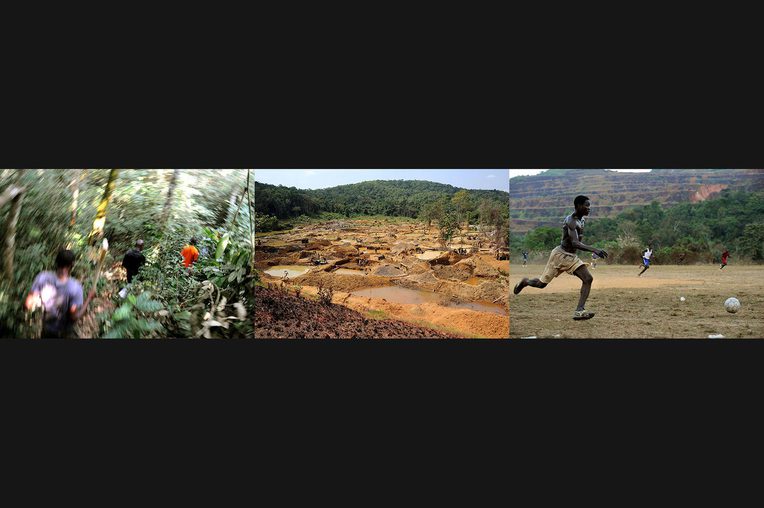

The village of Mayengema lies on the Moro River near the Sierra Leone–Liberia border. It is some fifteen miles from the nearest road, which is itself only passable in the dry season and then only by motorbike. The cataracts on the Moro River make it impassable by boat, so what comes and goes from Mayengema comes and goes by foot.

In the past two years thousands of young men have made the trip to Mayengema and to other small settlements throughout the Gola Forest. The more established and accessible diamond fields to the north and west have become crowded and dangerous. The rapaciousness with which they were mined during Sierra Leone’s war has convinced many that the fields are virtually tapped out. Too many authorities claim ownership over the sites, and there is close scrutiny of who goes in and what comes out. These Gola Forest deposits, by contrast, are harder to access and thus potentially more rewarding. They hold the promise of virgin territory and less competition for young men willing or desperate enough to leave everything else behind.

Much of the mining workforce in the forest pits is made up of ex-combatants from fighting factions on both sides of the border. Fighters I knew from Sierra Leone’s Civil Defense Force and from Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy followed the rumors of rich new diamond deposits ever deeper into the forest. Along with their former adversaries from the Sierra Leone army, the Revolutionary United Front and the National Patriotic Front of Liberia they moved in small groups of two to a dozen. Often these same units fought together during the war; then as now they blur the distinction between a labor crew and a militia squad. For two decades and more many of these men have cycled through the region’s urban and rural battle zones, political campaigns, and gold and diamond mines. They follow rumors of work or are sent on the orders of patrons with the authority to control their labor. They transit networks of friends and contacts and rarely remain situated long. They arrive and depart as strangers.

In early 2010 I visited Mayengema and other borderland mining sites as part of an ongoing ethnography of the mobilization and militancy of young men’s labor in Sierra Leone and Liberia. Much of my research charts the ways in which this particular West African warscape is organized around the efficient assembly and deployment of young men and their physical capacities, especially their capacity for violence (see Hoffman 2007a, 2011a, 2011b). It is a political economy that has reshaped the meanings of patrimonialism and military command, and reshaped the meanings of youth and male sociality. It is a political economy that refigures the very spaces of the city and the occult imaginary. What has been striking is the interchangeability of spheres of work, the qualitative similarity for many young men between the tasks and rewards of war fighting and the tasks and rewards of mining, campaigning, or tapping rubber. Having elsewhere explored the macro processes that made these young men available to forces larger than themselves, I came to Mayengema and the Gola Forest to chart these processes at the level of the material bodies of young men. The resulting photo essay is an ethnographic portrait of the shape and texture of work.

Labors of the Body

Work on the mines is sisyphean. Diamonds are carried across this landscape by century after century of moving water and shifting earth. One accesses them by panning creeks and river floors or by scrapping away the topsoil. The first step, then, is to alter the earth: divert the course of waterways if possible, or peel back two, ten or twenty feet of the forest floor. This is deconstructive labor measured by the shovelful. Mining plots are made by transforming the forest into a clear-cut moonscape, pit after pit separated by towering piles of discarded earth, sand and stone, all dug by hand.

The exposed sand and gravel must then be washed and sifted. The pits are flooded. Hand held screens allow the miners to pass dirt and water through, trapping larger objects at the top. Next the centripetal forces of rapid rotation separate generic stones from the heavier diamonds. The miners stand in the flooded pits or flowing waterways and they bend and sift for hours while a comrade loads shovel after shovel of sand and gravel. The miner shakes his screen, running his hands through the top course of stone left on the sifter and tossing the lighter, worthless stones back into the pit. Once a volume of heavier stone has settled on the bottom of the sifter, he and the rest of the crew will gather. Together they carefully pick through the small pile, looking for oddly shaped and colored bits of wealth amid the debris.

The work is always hot and always hard. As the number of pits grows and the forest canopy disappears the miners place palm fronds around the pit to make shade. In the dry season the bodies of the workers are parched from the waist up, water logged from the waist down, but the work goes quickly. In the long wet season everything is soaked and much of what the miners’ shovels pull out the rainwater immediately puts back in.

When the small pile does unearth stones of value, these stones begin to traverse a complex and varied web of relations. Much depends on the arrangements that brought the miners here and on the personalities and predilections of everyone involved. Typically, the crew has a boss. He might be slightly older than the other miners, perhaps once a low-level commander at the battlefront or a team captain on the campaign trail. In some cases he is entirely beholden to a patron, a more powerful figure who pays for the crews’ equipment and transport to the mines and who provides them with a single, simple meal a day. In some cases the crew boss himself acts as patron, though the fact that he is here in the muddy pits means he is not wealthy enough to deploy the labors of others.

Through the boss the crew is bound to other links in this chain. These include the landowner holding title over the plot, the local representative of the Ministry of Mines, the holder of the mining permit, who may or may not be the landowner and may or may not be the patron and may or may not be the crew boss. Every one of these is a stakeholder in the operation and ultimately in the small pile of stone. Depending on their level of trust in one another and the quality of the gem, they might all go together to a makeshift diamond purchase office in the village or town closest to the mine. They might travel collectively to Zimmi or Kenema, towns with multiple buyers and higher prices. If the level of trust is high or the crew is inexperienced or can’t afford the trip to town, the boss might simply sell the stone to his patron for a fraction of its value. Periodically a miner or an entire crew will slip away in the night, leaving everyone to suspect that something of real value was pulled from the ground and the diamond is headed for Freetown or Monrovia, the miners having made the calculus of risk and reward and decided in favor of flight.

