I called Yesenia on a Tuesday afternoon, but she didn’t answer. My number wouldn’t be familiar to her, as I wasn’t her son’s teacher, nor was I employed by the school district. I volunteered to translate a message for my friend, a teacher, who was concerned that Yesenia’s son hadn’t signed onto Google Classroom by day two of the Covid-19 homeschool order. The Spanish translators for the district were overwhelmed with requests and the teacher was worried that her student would fall behind. I texted Yesenia in Spanish and she called me back. When I hung up the phone, I felt like I had both violated her privacy and overwhelmed her. I also considered the responsibility we both faced as mothers of young children. What would the California school district require us to accomplish in the next uncertain months, and what would be possible for parents who were unable to shelter in place? Yesenia worked long hours at the local gas station during the day, she said, so she wasn’t able to be home for morning Zoom meetings with her son’s teacher.

Yesenia is one of thousands of women in California who have gone unnoticed in the public rhetoric surrounding the national stay-at-home order. In a recent speech, California Governor Gavin Newsom ignored the socioeconomic realities of women like Yesenia working in suddenly dangerous conditions, or as the single head of household, confronted with the shift to completely privatized labor of educating their children without adequate time or resources. These people, as they had been before the viral outbreak, were invisible to the state: “I just want to go deeply to express an appreciation to all the moms . . . I know how stressful this is,” Newsom remarked.

The version of mothering described by the state was addressed to those who were able to both work from home and perform homeschooling labor simultaneously. Newsom remarked that women, specifically mothers, were disproportionately placed at the forefront of the mission, but he did not address the fact that closing schools only magnified the centralization of the nuclear family in an already highly privatized neoliberal state, further removing community support from mothers who had a suddenly precarious relation to resources.

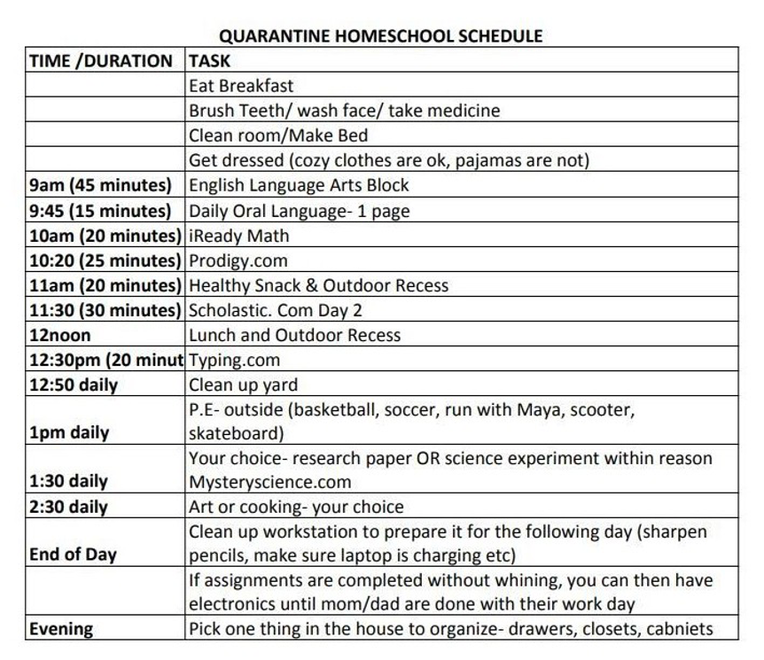

I have been conducting autoethnographic research on intensive mothering within these nuclear family households in Orange County, California, since 2017. According to sociologist Sharon Hays (1998, 3), intensive mothering assumes that mothers should be primarily responsible for “child-centered, expert-guided, emotionally absorbing, labor intensive, and financially expensive system of childrearing.” I was interested in this ideology’s pervasiveness in the public school system and my social media feed, but during the pandemic I became increasingly preoccupied with the stratified social organization of parenting that structured visibility and access to resources necessary for successful parenting. Many mothers in my community who were economically privileged had made the decision not to work outside the home, and they posted images of their quotidian routines on social media. For these wealthy few, California’s shelter-in-place order had shifted those images to detailed homeschooling schedules (see fig. 1) and photos of children participating in live Zoom meetings with their classes. It was the only medium for performing intensive motherhood in a recently quarantined, socially distanced community.

Newsom’s remarks translated into visibility for these mothers exclusively.

The situation for many families in California, on the other hand, is one of economic precarity that intersects with racial and linguistic power structures to marginalize children in the public school system en masse. Almost 20 percent of all children in the state of California live at or below poverty level and over 44 percent of California households primarily speak a language other than English. The members of what I call an invisible population in my 2005 research on “newcomer” immigrant children who live in multi-family households in upper class communities have historically been called “underserved,” but more recent, accurate descriptions of these groups describe them as “under-resourced” (Donaldson 2005). Only 55 percent of low income households in California had access to broadband internet before the Covid-19 outbreak, and media reports that free wifi would be provided to those who needed it would undoubtedly take several weeks, time, and costly efforts to arrange. And, amid anti-immigrant policies that waffled on such issues as bilingual education in California classrooms, many teachers were ill-equipped to communicate with students’ caregivers without the proper infrastructure in place to meet the multilingual, multifaceted needs of the children they were suddenly required to educate from a distance.

Shellee Colen (1995, 78), in her examination of immigrant experiences and meanings of motherhood, provides a synthetic overview of the “transnational experience of stratified reproduction,” which is unequally “valued and rewarded” for those whose social and historical pasts align with such structures as America’s lingua franca. Like 45 percent of California’s population that is low income, these immigrants fall outside of the state’s purview, challenging the social control system that benefits from English-speaking, socially valuable women who do not require additional state resources to be productive. Mothers who Newsom acknowledged are simultaneously “manag[ing] the household” and “making sure they’re taking care of their own . . . childcare needs” without state assistance are economically adaptive, while those who do not uphold this stratified system are a burden on the apparatus. The invisibility of California’s low-income quantitative majority highlights the asymmetrical power systems that keep them hidden while highlighting those who make up the intensive mothering front lines.

Parents like Yesenia who struggle to keep up with the late-capitalist mandate to perform an unrealistic amount of work at home will remain invisible in the months to come. The governor’s speech made this clear. Newsom “empathized” with mothers, he said, but the state mandate for homeschooling to continue reflected a contradictory political meaning. Politics of recognition refuse to support mothers in precarious conditions like Yesenia’s, and California’s homeschooling program continues unabated. The reality is that when schools reopen, some children will return with more of an academic advantage than they had before the Covid-19 outbreak and others will be further behind than when it began.

References

Colen, Shellee. 1995. “‘Like a Mother to Them’: Stratified Reproduction and West Indian Childcare Workers and Employers in New York.” In Conceiving the New World Order: The Global Politics of Reproduction, edited by Faye D. Ginsburg and Rayna Rapp, 78–102. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Donaldson, Lindsay. 2005. “Jaula de Oro: The Experiences of Latinx High School Students in a North American High School.” Unpublished manuscript.

Hays, Sharon. 1998. The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. New Haven: Yale University Press.