Enclosure

From the Series: Topology as Method

From the Series: Topology as Method

In June 2016, I came across images of the first of Taxi Fabric’s small number of public design installations in Delhi autorickshaws, a project undertaken in collaboration with Manas Foundation, which runs a government mandated gender sensitization program with autorickshaw and other drivers. The design, created by Nasheet Shadani and titled Tasavvur (imagination in Urdu), is organized around an image of Humayun’s Tomb, an iconic landmark in the city.

As installations, these designs are distinct from a painting, picture, image, or object in their composition as interiors, as curated assemblages of resonating colors, shapes, and images realized over a range of interior panels, seats, and aprons. During a conversation with a co-founder of Taxi Fabric, Sanket Avlani, he noted that one goal of the overall design project was to prompt, mediate, and sustain interactions between passengers and drivers, as a scene of civic recognition. In this sense, the design is meant to influence the quality of a relation by enclosing it. However, autorickshaws, unlike the taxis in Mumbai where Taxi Fabric began, are arguably more open than closed, having no doors, a high roof, and being easily entered and exited. Thus, the designs do not enclose by simply mimicking an existing architecture of enclosure—as Avlani suggested, the space they are meant to affect, though localized in the autorickshaw, also overlaps the interior of the city. Here, I offer a sketch of the material poetics of civic inclusion that the installations formulate.

As a platform for the design, the autorickshaw renders contingent encounters between a rider and a driver as a generic spatialized relation. The autorickshaw is the place in which a variety of individuals may literally enter and exit such a relation, in which a population of individuals circulate through its interior, giving that relation a general form and body. The circulation of autorickshaws, in turn, disseminates the relation throughout their overlapping spaces of transit, knotting their simultaneous localization of the relation in its general and particular form to diverse locations within the body of the city. Here, the relational architecture of interiors is a relatively simple one—the autorickshaw inside the city, the relation inside the autorickshaw, the people inside the relation. The design installation manipulates this nested architecture to enclose the city within the relation, without displacing that relation from inside the autorickshaw as the autorickshaw circulates inside the city. In this way, the designs give the city a civic character by placing the city inside itself. This manifests a more complex formal architecture of the mediation of interiority, which features of the Moebius band may illuminate.

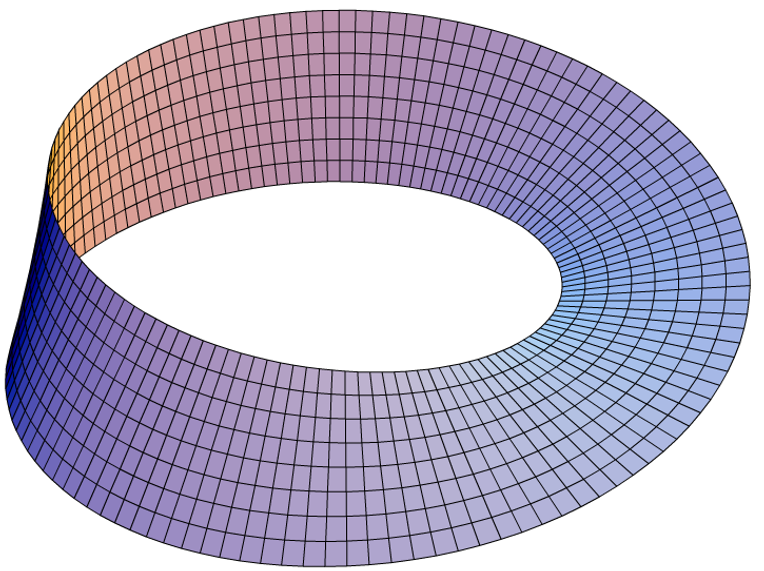

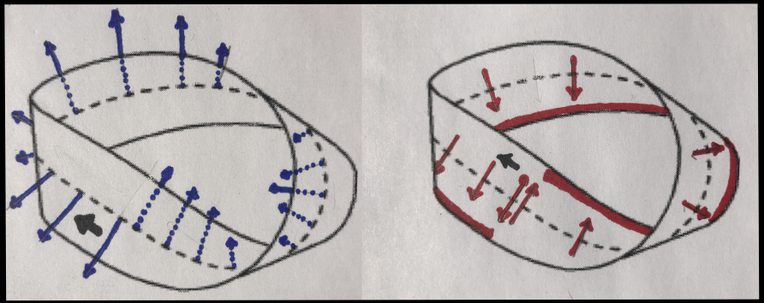

The Moebius band is a primary exemplar of the topological property of non-orientability, and placing it within a space (or, embedding it) can illustrate a number of counterintuitive spatial possibilities. In tracing a continuous transit across the length of the band, it is not possible to consistently determine orientation in terms of which side one is facing from point to point. Arrows or normal vectors drawn perpendicular to points along this line will progressively change direction along its path, twisting around until they face in opposite directions at the line’s origin—facing both sides in the same place.

However, the band is technically one-sided, and this twist appears only as a result of one type of embedding. This embedding can be modeled by fashioning a Moebius band from a ribbon, twisting it one-hundred and eighty degrees around its length and joining the ends together. Placing the band in a space in this manner shows how the twist which brings the two sides into relation is not an actual feature of the band, but rather an artifact of its embedding in that space. Additionally, if one takes an image of an arrow placed flat on the surface pointing to the left and moves it along the continuous line, it will appear as a mirror image of itself on return to the point of origin—facing right and left in the same place.

In both cases, the arrow appears to be facing one side and then the other without crossing any boundary. However, along with being one-sided, the band technically has only one boundary, and the mirroring can be taken as an expression of the twist in light of this fact. The image maintains a constant orientation to the boundary as the boundary twists, continuing to face it from the same side throughout, while being on both sides of the surface. The twisted boundary, topologically equivalent to a circle (a classic figure of enclosure), produces an interior, then, not by separating one side from another, but by differentiating two sides as continuously equivalent.

How, then, does the design installation’s poetic structure as an embedding of a Moebius band describe an apparatus of enclosure that may transform the city? The autorickshaw, through which persons circulate, and the city, in which the autorickshaw circulates, together constitute the band—the medium for the continuous transit of the generic relation in its continuous orientation to a single enclosing boundary. The generic relation, as localized intersection of these circulations, becomes an image of the interior of the vehicle on one side, and of the interior of the city on the other, the two sides rendered equivalent as being in the same place. The design installation is the twist, a technique of enclosure as transformation, and a non-localizable artifact of embedding, which arises from a total perspective on the interaction of embedded surface and encompassing space but is a feature of neither. The space in which the band is embedded is the set of relations civic inclusion might take, which the embedding actualizes in spatialized structures, such that the design may posit continuous interiority to the relation as a generic mode of the civic.