Many of the thousands of miners who have moved into this forest live at the pits in makeshift camps. They supplement the meager provisions of their patrons with what they can glean from the forest or barter from nearby villages. Others pack tight in the small huts of forest communities, paying a minimal rent that is often transacted in labor rather than cash. There are larger towns at the edge of the forest, towns like Mano River Kongo on the Liberia side that are close enough to the forest pits that the men travel there and back daily, though this means long treks on difficult forest paths. These towns are swollen with men. For Mano River Kongo it is not the first time. This was once a major site for the excavation of iron ore, until a mudslide in the early 1980s destroyed much of the settlement. The American ore company quickly departed, leaving what remained of Mano River Kongo to wither and die. Now, six months after a major diamond find just outside town, the population of Mano River Kongo is equal to what it once was, but it is hardly a thriving community. There is a notable lack of children or old men, and very few women of any age. It is a town of male youth, and they squat in the ruins of the school, in tents pitched between old houses, in a half built mosque. For entertainment they play soccer, smoke, and drink tea. All of this takes place in the shadow of the ore bearing mountains, terraced into strange and unstable ziggurat forms during the last mineral rush on the region.

Fields of Vision

For all its risks and scant rewards, the work of mining the border and the landscape it produces are strangely beautiful. The collaborative rhythm of grinding grains with mortar and pestle has long been described as the heart of music and sociality in Africa’s rural life (e.g., Chernoff 1979). No less poetic, however, is the coordinated efforts of loading, washing and sifting sand. And it is work that perhaps better exemplifies the vicissitudes of young men’s lives in West Africa today. Timing matters. A pattern of outward expanding circles begins with the swirling of the gravel and extends to the shape of the screen, then to the motions of the miners’ hands and to the shape of the pit, replicated thousands of times as new claims spread across the forest floor. These circles mirror the social circles that sustain the diamond economy. The labor, however, is young men’s work and it is characterized by young men’s bravado. It takes courage to face the forest, let alone move it out of the way and stack it into piles. Diamond mining is largely unskilled, but some are better at it than others. It is an effort directly tied to the raw physical power of the human form, and the work shapes the body in impossibly exquisite ways—though it does so at great risk and expense.

The centrality of the body to this mode of work, and the work that mining does on the body of the worker, is what animates this project as a visual ethnography. Still photography as ethnography works by “unsettling our accounts of the world” (Poole 2005, 160). Visualizing the relationship between bodies and work can be just such an unsettling for an audience largely alienated from this form of labor. Writing about the documentary photographer Sebastião Salgado’s Workers project, Julian Stallabrass (1997) argued that in those areas of the globe that the neoliberal global economy reserves for immaterial labor, the visual image of working bodies registers as dissonance. Work of that sort today exists almost exclusively beyond the field of vision of those whom it benefits. There is, therefore, a disorienting abruptness to the image of laboring bodies. “The immediate shock,” Stallabrass (1997, 2) writes, “. . . is simply to present contemporary scenes which should long have been banished from the perfectible neoliberal state; to show in a supposedly post-industrial world, scenes of vast pre-industrial labour.”

Alluvial diamond mining in West Africa is not the productive work of postindustrial skilled tradesmen, the only form of manual labor that most residents of the global North regularly encounter. Artisanal mining is purely destructive and extractive. This is labor normally relegated to other points on the globe or conducted deep underground or it is work done by machines. For most viewers, the image of bodies worked and working in this way is startling. There is an excessiveness to the images that terms like work and labor, when rendered as text on the page, simply cannot register. The work, like the miners who do it, has a militant masculinity about it. Text can chart the larger political economy in which the mines and miners are situated (something the images alone cannot adequately do). But only the momentary alienation sparked by the visual image of this mode of work conveys the materiality of West African diamond mining as labor.

The first frame in the series, for example, positions the miner against the pit. Though he has accomplished a great deal already, he is hardly victorious. By this point he has dug his pit, but the process of unearthing gems is far from over and in fact may prove fruitless even when it is complete. He remains surrounded by vastly more forest than he can hope to exploit. But the visual evidence suggests neither resignation nor defeat. Instead the miner has achieved a kind of guarded truce. It is a surprising moment that seems to belong as much to the world of combat as it does to the world of work, with the miner positioned as a soldier surveying recently captured but tenuously held ground. His stance is echoed in the final image of a worker’s shadow cast on the muddy water of the pit. Here, however, the suggestion of both work and war is more active. In the iconic style of socialist realism, his body conflates militancy and manual labor with a simultaneity that is virtually impossible to adequately convey in written ethnography. I have argued elsewhere for understanding the labors of these young men on the battlefield and on the mines as qualitatively identical, but bound by terms like war and work, the text alone inevitably reinscribes a qualitative difference between the two. The image collapses that distinction, and allows it to register as an affront.

Deploying photography’s capacity for discordant images, its power of excessive description (Poole 2005) is not, of course, the only form that the photo essay as visual ethnography can take. W. Eugene Smith’s canonical 1948 Life magazine series “Country Doctor” remains a touchstone for the photo essay as a genre. In it the photo essay acts as a narrative, a series of microdramas with scene setting introductions, suspenseful climax, and visual dénouement. The images in the project I have assembled here are organized less cinematically and more as a collection of figure studies. This is partly because the work of mining itself has no narrative arc (it is endlessly repetitive until—perhaps—the sudden moment of rupture when a major gem is discovered). But it is primarily a function of my desire to limit the scope to the material encounter of the miner’s body with this mode of work and to explore its ready translatability into other forms of violent labor. The argument of the project is synchronic rather than diachronic, and more conductive to a collection of meditations on a theme than to a storytelling progression.

For similar reasons I chose here not to pursue another key direction for visual anthropology, what Anna Grimshaw (2005) has identified as the camera’s unique capacity to record the uncertainties and contingencies of the ethnographic encounter. The camera edits fieldwork encounters in ways that can escape the control of anyone involved in the production of the image, a fact that allows visual work to position the anthropologist more clearly in relation to the ethnographic frame than could be possible in even the most self-reflective text. Yet aesthetically the images I have assembled here owe more to the modernist documentary tradition of photographers such as Lewis Hine, Margaret Bourke-White, or Smith: photographers whose subject position in their images of the work world are hardly neutral or obscured, but photographers who do not make positionality itself the subject of the image. Elsewhere I have critiqued that mode of documentary realism (Hoffman 2007b). So have many others both inside and outside visual anthropology. But here I am less concerned with the photo essay’s capacity for reflexivity than with its capacity for disruption—a modernist impulse inherent in the medium. Many of these images are shot from behind or above. They represent a privileged gaze, to be sure, but they are not images about the gaze per se.

It is the effort to visually render strange the familiar world of work that makes these images ethnographic. Drawing inspiration from Roland Barthes’s seminal Camera Lucida, I set out to open a conversation around a specific set of images that work toward a specific purpose: overcoming the limits of text to visually explore the materiality of a border form of work. This project is not a mediation on the photo essay as such, but an effort to put the photo essay to use as a mode of ethnography. “Nothing to do with a corpus,” as Barthes (1981, 8) put it, “just some bodies.” As the Society for Cultural Anthropology expands the scope for visual ethnography with this new venture, it will be exciting to see the many other borders the photo essay allows us to cross.

Reviewer Comments

Photographic Figure Studies as a Mode of Ethnography?

by Zeynep Devrim Gürsel

Beginning is not only a kind of action; it is also a frame of mind, a kind of work, an attitude, a consciousness.

