This post builds on the research article “Dreamwork: Cell Phone Novelists, Labor, and Politics in Contemporary Japan,” which was published in the February 2013 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editorial Footnotes

Cultural Anthropology has published a number of articles on Japan, including Lieba Faier’s ‘Runaway Stories: The Underground Micromovements of Filipina Oyomesan in Rural Japan’ (2008), Miyako Inoue’s ‘The Listening Subject of Japanese Modernity and His Auditory Double’ (2003), and Anne Allison’s ‘Cyborg Violence: Bursting Borders and Bodies with Queer Machines' (2001).

Cultural Anthropology has also published a number of articles on media as a mode of communication, including Brent Luvaas’s ‘Dislocating Sound: The Deterritorialization of Indonesian Indie Pop’ (2009), Paul Manning’s ‘Rose-Colored Glasses? Color Revolutions and Cartoon Chaos in Postsocialist Georgia’ (2007), and Brian Keith Axel’s ‘Anthropology and the New Technologies of Communication’ (2006).

Interview with Gabriella Lukacs

Lindsay Poirier: When were you first exposed to the cell phone novel? What compelled you to pursue research related to this medium?

Gabriella Lukacs: Similar to other projects I have pursued, my interest evolved from a captivating image. In this case, the image was an ad I saw in Tokyo. It portrayed a high school girl lying on the subway platform helpless—her uniform torn and her nose bleeding. The image showed a man placing a novel titled Love Sky on her chest as an act of help. The caption read: “For those of you, who want to cry.” To me, the ad signaled a marked shift in mass cultural production. It did not conform to the criteria of good taste and light entertainment that consumers expect of mainstream advertising. It made me wonder what it meant that mainstream advertising embraced this odd configuration of violence and desperation. I wondered what kind of entertainment these novels might offer and why would high school students be interested in reading them. Later, I learned that Love Skywas based on a cell phone novel.

LP: In your essay you mention how the pervasiveness of mobile technology has been a factor in the sudden popularity of writing cell phone novels. In your opinion, what aspects or qualities of this particular technology make it effective for writing and disseminating novels? What aspects make it effective for enticing young people to write novels? Can you cite any areas where the mobile technology is ineffective?

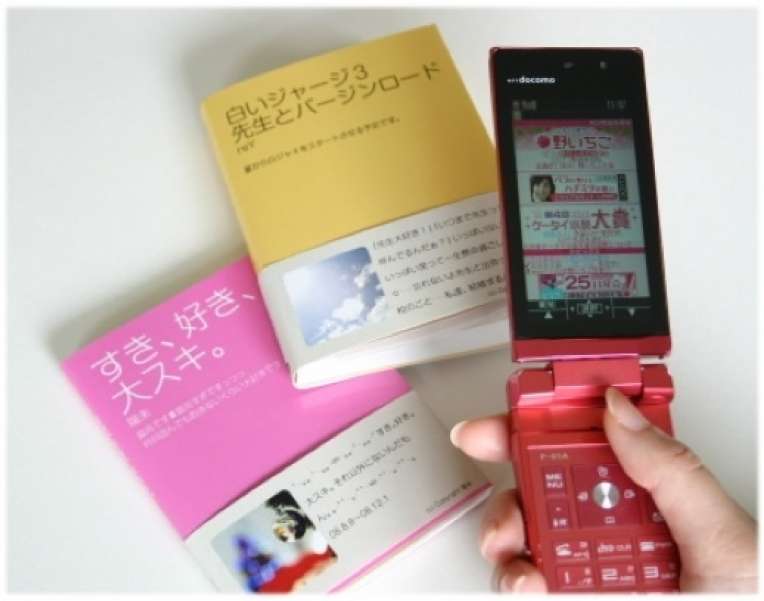

GL: Cell phones are an intimate part of young people’s lives. While this observation is not unique to Japan, I would like to highlight that Japan has been in the frontline of developing cutting edge cell phone technologies. In 2001, when I began my fieldwork in Tokyo, text messaging was already mainstream practice. The Japanese began using cell phone technology to email or access the Internet a decade before North Americans did. This trend has a lot to do with the excessively long hours the Japanese spend on commuting. Japanese people rely on their cell phones not only for communication, but also for entertainment and information. As a result, many of them think of their cell phones as intimate companions. They customize them with beads, sequins, stickers, and charms. They read novels on their cell phones before going to bed and use their cell phones to wake them up in the morning. Scholars noted that young people are more likely to exchange an endless number of text messages than to call each other on the phone.

I think that it is their intimate nature and their availability during commute that make cell phones conducive to writing novels. I cannot think of any prominent areas in which the cell phone technology is entirely ineffective, although I find it curious that it is still a text-driven (as opposed to being an image-driven) technology. Of course, there is a growing industry that specializes in developing games for cell phones, but in Japan the domestic television industry does not seem to be able to conquer this medium despite that networks started developing dramas for cell phones in the early 2000s. People are much more likely to read comic books than to watch television on their cell phones.

