Engraved: A Family Forensics

From the Series: Review Forum on Writing with Light Magazine's Issue No. 1: Photography & Forensics

From the Series: Review Forum on Writing with Light Magazine's Issue No. 1: Photography & Forensics

“Circulated ‘as if’ they were evidence submissible to courts of law, forensic photographs—like human remains—are evidence of crimes. They are also something else...their ability to fluctuate between the poetic and the political, between the sensorial and the evidentiary, situate these images at a place where evidence and narrative intersect.” — Lee Douglas (2022, 25)

Can a network of images and objects, lost and found, tell us what the dead want? Or how to mourn them?

The photograph I’ve never seen is the one I know best. Most of what I have heard about it is muddled, even contradictory. But the photo has always been there: handed down as a story, offered as evidence.

According to my aunt, Frances Rosenblatt, the photo covers two pages of a book, with a break in the middle. On one side is a woman holding a child. A soldier is pulling the child away. On the other side, a man’s arm extends towards the woman and child, unable to reach them. “There’s a certain look to a desperate grasp,” says my aunt. The arm belongs to my grandfather, David Bialer. The child is Mira, his daughter, and the woman is Bella (Bajla), his first wife and Mira’s mother. The place is Łódź Ghetto, Poland, as families are being separated for deportation to concentration camps. It’s the last time my grandfather will see them. He survives the war, the separation. They do not.

Years later, my grandfather and another Holocaust survivor opened an engraving firm in New York City. In the mid-1960s, a man entered the shop and asked for my grandfather. He, too, was a displaced European Jew. My grandfather had sponsored his voyage to the United States through the organization HIAS (the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society). He gave my grandfather a book of photographs that he had taken during the war. Somewhere in it was this one.

Like me, my aunt knew about this photograph without ever hearing about it from my grandfather—to know about the photo was also to know his silence about it. She walked home from high school and found my grandfather’s car in the driveway. It was earlier than usual; he shouldn’t have been home then. He was in his bedroom with the door shut. He stayed there for hours. My grandmother, much more of a storyteller than he, explained later to my aunt what had happened.

There are other versions of this story, and they have complicated my attempts to find the photograph. I grew up hearing that it was in a museum exhibit the family visited (in New York in the 1960s, said my father; in Philadelphia in the 1980s, my sister thought). My grandfather saw the photo in one of the exhibit’s final displays. He stopped short, and left the room. In another version, the book of photos came in the mail. In all of the stories, it arrives unanticipated and unwelcome. It traumatizes my grandfather. He keeps it private in his desk drawer or on the shelves nearby. He dies, then my grandmother dies, and the house has to be cleaned out.

How terrible for it to be lost, this last record of my grandfather’s family together. How terrible that I might find it, that I am so hungry to find it.

Due to some accident of how information was delivered to me at a young age—and what my imagination did with that—I can now recall a time when this photo was the Holocaust for me. Something I never witnessed, but always the key referent. I think of how forensic anthropologists assemble an orderly narrative of horror out of messes of commingled bone, clothing, bullets. I think of stories of injury that are repeated over and over in courtroom testimony. As Elaine Scarry puts it, “no one hearing the story twenty-one times will, as they sense it about to resurface in its twenty-second iteration, be empty of the thought, ‘let it not be so’” (1985, 299).

The photo of Bella and Mira serves as evidence in my family. It is one of the most important images in our forensic archive, our shared understanding of what my grandparents suffered and lost. It is both an image we all carry with us (each one slightly differently) and a story of refusal: my grandfather’s refusal to explain, to make his grief a shared thing. It has come down to me as both the fact of suffering and a permanent indeterminacy of facts. A broken forensics, inadmissible in any court, engraved into my imagination.

Engraver—ingreyver in Yiddish, grawer in Polish, the languages my grandparents spoke at home. It was my grandfather’s occupation and how he survived the war. He was taken from Poland to Germany and forced to work at Sachsenhausen concentration camp as part of Operation Bernhard, a Nazi scheme to produce counterfeit British bank notes.[1]

For my Bar Mitzvah, he gave me a Cross fountain pen with my initials engraved on it. He would live only three more years, and his vision was already starting to cloud up with cataracts. His hand was growing unsteady. My initials wobbled a bit on the pen—they danced.

I was thirteen,

and stupid,

and we moved,

and I lost it.

No other object, this kind of ache. If I still had it, I would draw and draw with it, my own lines someday starting to shake.

Don’t copy, it’s cheating.

Don’t copy. You should cultivate your own style.

Don’t draw from photos; the drawings will come out static.

Nearly all the drawing I do these days is copying old photos—

learning them with my hand, using phototranscription

to touch people I’ve lost. Every mistake

is both a violation of memory

and a way of revealing

what was there in the photo

that I missed before.

I try again,

try to see better—

drawing closer

to the dead.