—Edward Said

This photo essay marks the beginning of a new section of the Cultural Anthropology website. As Said notes elsewhere, beginnings are not just something one does but also something one thinks about. My comments below are an engagement with this inaugural photo essay by Danny Hoffman and reflections on this section and visual anthropology more broadly. Beginnings present a time to think about parameters of enterprises—in this case, the potential uses of photo essays for anthropology. What will the norms of this new section be: Will the photographs always be by anthropologists? What makes a photograph ethnographically interesting? (This might be very different than the journalistic, historic, artistic or pedagogical value of a photograph.) Will the text, images, and layout always be produced by the same person? Given the online presentation, will there be an opportunity to incorporate multimedia? In short, this particular beginning provides an opportunity to collectively think about the photo essay as a mode of ethnography and to reflect on the status of visual ethnographies within our discipline today.

Shaping a Body of Work

In his aptly titled “Corpus: Mining The Border,” Danny Hoffman has given us a rich and provocative trove of text and images that compel us to reflect not merely on the labor behind war and mining near the Sierra Leone border, but also on the photo essay as a mode of ethnography. Hoffman explores many borders here: borders between nations, between text and images, between diverse visual genres and between forms of work. Other viewers/readers will surely add to this list. I’d like to focus on what Hoffman identifies as his conceptual center. In identifying the rationale behind choosing a visual mode for this investigation, he remarks: “The centrality of the body to this mode of work, and the work that the mining does on the body of the worker, is what animates this project as a visual ethnography.” It’s precisely this issue of animation I will address.

The object of analysis in this ethnography is the material bodies of these young men and how they are shaped by their various labors of place-making, whether that place is a mine or a nation. Appropriately, then, these images of young West African male bodies laboring are deliberately not presented in one of visual anthropology’s classic tropes: the step-by-step process or mode of production genre. Hoffman is not trying to teach us the process of how diamonds are mined. His investigation concerns the making of bodies, not diamonds. I take seriously Hoffman’s statement that “this project is not a mediation on the photo essay as such, but an effort to put the photo essay to use as a mode of ethnography.” However, a photo essay is also a body of work and it is to the making of this kind of body that I want to turn briefly in order to better consider it as a mode of ethnography.

A photo essay is a purposefully arranged collection of images often with text, a narrative in which visual elements create themes and dialogues. Hoffman is serving here as photo and text editor as well as anthropologist. Therefore, in order to engage with this photo essay as a mode of ethnography, we need to think not only about the individual images but how they have been arranged. In other words, I believe what makes a photograph or particular set of photographs of interest to anthropologists is not only what is in the image(s), but also how they are put into dialogue with other images, text and/or anthropological questions. Fortunately, Hoffman’s essay contains clues as to how this body of images has been worked on by the anthropologist. By sharing his visual strategies and editorial logic, Hoffman provides the project some reflexivity, even if he claims he is less interested in the photo essay’s capacity for reflexivity.

Working against the grain of narrative expectations inherent to the genre of photo essay, Hoffman states that he does not intend for his photographs to include a narrative arc. His genre is “meditations on a theme,” rather than “storytelling.” He argues that this choice in synchronic visual genre is because “the work of mining itself has no narrative arc” and is “endlessly repetitive.” Indeed, one of the most striking layouts in the essay is the arresting triptych showing three men sifting sand and gravel in a flooded pit. Though they are a series of images, they could also be a single line of laboring bodies, the repetitive nature of their work making it impossible to know whether to read the triptych from right to left or vice versa. What Hoffman’s photography therefore manages to convey is a sheer density of repetitive manual labor: clearly the three frames must have a chronology and, strictly speaking, some form of narrative arc and diachronic structure, but the triptych layout portrays not three individual bodies sifting sand in a particular place and time but functions as a synchronous representation of a workforce.

Hoffman’s creative choice in layout allows him to represent not only laboring individuals but a workforce, a pool of available labor. The interchangeable photographs emphasize the interchangeability of laboring bodies, and visually reproduce a culture where Hoffman tells us young men cycle through the region’s mines, men who “arrive and depart as strangers.” In this triptych, as well as the two images showing bodies working side by side if not necessarily collaboratively, Hoffman is most successful at achieving “an ethnographic portrait of the shape and texture of work.”

Such a project in still photographs is a very ambitious project, indeed. For while it is possible to photograph a human laboring, it is much harder to visualize the more abstract or diffuse political economy or the social circles that sustain diamond mining. Hoffman states that while text “can chart the larger political economy in which the mines and miners are situated,” images alone are inadequate for the task. Instead he substitutes a disciplined study of the “raw physical power of human form.” The resulting images are arranged as “a collection of figure studies.” This borrowing of an artistic genre, figure study, is an opportunity to make explicit the potentially discomforting aesthetic nature of the project: here is an anthropological project asking us “as anthropologists” to look at chiseled black bodies and to take note of the preindustrial work they are doing. Hoffman, in his own words, duplicates what he takes to be the visible work of the diamond mines. It is not merely Hoffman’s professional photographs that render these bodies beautiful; rather, Hoffman informs us, “the work shapes the body in impossibly exquisite ways—though at great risk and expense.” One form of production is substituted for another: chiseled bodies for chiseled stones. Both this work of photography and that of mining aestheticize preindustrial labor. The shapely bodies are visible; the risk and expense are not.

Trained by Catherine Lutz and Jane Collins’s (1993) seminal Reading National Geographic, we need to keep asking for whom and by whom the aestheticization is being done. The absence of even bare-bones captions with information about location and dates might contribute to what Hoffman assumes is a productive “disorienting abruptness” in these images of laboring bodies. Yet the lack of captions also leaves these photographs unmoored, possibly rendering visible a moment where the “temporal displacement” is also of those photographed by the anthropologist. Hoffman’s discussion of startling preindustrial labor that he claims will be unimaginable to most viewers (despite the dense local and international networks his ethnography reveals) suggests that the critique contained in Johannes Fabian’s (1983) Time and the Other remains relevant. While Hoffman’s (2005, 2007a, 2011) other work attests to his long and complex ethnographic engagement with young men in the region, there is little in the photographs or text here that explicitly contextualizes the figures he studies. For the viewer/reader, these human forms remain anonymous human forms. Put more provocatively, how do these photographs differ from Marey or Muybridge’s late-nineteenth century studies of human locomotion? Notably, they are taken not in a studio but very much in the field with the men presumably in their everyday habits of dress (or undress). Nonetheless, the figures in the images remain equally anonymous and out of historical time.

