This post builds on the research article “Dear Dr. Freud,” which was published in the May 2014 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editorial Footnotes

Cultural Anthropology has published a variety of articles on death and mourning, including Jean Langford's "Gifts Intercepted: Biopolitics and Spirit Debt" (2009); Andrew Orta's “Burying the Past: Locality, Lived History, and Death in an Aymara Ritual of Remembrance” (2002); Robert Desjarlais's “Echoes of a Yolmo Buddhist's Life, in Death” (2000); and Cecilia McCallum's “Consuming Pity: The Production of Death among the Cashinahua” (1999).

Cultural Anthropology has published a number of articles on precariousness, including Noelle Molé’s “Existential Damages: The Injury of Precarity Goes to Court” (2013); Hayder Al-Mohammad’s “A Kidnapping in Basra: the Struggles and Precariousness of Life in Post-invasion Iraq” (2012); and Kathleen Stewart’s “Precarity’s Forms” (2012).

About the Author

Charles Briggs is a professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley. He received his PhD from the University of Chicago in 1981. His research and teaching center on the development of critical perspectives that cross national, disciplinary, epistemological, and the academic/activist divides. His research focus is in the United States and Latin America where he combines linguistic and medical anthropology with social/cultural anthropology and folkloristics. Briggs has explored many topics, but his primary object of inquiry is how precarious poetics and social constructions of language, communication, and media are structured by everyday life in zones of racialization, power, danger, and often death. For more on Professor Briggs’s work and to view a list of his selected publications visit his faculty page.

Photo Essay

Text and images by Charles Briggs

Somehow, placing myself within a conventional academic voice didn’t work for this project. I tried several times over a number of years, and I just couldn’t create the sort of space I needed to write about an unforeseen, consequential, and rather painful collaboration in confronting a mysterious disease. Once I slipped into the more open and intimate space that emerge in writing a letter to Dr. Freud, I could explore in a more satisfying way how I found myself simultaneously interpellated by parents who had lost children and Sigmund Freud’s work on mourning.

Accordingly, the last thing I want to do here is to create a conventional academic surround that would enclose either the letter or the epidemic. The place that I was assigned in this work of mourning accorded great priority to the visual. Parents and community leaders asked me to create photographs and video footage, both as part of their efforts to confront the social deaths of the individuals who died and to make their demands mobile. I was able to draw on a nascent career as a documentary photographer that had been on hold for decades. As painful as it was to photograph crying parents who had just described their children’s deaths, my cameras seemed to be magically taken over by the power of the parents’ witnessing.

An excellent photographer, Miguel Gandert (Director of the Interdisciplinary Film and Digital Media Program, University of New Mexico), curated an exhibition of these photographs. It is entitled “Tell Me Why My Children Died!” This is the demand we so often heard when visiting affected communities. The exhibition has toured Brazil, and it was displayed at the Lichtenberg-Kolleg of the University of Göttingen in Germany in July of 2013. I provide a small selection here.

For the Göttingen exhibition, Antoinette Saxer kindly took video materials that I assembled and edited a short film; she granted us permission to include it here. Kalim Smith also assisted with the initial editing. I provide here two short videos that will afford readers/viewers a different type of encounter with two crucial moments in which I dwell in the text: what Clara Mantini-Briggs, Norbelys Gómez, Tirso Gómez, and I saw when we arrived at the Macotera-Pizarro house in Muaina and the portion of Florencia Macotera’s account of her son, Dalvi’s death, which she narrated in the meeting. The English translations are more terse in the videos, given the demands of the format.

The photographs and video material constitute, I think, other sorts of invitations to participate in the work of mourning undertaken by the Macotera-Pizarro and Rivas-Torres families.