LP: In your essay you mention how, while the majority of labor markets are seeking to employ youth in ‘emotional labor,’ young people are tending to select to pursue ‘affective labor’ – in many cases without pay. In what ways do you see this affecting the Japanese economy? In what ways do you see it affecting the digital economy?

GL: The trend that young people turn to the digital economy in search of income-earning opportunities drives innovation in the architecture of this economy. In the essay, I demonstrate that while the first cell phone novelists had to create their own web pages to promote their novels, investors quickly developed novel portals with sophisticated applications that helped younger generations of novelists to write, disseminate, and promote their novels. These apps were developed in response to the popularity of cell phone novels and, of course, in search of profit. This pattern is not unique to the cell phone novel phenomenon. Initiatives by the young to earn an income in the digital economy are incessantly harnessed by investors of every stripe. Similar to cell phone novel portals that were developed to encourage young people to write novels, I see the same trend evolving in other contexts I explore in my new book project. Examples include the net idols who earn fame by posting their photos and diaries on the web, Internet traders who generate wealth from writing books about trading, amateur photographers who developed their compulsive documentation of “ordinary life” into an art form, and bloggers who emerge in the media as new models of professionalism. My feeling is that the digital economy is becoming a new frontier of experimenting with new mechanisms of producing surplus value.

LP: Have you found many youth to be discouraged by the unpredictability and precarity of the affective labor market? What do you believe will happen to the individuals who are unable to earn a living off of writing cell phone novels? Will they continue to pursue potential opportunities in this market?

GL: Work in the digital media economy is definitely precarious, and it is highly exploitative. Yet, it also reinforces what Paolo Virno called the “ideology of the possible.” This is an idea suggesting that the digital economy is the new frontier of endless opportunities. This ideology forces individuals to embrace “the habit of not having any habits” so that they can respond to those opportunities that unpredictably appear and disappear. Yet, as a successful videogame designer has pointed out to me, the digital economy ends up creating a culture of waiting—waiting for the opportunities to appear as opposed to creating those opportunities. While the digital economy offers fulfilling and lucrative work for a few, it locks the rest in regimes of underpaid or even unpaid work. However, young people are resilient. They do want to believe that they do have a future. They relentlessly seek ways to project themselves into the future in meaningful ways. In other words, my feeling is that most young people spend numerous years, even a decade, chasing “opportunities” in the digital economy. On their journeys, they learn new skills that, in some cases, they are able to invest outside of the digital economy.

LP: Your essay describes how cell phone novel portals provide an intimate space for forming social connections. Do you perceive any drawbacks to cultivating these relationships and promoting sociality through a technological medium? If so, what are they?

GL: Scholars talk about precarious sociality, which is a very interesting concept. My feeling is that the line between the “real” and the “virtual” is much more ambiguous than the way in which we currently understand it. When young people get support and encouragement online, it is much more likely that they will be more outgoing in real life as well. At least, this is what my informants have been telling me.

Questions for Class Discussion

1. How does Lukacs distinguish “emotional labor” from “affective labor?” What makes “affective labor” particularly attractive to youth in Japan? How might it become exploitative?

2. Describe how Lukacs portrays generation (youth vs. adulthood) throughout the essay. What historical, social, political, or economic factors may have played into the fragmentation of these two groups into distinctive spheres in contemporary Japan?

3. How does Lukacs’s portrayal of youth in contemporary Japan differ from that of other scholars?

4. What has factored into the success of the cell phone novel? Discuss the strategies employed by cell phone novel portals to generate content, readers, and writers. How have these strategies been supported by social factors or the nature of technology, and how has this impacted the popularity of the cell phone novel?

5. In what ways is the cell phone novel boom emblematic of the digital economy’s adoption of port-Fordist production?

6. How does the cell phone novel address the issue of Japan becoming a “society without relationships?” Discuss the role of the cell phone technology and how the nature of this technology affects both the ability to form social connections and the types of social connections that are formed.

Related Readings

Allison, Anne. "The Cool Brand, Affective Activism and Youth." Theory, Culture, and Society 26.2-3(2009):89-111.

Berlant, Laurent. Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011.

Driscoll, Mark. "Debt and Denunciation in Post-Bubble Japan." Cultural Critique65(2007):164-187.

Hall, Stuart. Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen, eds. London: Routledge, 1996.

Hardt, Michael. "Affective Labor." Boundary 2 26-2(1999):89-100.

Hoschild, Arlie Russel. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling.Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Mori, Yoshitaka. "Culture = Politics: The Emergence of New Cultural Forms of Protest in the Age of Freeter." Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 6-1(2005):17-29.

Muchleback, Andrea; "On Affective Labor in Post-Fordist Italy." Cultural Anthropology26-1(2011):59-82.

Terranova, Tiziana. Network culture: Politics for hte Information Age. London: Pluto, 2004.

Virno, Paolo. A Grammar of the Multitude: For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life. Isabella Bertoletti, James Cascaito, and Andrea Casson, trans. New York: Semio-text(e), 2004.