Hoffman is not only a sophisticated and highly skilled photographer, but also a scholar aware of many different photographic traditions (see Hoffman 2007b), a position that requires us to take his editorial choices all the more seriously. He is no doubt very familiar with the oft-repeated criticism of images that render beautiful horror and hardship (such as excruciating physical labor), for he cites the single project at which such criticism has most publicly been leveled: Sebastiao Salgado’s Workers project. Hoffman seems to be grappling in earnest with how to move beyond such debates that are productive as critique, but do not generate alternate ways of imaging. Encouraging either less aesthetic images or solely images of leisure and comfort, or else abandoning visual production altogether would surely be insipid solutions. After all, the photo essay became a popular and highly influential form of visual communication in the mid-twentieth century partly because it provided aesthetic pleasure. The visual scholar Ariella Azoulay (2008) suggests doing away with the distinction between the aesthetic and the political, emphasizing that “no images can exist outside the aesthetic plane.” Freed then from the aesthetic/political binary, we should instead rigorously engage with the political stakes of the aesthetic. Hoffman’s project makes it incumbent upon us not merely to look at what is aesthetically pleasing, but to ask how what is aesthetically compelling came to be so. For whom is this beauty meaningful? For whom are these bodies “exquisite”? Where more apt for such a project than the diamond mines—that troubled site of the crossing of beauty with global politics and economics?

Figure Study as Participant-Observation

Hoffman’s idea of a photo essay as a collection of figure studies is particularly provocative for anthropology. If figure study is “a representation made for study purposes with a live model as the subject matter,” then is it not another mode of ethnography based on participant-observation? I’d like to return here to the issue of what animates a project as a visual ethnography. How is putting the photo essay to use as a mode of ethnography different than illustrating fieldwork or anthropological findings? How might anthropological knowledge animate a photographic project whether the camera is in the hands of an anthropologist or not? Most importantly for our purposes here, what kind of scholarly engagement can a photo essay animate in an audience of anthropologists?

Azoulay’s work is an extremely useful provocation for visual anthropology.1 In her latest book, The Civil Contract of Photography (Azoulay 2008), she is calling for an anthropological engagement with photographs without naming it as such:

The photograph bears the seal of the photographic event, and reconstructing this event requires more than just identifying what is shown in the photograph. One needs to stop looking at the photograph and instead start watching it. The verb “to watch” is usually used for regarding phenomena or moving pictures. It entails dimensions of time and movement that need to be reinscribed in the interpretation of the still photographic image.

Watching photographs, for Azoulay, moves debates about photography beyond the dualistic relationship between the viewer and the photograph (as she claims is the case in the work of Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag) to a space of social relations between the photographer, the viewer and the photographed. Azoulay insists the photographed is not merely a visible presence but an active participant. The universal validity and political ramifications of this larger claim merit a longer debate, one beyond the scope of this review. However, if, as in Hoffman’s work here, we are concerned with photographs based on long-term anthropological fieldwork, taken by the anthropologist himself engaged in participant observation, Azoulay’s claim that the photographed is an active participant would seem to be a given in putting the photo essay to use as a mode of ethnography. In other words, having read Hoffman’s other work, I have no doubt that his research is based on long engagements with his informants whose lives he has charted through significant transitions. But how is this visible in the photo essay before us? Watching Hoffman’s photographs might entail what Deborah Poole (2005) calls a productive form of suspicion. For example, it might lead us to think beyond the usual critique of fixing native subjects as particular racial types instead to ask: how is it that photography simultaneously sediments and fractures the solidity of race as a visual and conceptual fact?

Of course, race is not something that Hoffman addresses explicitly, at least not in the text of this photo essay, and yet it is part of the excessive description that cannot be edited out of his images. Hoffman acknowledges that these photographs represent a privileged gaze but wants them to not be about the (or his) gaze per se. Nonetheless, I am left wondering if the photo essay as a mode of ethnography can ever escape being always also about the gaze. This is not an argument for explicitly self-reflexive work. Rather, it is a call for a reflexivity that does not revolve around a self—Hoffman’s particular encounters in the field in 2010—but instead allows for the viewer/reader to reconstruct the photographic event as a thick description, a still image with all of the social and political context which it implies. Hoffman deliberately turns his attention away from the photo essay’s capacity for reflexivity in favor of its capacity for generative disruption. I am less convinced that these two are separable.

Hoffman writes that he eschews both reflexivity and a narrative arc because of his “desire to limit the scope to the material encounter of the miner’s body with this mode of work and to explore its ready translatability into other forms of violent labor. “ Now, even if it were possible for still photographs to make visible the material encounter of the miner’s body with mining by showing the body in labor or being labored upon by the work itself, “its ready translatability into other forms of violent labor” is knowable to the viewer/reader only because of the anthropologist’s textual reporting on his encounter with the miners. How might such an exploration also have been rendered more visible to the viewer/reader? While I concur wholeheartedly with Hoffman about the potential for the photo essay to function as a mode of ethnography, in the spirit of contributing to a generative conversation about visually animated ethnography, I want to speak to a few areas in this particular photo essay where I believe the visual ethnography might have been pushed even further.

How might the chains of labor in the makeshift camps or social circles that sustain the diamond economy be visualized? Hoffman mentions these things—limiting them, that is, to text—when he might have invited them into a more complicated visual field. The triptych showing men commuting through the forest and playing soccer seems to be a beginning in this direction. What might photographs of the mentioned tents between old houses, or squatters in the ruins of the school or half-built mosque, have added to this essay? Would they detract anything?

Hoffman importantly analyzes the blurred boundaries between labor crews and militia squads and makes a striking argument that there is “a qualitative similarity for many young men between the tasks and rewards of war fighting and the tasks and rewards of mining, campaigning, or tapping rubber.” Presently the visual argument for this lies in Hoffman’s own interpretation of the first frame in the series. What we are to see here, according to Hoffman’s textual voiceover, is a collapse of the distinction between war and work on the part of the young men. Does the image in fact collapse that distinction? War is not visible in this frame but only in the author’s comment. How would we react to a photo essay composed of photographs showing young men engaged in mining, fighting, campaigning, and tapping rubber edited together? I am thinking here of Jean Rouch’s brilliant use of juxtaposition to make visual arguments such as the famous cut between a Hauka spirit possession ceremony and a colonial British military procession in Les maitres fous (1954). How might such juxtapositioning function in a still visual medium?

Alternately, to keep the focus exclusively on the miner’s body, are there bodily marks or gestures that blur boundaries between war and work? Scar stories, for example? Portraits of both war and work are differently told—though possibly not aestheticized—through the physical scars left on the workforce behind these activities. This type of photo essay would almost certainly demand either significantly more ethnographic text for each image or possibly the addition of audio interviews. In fact, Hoffman’s accompanying text begins with “the sounds on the mines” and is a paragraph-long meditation on what can and cannot be aurally registered at the Mayengema mines. Can we think of multimedia as a mode of ethnography? What might be lost or gained if this work were a multimedia piece, rather than a photo essay? Would it animate a different form of engagement?

The Status of the Photo Essay

This review of “Corpus: Mining the Border” is written for the launch of the Photo Essays section of the Cultural Anthropology website. On the one hand, I am encouraged by this initiative and honored to be a part of this inaugural conversation. As a scholar committed to the visual as a field as well as a mode of inquiry and a form of ethnographic representation, I am inspired and heartened that one of the most discipline’s most visible web platforms should feature photo essays. And yet I worry that there is a different, less serious status being granted to projects like this photo essay. What will viewers/readers make of the absence of a blind peer review or editorial process? I’m not concerned merely with academic fairness, but rather, with how the lack of such processes germane to textual publishing contribute to the perception of visual scholarship.