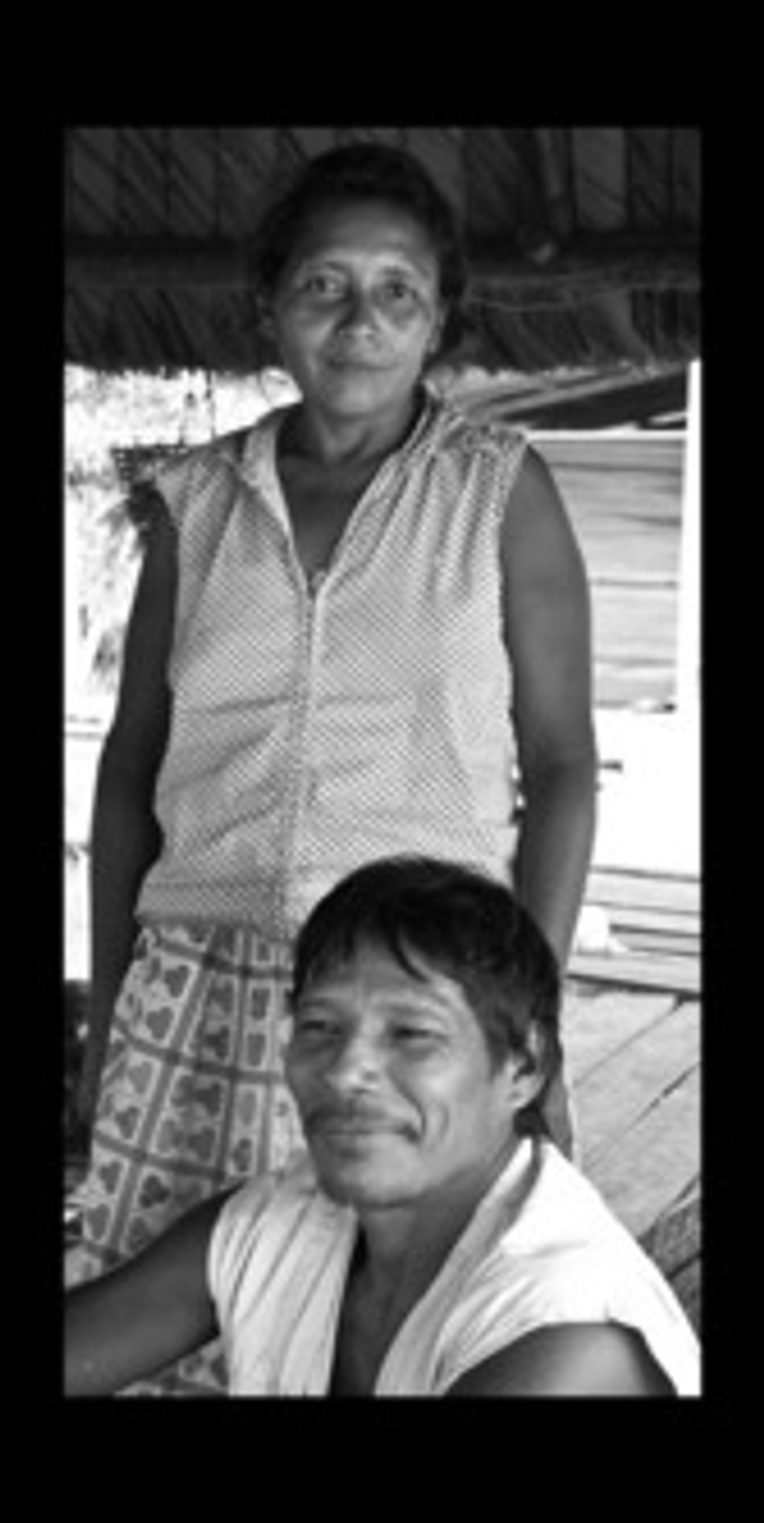

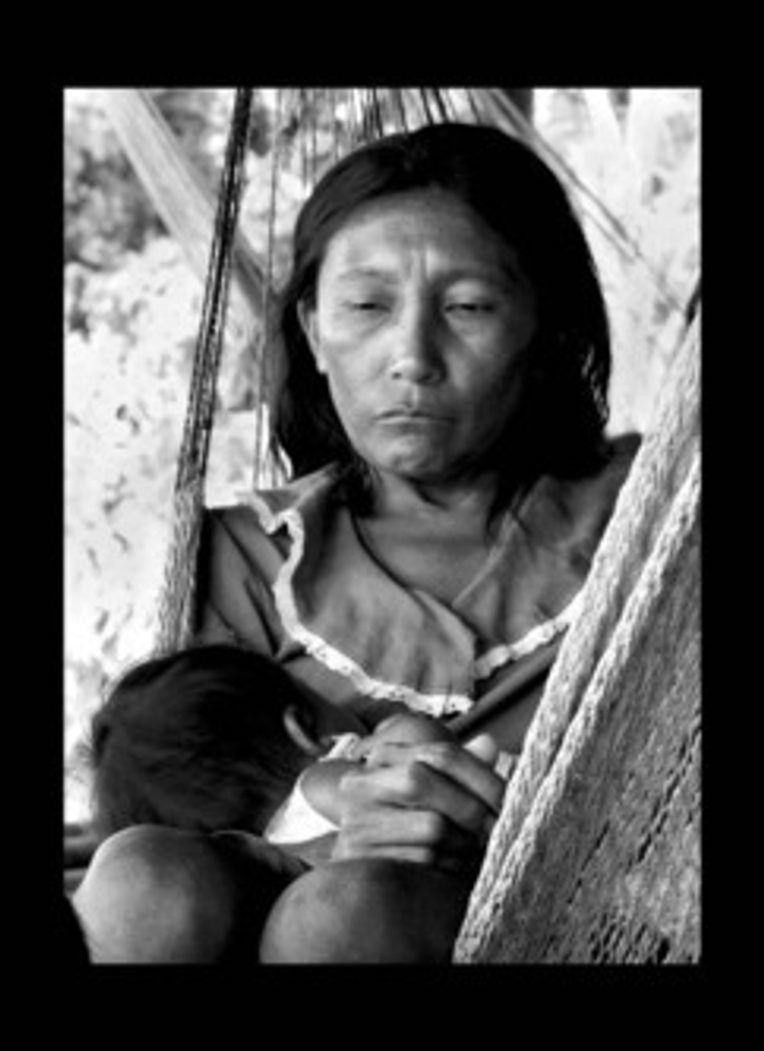

Elbia Torres Rivas of Barranquita

Tell Me Why My Children Died!

Parents from other parts of Delta Amacuro

Questions for Classroom Discussion

1. In his letter, Charles Briggs tells Freud that he would have liked to see Freud attend to the role of poetics in testing the reality of loss (4). Why might this be important? What does the semiotic process of poetics allow us to do that other forms of representation cannot?

2. One of the ways Briggs shows us that mourning can jump spatial-temporal scales from personal loss to social death is through photos. The images he presents in the letter and in the photo essay above are a powerful demonstration of the way lives and roles can be reframed by the indexing effect of visual representation. How do you see the visuality of these images as related to the aurality of the laments of mourning which Briggs discusses in the letter? Are they a kind of translation across sense registers? Is a poetics of reality testing as necessary in the visual as it is in the laments?

3. One of the most evocative poetic images in the letter comes in a form of a quotation from Juan-David Nasio regarding our affective attachments with those we love. Nasio tells us that we cover our beloved as “ivy covers a wall” and, Briggs adds, the process of mourning involves a retracing of these intimate attachments (9). Given the necessity of this depth of feeling, what are the implications of mourning the loss of the unloved? To what extent are the lives of strangers—those we don’t know deeply—grievable?

4. Building further on this last question, if anthropology is “the work of mourning,” as Briggs suggests (24), is the task of anthropologists that of making the losses of strangers grievable to our colleagues, readers, and students? Or does this repointing of anthropology stress an openness toward the needs of the precarious lives we encounter through our work?