“Diaspo” Youth Culture and the Ivoirian Crisis

From the Series: Côte d'Ivoire Is Cooling Down? Reflections a Year after the Battle for Abidjan

From the Series: Côte d'Ivoire Is Cooling Down? Reflections a Year after the Battle for Abidjan

Jesper Bjarnesen, Department of Cultural Anthropology, Uppsala University

In the commercial center of Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso’s second largest city, one of the most successful mobile phone vendors goes by the nickname, “Wassakara,” which also adorns the facade of his shop, remarkable for its bright red and white colors and display cases which contain all the latest model phones in an array of colors and brands. Across the border in Côte d’Ivoire, “Wassakara” is the popular name for Abidjan’s Yopougon neighborhood, known for its emblematic nightlife and celebrated in Ivoirian pop culture.

Aliou “Wassakara” is not alone in exploiting his Ivoirian upbringing to distinguish himself from the competition. He dresses in fashionable street wear that he buys second-hand, rather than wearing the tailor-made shirts in local fabrics associated with Burkinabe youths. He uses handshakes and mannerisms that originated in Abidjan and speaks French interspersed with nouchi slang, which has become a signature of Ivoirian pop culture [1]. Nouchi figures prominently in many of the Ivoirian pop songs and music videos being consumed by youths in Côte d’Ivoire’s poorer neighbors: Burkina Faso, Guinea, and Mali. Aliou “Wassakara” calls himself a “Diaspo,” a word that has its origins in the university circles of Ouagadougou, where the children of wealthier Burkinabe labor migrants in Côte d’Ivoire have been sent to escape the instability prevailing in Ivoirian higher education since the 1980s [2, 3, 4, 5].

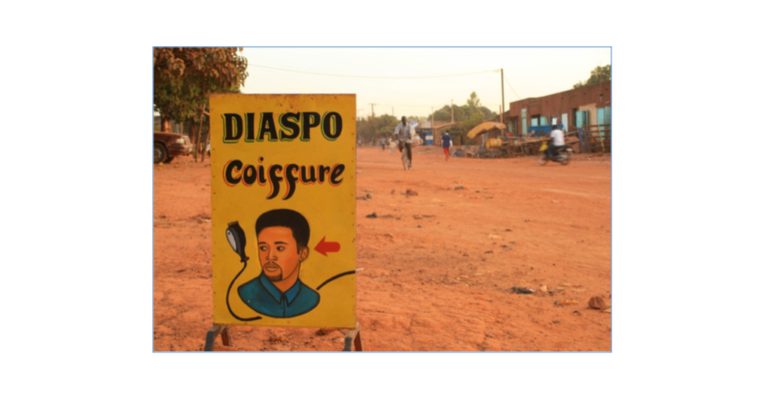

In the past decade “diaspo” youths have become a visible presence in Bobo-Dioulasso. By displaying their Ivoirian origins, they have provoked both the admiration and resentment of local youths, who prefer to perceive the outspoken and colorful newcomers as arrogant and disrespectful. But regardless of these animosities, “diaspo” youth culture has made its mark on the city. From the elaborately decorated shops in the city center to the proliferation of brands like “Diaspo Coiffure” hairdressers or “Diaspora Révélation” tailors, “diaspo” has become a brand associated with the regional metropole, Abidjan (Figures 1-3).

This perceived intrusion of “diaspo” youth culture into Bobo-Dioulasso is only one way in which the Ivoirian crisis has changed the meanings of transnational mobility between Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire. A significant part of the last decade’s building boom is attributed to the investments of high-ranking rebel commanders and Ivoirian businessmen who moved their capital to the more stable economy across the border. New night clubs, transportation companies, office buildings, apartment complexes, and luxury villas have appeared, some of them halted, mid-construction, as testimony to the disintegration of the rebel war economy in northern Côte d’Ivoire.

Before and after the attempted coup of September 19, 2002, rebel recruiters held secret meetings in Bobo-Dioulasso, recruiting young Burkinabe men into the Forces Nouvelles rebel movement. In various ways, the Ivoirian crisis has both shaped the city’s appearance and altered people’s perceptions of cross-border movements.

It is in this context of wartime mobility that the forced return of “diaspo” youths and their parents should be understood. Non-migrant residents have experienced the arrival of several new categories of migrants: Ivoirian rebel commanders, opportunistic businessmen, returning Burkinabe rebel fighters, and large numbers of returning labor migrants. These new categories of migrants are associated with the ills of war and are seen as a strain on the city—socially, financially, and morally.

As opposed to the socially sanctioned return of the (ideally) successful labor migrant at retirement, the involuntary return of Burkinabe citizens during the Ivoirian crisis has generated new images of immoral migrant trajectories. The “Diaspos,” many of whom had never set foot in Burkina Faso prior to their forced displacement, are among the most visible. By embracing their labeling as a blessing rather than a curse, their public image challenges the stereotypical Burkinabe values of moderation and respectfulness. To some extent this perceived arrogance is proving to be an asset, as a source of both self-worth and cultural capital in gaining access to scarce employment opportunities in the city. In addition to the direct branding of shops and businesses, “diaspo” youths are finding their cosmopolitan linguistic skills and attitude useful in finding work as salespeople, radio hosts, bus drivers, and so on. As this brief example shows, wartime mobility in the context of the Ivoirian crisis has taken many forms, often with unexpected consequences.

[1] Newell, Sasha. 2006. Estranged Belongings: A Moral Economy of Theft in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Anthropological Theory 6 (2): 179-203.

[2] Mazzocchetti, Jacinthe. 2009. Être étudiant à Ouagadougou: Itinérances, imaginaire et précarité. Paris: Éditions Karthala.

[3] Bredeloup, Sylvie. 2006. Réinstallation à Ouagadougou des "rapatriés" burkinabè de Côte d'Ivoire. Afrique Contemporaine 1 (217): 185-201.

[4] Zongo, Mahamadou. 2003. La diaspora burkinabé en Côte d'Ivoire: trajectoire historique, recomposition des dynamiques migratoires et rapport avec le pays d'origine. Politique Africaine 89: 113-126. [Alternative citation: Zongo, Mahamadou. 2003. La diaspora burkinabé en Côte d'Ivoire: trajectoire historique, recomposition des dynamiques migratoires et rapport avec le pays d'origine. Revue africaine de sociologie 7 (2): 58-72].

[5] ------, ed. 2010. Les enjeux autour de la diaspora burkinabé: Burkinabé à l'étranger, étrangers au Burkina Faso. Paris: L'Harmattan.