We need to think critically not only about photography, but about how images are brokered. Image brokers are the people who act as intermediaries for images by moving them or restricting their movement, thereby enabling or policing their availability to new audiences (Gürsel 2012). By inaugurating this photo essay form, the Society for Cultural Anthropology (SCA) is serving as an image broker. What are the terms, then, of this brokering? Does this new online photo essay format promote visual ethnography or marginalize it further? For example, Cultural Anthropology published Hoffman’s excellent article “Violence, Just in Time: War and Work in Contemporary West Africa” in the journal just a few months before this online photo essay. The article contained no images. The photographs that comprise “Corpus: Mining the Border” are clearly informed by the same ethnographic research and theoretical concerns, yet they are being published separately and evidently with a different set of academic—or is it aesthetic?—expectations. I invite us all to debate the merits and costs of this separation of images in the SCA’s publishing program and believe this is a very timely discussion for the discipline at large.2

A twenty-fifth anniversary edition of Writing Culture has recently been published with a foreword (by the former editor of Cultural Anthropology) highlighting how it changed the face of ethnography. Interpretive anthropology was animated by a desire to “contribute to an increasing visibility of the creative (and in a broad sense poetic) processes by which ‘cultural’ objects are invented and treated as meaningful.” Perhaps we ought to treat such an anniversary as a new beginning as well, not to return to the by now tired debates in which everyone has long ago staked their position, but to seize the opportunity to rigorously interrogate modes of ethnography for a new generation. Having thoroughly debated self-reflexivity, perhaps it is time for media/modal reflexivity.

It is time to begin evaluating anthropological scholarship not only on its content but also on its chosen medium.3 I certainly don’t mean that all anthropology articles should now have superficial visuals or multimedia attached to them. (The colonization of classroom lectures by obligatory PowerPoint is proof enough that mandatory visuals are by no means necessarily illuminating.) Rather, at a moment when many anthropologists are engaging with different forms of media, it is now feasible and meaningful to make the choice of medium one aspect of evaluating anthropological work. There has been a lot of work done to legitimate visual work in anthropology, as in the “Guidelines for the Evaluation of Ethnographic Visual Media” created by the Society for Visual Anthropology. But I am asking if we have come to a moment where we ask not whether a particular visual ethnography is adequate or valuable or ought to “count,” but rather begin with the question: what is the mode of this ethnographic inquiry, and how can we engage with it in an analytically rigorous way? Different modes and mediums require that makers, brokers, and the reader/viewers develop new forms of rigorous analytic engagement. What do we still need to learn as a discipline to debate costs and benefits of using different media? Will we ever ask: was text the best mode for this ethnography? I believe that articulating answers to such a question will help develop analytic rigor across media. I hope that many of you will join this conversation and contribute to a discussion not only on putting the photo essay to use as a mode of ethnography, but also on the theoretical claims and ethnographic material that Hoffman has shared.

Notes

1. Azoulay’s work is similar, in this sense, to the work of artist and critic Allan Sekula and art historian John Tagg, and indeed builds on the work of both.

2. It is true that films are corralled off at the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association, rather than integrated into panels. However, this is a new beginning and beginnings are a moment to reflect on forms.

3. My interest is in contributing to a debate about how visual scholarship can most effectively be part of a diverse range of anthropological conversations. I am inspired by Ethnographic Terminalia, as “a project aimed at fostering art-based practices among anthropologists and other cultural investigators or critics” that is analytically sharp and highly media-reflexive. Its website has been central to its efforts to gain greater recognition for the work of visual anthropology, serves as both a tool for promotion and an archive for legitimation. Collectively, all those involved in Ethnographic Terminalia have creatively celebrated boundaries and borders without exalting them and have launched a generative conversation about the terms of ethnography. Yet that is a conversation happening on a different website, one that might not be sought out by those not already engaged in some form of visual anthropology. The beginning, of which this review is a part, requires the thinking of the stakes and productive possibilities of having similar formal conversations on the Cultural Anthropology website.

Not Just Bodies

by Alan Klima

Danny Hoffman's broad strokes and starkly juxtaposed, figural swathes of color and shade are conscious and deliberate challenges for a conversation on possible meanings of the photo essay for anthropology today.

I quite like the aesthetic eye of the images, understand the author's attempt to situate that style for the reader, and understand the author's attempt to explain why the style is not otherwise. Although sometimes reading like a strategic fending off of template criticisms readers might have come across in the past and tucked in their back pocket should they ever have the occasion to come across an image again, the ruminations on visual anthropology do accomplish, at the very least, this highlighting of Hoffman's strong sense of aesthetic purpose, one I would further call attention to in the abstract and formalist elements of his image composition. Although still resembling the aesthetic of photojournalism, to me these photos tip quite a bit toward the abstract in their broad patches of color and large shapes, and less toward the prosaic sensationalism that photo-journalism seeks.

I don't find the photographs the least bit shocking, except in the sense of "wow, soil can look like that!" And this is so even as I am surrounded by the equally brilliant, though red-tinted, soil in Thailand. Neither did I see the content or form of what is in the photographs as “qualitatively identical” to warfare nor that the image collapses the distinction between work and war (while text can only distinguish them), as the author asserts. In fact, contrary to the author's view, I would need it to be explained, in text, exactly why they are the same as war; otherwise, I won’t see it. And still, I am not sure that I would. As image only, I have to say I find them qualitatively identical to rice farming in rural Thailand, and it would take a whole lot of words to override my eyes.

The adamant style and stance of the images, themselves, however do accomplish Hoffman’s stated goal of providing a jarring impetus for new meaning of the reproducible image mode to anthropology. How he characterizes this intervention is, by contrast, worth questioning a bit.

Hoffman’s presumption seems to rest on an idea that the photographs are communicating brutal labor, and that this would be shocking to the viewer: “For most viewers, the image of bodies worked and working in this way is startling.” Although I appreciate the photography very much and do find something jarring about it, it is not due to the seeing of the harsh work depicted in them. What I see in any given photograph—as image, quite apart from what I am told is there—is people digging with shovels, sifting about in the water, etc., something I see all the time, and I imagine this is just as familiar to most viewers. It is even more curious to be told that this is “not the productive work of postindustrial skilled tradesmen, the only form of manual labor that most residents of the global North regularly encounter.” Never mind that this is an essay on the Cultural Anthropology website, whose visitors are probably not confined to continual residence in the global North—my university home is in Northern California, where manual work in the hot sun abounds and can’t not be seen. How many other places in the global North must there be like California? I grew up the son of an academic and an artist all the way on the other coast, and had to spend long periods of my youth, like many around me, in manual labor, bending sheets of metal to the same forty-five-degree angle for hours on end, or stacking mountainous piles of lumber and damaging my body. Not that this helps me to assimilate or understand the reality of diamond mining one bit (well, a bit). It’s that, without being told the story around the acts depicted in the photos, there is little to distinguish them from all the other forms of unskilled manual labor that are very close and common in the North, if you only look around a bit, and everywhere else for that matter. Destructive or productive, there is no way to tell from the image. People stand knee-deep in water and bend down in rice farming, and have for thousands of years. Alluvial diamond mining itself may be shocking, but these are not the kind of sensation-mining photos that can deliver it one swoop. The stereotypical photojournalist's goal of bringing shocking news, or the stereotypical ethnographer's goal of bringing exotic otherness, is simply not accomplished in these simple scenes of what are, visually alone, ubiquitous acts.