“So, where does a story begin? And if you are inside that story right now, in that situation and it hurts and say you can draw, then you must try and draw yourself out of it.” — Miriam Katin (2013, 9)

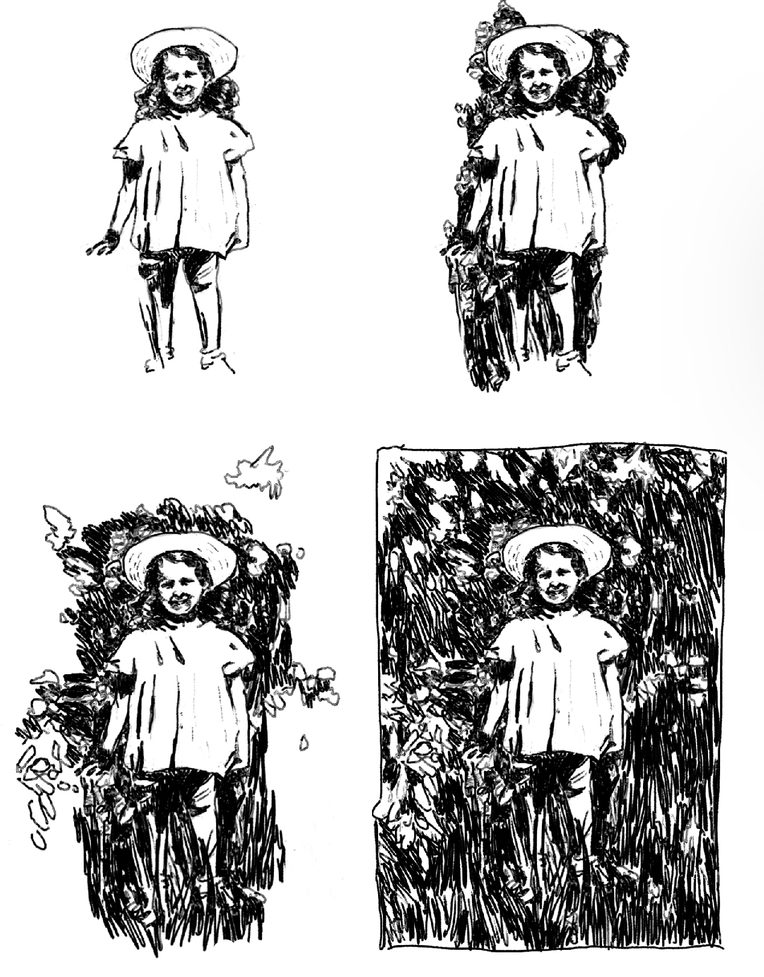

Besides the missing one, there’s one other photograph of my grandfather’s daughter, Mira. My grandmother passed it down to my sister. Mira is standing in front of a bush, wearing a straw hat. It looks as though the sun is in her eyes—they are hidden in shadow but still seem to squint. She smiles. Her face and short white dress pop out in high contrast, but much of the rest is confusion. Her hand might be holding onto a flower—it blends in too much to tell. I have trouble discerning the boundaries between her hair and the leaves behind her.

It’s a Persephone image: Mira’s face and torso are alive, bathed in light, but her hands and feet, and most of one leg, are being swallowed into the bushes behind her, her shoes merging into the grass below.

My first thought: it’s like she is already being buried, claimed by the earth.

My next thought: but she never had a real burial. Even my Persephone story is a comforting lie. I’ve imagined an underworld that would take in her little body, rather than confronting her eternal worldlessness.

In 1944, the year Mira died, Chelmno and Auschwitz-Birkenau were the two main camps used to exterminate Jews from the Łódź Ghetto.[2] In either place she would likely have been burned right after her death. Her ashes might then have been buried, used as fertilizer, or thrown in the Warta, Ner, or Vilna rivers.

When I drew the photo, I started with the parts of her I could see best: her hat, face, torso. Then I moved to the other elements: the bushes behind, the grass below. I watched as my own lines muddled her clear outline, as I disappeared parts of her. I’m still losing things.

I keep going down rabbit holes, into underworlds. I’m trying to find out what the name Mira means in Hebrew, in Yiddish, what it meant to my grandfather when he and her mother chose it for her. It might mean “prosperous,” “bitter,” or even “rising water,” like one of the rivers that swallowed all those ashes.

These days, I’m struggling through online Yiddish classes. But decades ago I learned a different language—a language I chose so that I could study how people disappear. In Spanish, mira is a verb, a command.

It means: look.

[1] On Operation Bernhard and the liberation of the prisoners after leaving Sachsenhausen, see: Malkin, Lawrence. 2006. Krueger’s Men: The Secret Nazi Counterfeit Plot and the Prisoners of Block 19. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

[2] We know the year of Mira’s death thanks to a plaque my grandfather donated to the Holocaust memorial room in the Diskin Orphanage in Jerusalem. It says, “In memory of my beloved daughter Mira and her mother Bella who perished in Holocaust 1944.” The plaque and a Łódź Ghetto registry with the family’s address, birth dates, and ages are all the information we have about Mira and Bella.

[3] The author would like to thank Frances Rosenblatt for sharing the stories that appear in this essay.

Douglas, Lee. 2022. Introduction to “Photographing Forensics: The Poetics and Politics of Spanish Exhumations,” by Clemente Bernad and Álvaro Minguito. Writing with Light 1: 24–39.

Katin, Miriam. 2013. Letting It Go. New York: Drawn and Quarterly.

Scarry, Elaine. 1985. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. New York: Oxford University Press.