I do not deny, however, Hoffman’s assertion that there is something jarring about this photography, nor does my intellect permit me to deny that there may be something here in this diamond mining that is, in truth, insanely harsher than anything I normally see among migrant workers on the hot, smoggy plains of California, or—certainly—have experienced myself. But we are supposed to understand that it is only the image that can communicate this material level of labor, a materiality that is ethnographically exotic to the North and thus defines the purpose of this photo essay: “overcoming the limits of text to visually explore the materiality of a border form of work,” where the “bodies of the miners are stripped to their essence by hard repetitive work and the hard repetitive landscape,” and therefore there is “an excessiveness to the images that terms like work and labor, when rendered as text on the page, simply cannot register.”

Yet what is jarring is not the unfamiliarity of unskilled manual labor, but the fact that it is actually not shocking at all to view these photographs, and yet somehow, it should be. This it should be is integrated into the composition and attraction of these photographs: the aesthetic shapes of the scenes, and especially that of soil and the body, strike the eye with form, and yet are not fully grasped, reckoned, realized as content, as real-life experience, at least not as image. The lack of shock, moreover, is made all the more obvious by its pairing with abstract forms of aesthetic beauty. It is the beauty of the photographs, and simultaneous richness of presence to the soil and body, creating a jarring disjuncture that calls attention simultaneously to the struggle depicted in figure and ground, between the figures and the ground, and a struggle for the viewer to reckon with what powers and forces—not only matter, but energy too—are at work here.

This leaves the question of the experience of this labor open, because, in my view, there is also present in the images a human power that is truly awesome and beautiful and unfathomable and yet somehow carried in the photography.

And, which is quite unlike the stripped bare materiality of manual labor Hoffman asserts in his textually expressed views.

True, in repetitive, manual labor there are aches. There is exhaustion, and damage to the functioning of the body, but there are also all the thoughts and reactions to those sensations in the body, which in turn interact with them, amplify and alter them, a process that if watched carefully reveals that it is impossible to tell where one starts and where the other ends. And in any case, consciousness is required for there to be any feeling whatsoever, unlike a corpse, zombie, or patient under general anesthesia, where materiality exists but pain and suffering does not.

The experience of manual labor is not a simple material fact and no worker is ever ground down to a pure material level. In fact, labor transpires in a mental medium, including all kinds of thoughts, reactions, and, indeed, stories. These miners are working within a story, even if it is not obvious. Even if there is no narrative arc to mining itself, there is for the miners.

And story, in manual labor, is perhaps the most painful aspect of it all. Whatever story is—and it is various and it can change—it sits over your shoulder, multiplying itself into more stories, into resistance to what is happening, longing for another kind of life, and all kinds of desperation. One procedure that is absolutely fundamental to performing brutal manual labor is shutting out this story (whatever it is), watching for its insistent return, and then banishing and re-banishing it, again and again. Some might be so good at it that they no longer realize what they are doing. Most people I have spoken to, however, never completely banish the stories, but they can shut them out for a time. If you can’t do that, you can’t work for long, because it will seize upon the so-called material sensations that are themselves already mixed in a soup of mental reactivities and tip the whole unbalance in a more calamitous way: more pain, probably injuries and sickness, and certainly no will to go on.

And so both the simple idea of material labor, and the idea Hoffman offers of story and narrative that are somehow not present in the arc of simple, repetitive digging in the soil (narrative as might be defined by pretending twentieth-century literature never happened) close off too neatly the idea of labor in the material world in a way that has been too common for too long. It also fits neatly into the idea that the material world is the province of the image and photography. Each to its own place.

In the essay, the proper place for text is to describe the context, set the scene, explain the political and economic setting. To me, a most unfortunate career for writing.

Then, in comes the image: to do what text cannot, and the photo essay becomes an essential antidote to the written word.

Actually, I share with Hoffman a hope for the photo essay—and any other manifestations of anthropology-through-image that may arise—but if that hope is conjured in the figure of nontext, against text, with each given its appropriate purview, then old assumptions are restrengthened, the same measures of inadequacy apportioned out, which marginalize the visual on the one hand and flatten the textual on the other. In fact, no worse outcome for the revival of visual anthropology could be possible than reinforcing the atrophied and lifeless conception of text that, if not consciously held in the ethnographic mind, is nevertheless demonstrated to be dominant in a significant portion of anthropological prose.

Photography has more intrinsic value than as antidote to the inadequacies of prose. It can make a better case for itself than that in anthropology. And, after all, most of the limits of text Hoffman speaks of are, in anthropology, actually limits either in the writers themselves or in the system by which prose is selected and published, not of text itself.

Instead, photography should rise to the occasion and assert itself, make no excuses and no apologies for its existence. And to do that it might be helpful at the same time to recognize the immense power of writing, and accomplishments of writing. In fact, it is no easy thing at all to match the power of writing in addressing the experience of brutal labor (and such labor is never simply material, not for the people who do it). For Hoffman, through his photography, to have matched writing in this task is no small accomplishment, and it was not an accomplishment that was made simply by switching media.

Hoffman’s images have risen to this occasion, and despite what he might say, open up for us our idea of labor and materiality rather than pinch them down into familiar tread.

And so, to return again to the photographs: rather than feeling shocked at the harsh labor I was visually exposed to—actually a common photojournalist’s goal, I can assure you, having asked at least a few—I found myself kicking myself to try and force myself to feel the extremities of the experience here, but the wall of Hoffman's photographs was something I could not push myself through.

Of course, I am not so naive as to throw up my hands and declare photography inadequate.

Instead, I became all the more fascinated by the photographs and appreciative of the work Hoffman has done. And this continuously escaping affect, if you will, is no fault of the photography. In fact it is precisely this tension which is so subtly involving about the photos: that every piece of information was telling me that there was something extreme, special, alter about the experience of the bodies in these pictures, and yet I am unable to pick it up and instead see form. This discomfort itself is part of what is of value in the photographs for me, because nevertheless the constant beckoning of sweat and soil is so intensely present and would not let me stop trying.

A too-neat conception of materiality considerably closes these and other disjunctures, closing off what should be an open question on the nature of labor, in a way Hoffman’s photographs themselves do not.

This particular kind of openness is not as present in the early work of the great photographer Sebastião Salgado, for instance, where narrative within the frame is thick and obvious—the gold mining scenes being the obvious comparison. How different, and how easy and comfortable in this sense, are Salgado's early and mid-career photos, where one gets an overload of meaning in a baroque sense of the fantastic and strange, even Bosch-like hell evoked at times, and magically so: surprisingly, through figures that can be only ever real, unlike Bosch who did it through imagined grotesqueries (or at least those who have not actually seen hell might believe). In Salgado, the radical alterity of brutal labor is spelled out for us, as it were, and its shocking reality is indeed conveyed through the very surreality of the compositions.

If photojournalism has a most highest and unattainable level of heaven, it is Sebastião Salgado.

Something quite different is happening in these photographs. Context and strange awesome scenes are not attended to, and something much quieter remains, held in the hand of abstract form.

And that both is—and isn’t—the materiality that Hoffman is right to say is an important evocation in the images.

Precisely: this pointing to the earth element of body and soil, the material aspect of it, and yet, with a tension—and this is what is so jarring and challenging about the photographs—because of course nothing is less suggestive of the earth element than the abstract shape and form and the aesthetic balances of light, dark, color and line of these photos. Whereas Salgado elided this tension through the immense storytelling functions of his photos, letting the baroque extravagance of his realism and the overflow of meaning almost deceptively distract from what can only be said to be an equal emphasis on figural form, Hoffman leaves us no out: either remain transfixed by abstraction, which he well knows is impossible for any caring individual to do, or jump ship, ponder the unattainable connection to the experience of this kind of work, this life situation, this labor.

As in the halting, liminal beginning and first picture of the series: not yet shocked by the wash of golden soil that is about to flail itself against the retina in the photos to come, the eye can at first pause, along with or behind a pause in the contemplative pose of the first figure, who is perhaps hesitant to begin work, who is perhaps surveying work to be done, or perhaps is marinating in that moment after hard work, a moment that lingers on longer than you intended, and it’s so difficult to start up again.

Then the second photo in this mostly warmly lit series: a distinctively cool color scheme, yet hitting off the first hint of what is really to come in the rest: broad swathes and patches of form and color in harsh juxtaposition. In this photo, one also picks up the first hint of struggle, perhaps with exhaustion or with the limits of the body, perhaps with soil. In this figure of simultaneous work and rest, and like in most conventional narrative beginnings, it looks as though the strength and power of the protagonist may be defeated.

But this is all called into question with the frantic energy of the third photo, where—in an oddly angled shot and oddly angled act of work—plants spread their knives, competing against each other to mine the sun, and the body grows fingers in a frantic race to contact, one is told, diamonds (which we never see). In this strife, the plants seek contact with a sun that gives without receiving in a project that can only ever end in their death, while the fingers that dig, sort, sift for limited, unseen objects—their project does not die. This search itself is as immortal as the desires and systems driving it are limitless, can never end, and will outlive these hands for sure.

In the fourth view, a series framed and colored in a way so reminiscent of the bathing scenes in Trinh’s Reassemblage, there is juxtaposition of time-lapsed shots reminiscent of her breakup of cinematic form, and yet in its adherence to temporal series so unlike it is as well. Here the classic ethnographic narrative of this is how it is done: A, B, C is adhered to, in thumbnail form appearing to be a strange panoramic shot but in close up actually an interested study in a complex action simply presented.

And for that, so disjunctive with the high-stakes flurry of the preceding image.

By the fifth image there can be no doubt where the essay’s aesthetic allegiances lie. Here Grecian, statuesque attraction to the male body combines with the strongest attention to large swathes of aesthetic form, in the most abstract and yet most telling photo of the series. In the midst of all these large forms, the eye is drawn soon into something, tiny, intricate, and exuding from the surface, the sweat: a cool reminder of how inscrutable—as photograph—the experience of this labor is. No heat whatsoever is communicated in the formal line and shape, and yet, there it is: dancing on the surface, the indisputable evidence, all the clearer for not having been felt in the viewer, the indisputable traces scintillating in the power of labor meeting heat, and the struggle that began in Image 2 now looks like it might be swinging the other way: a power of unknown limits is at work here, under the skin. Which is more impressive? Is it the fact that this miraculous human power exists at all, and can be unleashed at will, as seen here, or is it the fact, more known through the political and economic context, that this miracle can seem to be chained, that there is—in what is nonvisible to this particular photo essay—a power-harnessing-power, native to the social structures that render seemingly necessary this hard work in the sun, a power compacted by many confluences of fear of death with greed for shiny objects, with the numerical excitement for profit and wealth, with the ache to control land, people, other bodies. But I digress, as this photo does not call up that daunting awe. It is regnant with power, only power.

And so, in Image 6, it is no surprise that—returning to the prosaic world—even a sea of golden dirt cannot defeat these slight figures, who, in a more staid, less sensational version of photojournalism, are demonstrating the action that defines them within their life-in-this-text.

In the following view, a somewhat disjunctive series, in discontinuous semiosis:

The journey to the interior.

Then, a human will exacted upon nature, tearing like monster claws into the soil.

But . . .

not deep,

in the larger scale of things, and

Finally, the soaring life of—again—this power that cannot be contained within the frame of labor, not within the frame of exploitation: a power of amazing reach, unfurling itself in the failing light of day on a great peal of energy riding beyond pain, beyond all creaky calls of the body that is dying in every moment.

Dying, but it does not matter.

Not matter.

And now, in Image 8, returning again to the strange orange glow of the soil, there is something of a blow delivered here, but almost an afterthought. One foot barely hovering off the ground, still hints of soaring, but not high, not really flying at all, but propped on the weight of a force delivered into the soil, which, in this framing, no longer dwarfs and surrounds the man but appears to have already yielded to him.

Image 9: back to banality. It is work after all. Moments repeating themselves. Circles.

And finally, shadow upon swirling water, another figure of domination, posed in a mastery of the elements, and yet, as the final photo, suggesting also something of a ghost, something of the acorporeal, just form of light, just shadow: which, after all, is all there really is here anywhere in the photos. That this is photography, light and shadow, is something we are not encouraged to forget for long in this photo essay, if ever. And yet . . .

And yet still the seeping muck of water and mud, the fine as well as chunky granulations of the sun-baked soil all around, suggest so much of the elemental, the material as well, so resonant and goopy and almost palpable. Here, the soil is given power and presence, and the human: it remains a question. Power, and yet of what kind, what being?

Reader/Viewer Comments

by Eleana Kim

This inaugural photo essay and the accompanying reviews are wonderfully rich and provocative. I had a number of initial reactions to the essay that were eloquently articulated by the reviewers, particularly around the gaze, the notion of labor as startling and how to view bodies presented in ways that eschew narrative arc and foreground formal simplicity. What I'm most interested in is how the images, in an odd way, through the narrow focus on the sites of physical labor and laboring bodies, reproduces the alienated labor of capital. Perhaps this is the point, in a way, and the convergence of politics and aesthetics becomes clear through this interpretation. Yet, looking at these laboring bodies, I wondered how one could disrupt the smooth aesthetics of the images to convey a sense of the ethnographer as a laboring body (as opposed to merely an observing presence), especially through the medium of still photography (for a fascinating project on labor through a distributed video collective, see Harun Farocki’s new project: Labour in a Single Shot) and how the (nonalienated) labor of the ethnographer/imagemaker is produced alongside the (alienated) labor of the photographic subjects. The use of photography in the production of generic bodies or anatomies has a very long history, as Zeynep Gürsel reminds us. In referring to Les Maîtres Fous, she also reminded me of the ways in which the Hauka possession ritual that is the putative subject of Rouch’s film is the unconscious subtext for the other narrative, of migrant labor. This is a form of reflexivity (however overdetermined Rouch’s resistant interpretation may seem to us now) that returns us to the political economic contexts in which these migrants labor and struggle for social power.

by Jenny Tang

Danny Hoffman’s photo essay, “Corpus: Mining the Border,” presents ten vividly colored photographs of young black male bodies juxtaposed with text describing the paradigms and structures that circumscribe their experiences living and working in border mining towns between Sierra Leone and Liberia. The contents and format of this body of work are immediately fraught with tension. On the one hand, the photographs, beautiful abstractions that, to me, recall the work of Robert Mapplethorpe much more than the modernist documentary photographers that Hoffman cites as his predecessors, represent these bodies as aesthetic entities. On the other hand, the text that accompanies these photographs recalls the mainstream photojournalism that one might find on the websites of the Times and other major newspapers.

Hoffman insists that he is “less concerned with the photo-essay’s capacity for reflexivity than with its capacity for disruption” by “unsettling an audience largely alienated from this form of labor.” While an act of disruption may unsettle and even redefine borders (and serve to render the familiar strange), it may also render visible previously unnoticed seams and lines of distinction. In doing so, does not the act of disruption itself help constitute the border that it seeks so earnestly to unmoor? Thus, what these photographs seem to disrupt is not so much the border between the privileged viewer’s life and the laborious lives of these men, but the border between word and image, between ethnographic labor and aesthetic labor. This seems to me to be the fundamental aporia that Hoffman’s photo essay struggles with, and a paradox that is made explicit on a formal level.

To begin with, Hoffman asserts that images have a power of excessive description which text cannot and does not have access to: text can chart the larger political economy in which the mines and miners are situated (something the images alone cannot adequately do). But only the momentary alienation sparked by the visual image of this mode of work conveys the materiality of Western African diamond mining as labor.

Yet Hoffman’s text does not chart the larger political economy of miners, besides giving brief descriptions of Mayengema and the fighting factions on both sides of the border. Instead, the text describes and insists on the materiality and sensuality of abstract terms like work and labor:

The sounds on the mines around Mayengema are scratchy, percussive sounds.

Work on the mines is sisyphean. Diamonds are carried across this landscape by century after century of moving water and shifting earth. One accesses them by panning creeks and river floors or by scrapping away the topsoil.

The work is always hot and always hard.

And although Hoffman self-consciously refrains from composing a photo essay cinematically, with the arc of a narrative, the text itself seems to supplement or compensate for the lack of a visual narrative with a textual one. Hoffman describes the process of mining and even narrates the possible scandal of a crew slipping away in the middle of the night because they had calculated and judged the value of the discovered stone to be greater than the risk of flight. The place of narrative is made most explicit when, in the eighth frame of his photo essay, Hoffman harks back to the first image in the series. For seven frames, we have had no explanation or analysis of this opening image, and to have one now is startling and almost confrontational. This momentary asynchrony makes apparent to the viewer/reader that, while the text and images do not form a narrative in the sense that the images do not illustrate the text, we have still been enmeshed all along in a different sort of narrative.

Like the concentric circles that Hoffman describes, in which the circles of gravel and pits “mirror the social circles that sustain the diamond economy,” we are meant to extrapolate from Hoffman’s abstractions and generalizations some sense of the specificity of these men’s lives. The mood and the tone of Hoffman’s writing seems at times to verge on magical realism, and fittingly so, for the genre of magical realism constructs a world in which the transcendental and the historical live side by side. Hoffman’s doomed American ore company, for example, echoes the doomed banana company of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude:

These towns are swollen with men. For Mano River Kongo it is not the first time. This was once a major site for the excavation of iron ore, until a mudslide in the early 1980s destroyed much of the settlement. The American ore company quickly departed, leaving what remained of Mano River Kongo to wither and die.

What this amounts to, as Zeynep Gürsel astutely notes, is that these men remain “anonymous and out of historical time.”

Meanwhile, the images seem not so much to signify the excess materiality of labor that cannot be captured through words, but the aesthetic labor of Hoffman himself. His camera seems interested, not only in making sense of these bodies shaped by and exchanged in labor, but the sensuality of the bodies themselves. The erotic undertone that runs throughout these images seem part and parcel of a longstanding discourse that renders black male bodies just that: bodies, without faces and without names; bodies whose excessive energies, when harnessed, may produce, refine, and even make profit, but unhindered, threatens an excess of sexual drive. This is a particularly American discourse stemming from our history of slavery, yet it is one which Hoffman’s images cannot escape. Hoffman writes that it is the “effort to visually render strange the familiar world of work that makes these images ethnographic,” but perhaps what is rendered strange is not the world of work but our conceptions of race and blackness, displaced onto an alien context.

Ultimately, Hoffman’s photo essay makes clear that an ethnographic project is always already an aesthetic one. Perhaps this is why Hoffman feels a kinship with Lewis Hine and other modernist documentary photographers, for they were working at a time when the place of photography as aesthetic object (as embodied by the Pictorialists and Photo-Secessionists) and as social document was being debated, and these oppositional positions articulated. For Hoffman, to disrupt the border between these two is to question the stakes on which the distinctions were made in the first place.

References

Azoulay, Ariella. 2008. The Civil Contract of Photography. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang. Originally published in 1980.

Chernoff, John. 1979. African Rhythms and African Sensibilities: Aesthetics and Social Action in African Musical Idioms. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

Grimshaw, Anna. 2005. “Eyeing the Field: New Horizons for Visual Anthropology.” In Visualizing Anthropology: Experimenting with Image-Based Ethnography, edited by Anna Grimshaw and Amanda Ravetz, 17–30. Portland, Ore.: Intellect.

Gürsel, Zeynep Devrim. 2012. “The Politics of Wire Service Photography: Infrastructures of Representations in a Digital Newsroom.” American Ethnologist 39, no. 1: 71–89.

Hoffman, Danny. 2005. “The Brookfields Hotel (Freetown, Sierra Leone).” Public Culture 17, no. 1: 55–74.

_____. 2007a. “The City as Barracks: Freetown, Monrovia, and the Organization of Violence in Postcolonial African Cities.” Cultural Anthropology 22, no. 3: 400–428.

_____. 2007b. “The Disappeared: Images of the Environment at Freetown’s Urban Margins.” Visual Studies 22, no. 2: 104–119.

_____. 2011a. “Violence, Just in Time: War and Work in West Africa.” Cultural Anthropology 26, no. 1: 34–57.

_____. 2011b. The War Machines: Young Men and Violence in Sierra Leone and Liberia. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Lutz, Catherine A., and Jane L. Collins. 1993. Reading National Geographic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Poole, Deborah. 2005. “An Excess of Description: Ethnography, Race, and Visual Technologies.” Annual Review of Anthropology 34: 159–79.

Stallabrass, Julian. 1997. “Sebastião Salgado and Fine Art Photojournalism.” New Left Review, no. 223.