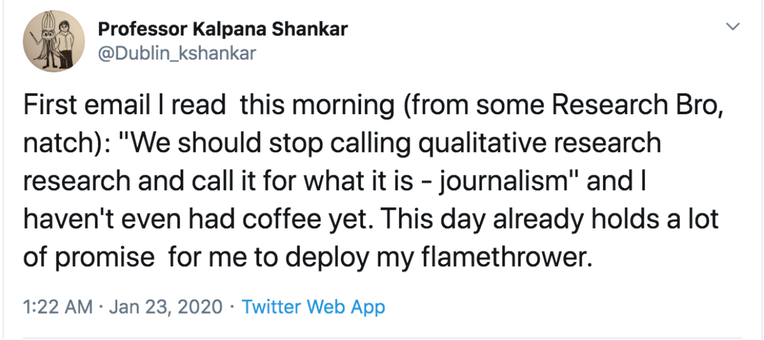

Qualitative research paradigms are often set in contrast to quantitative paradigms. And, in a lower-division anthropology class, students may only have familiarity with approaches to science and research that privilege a positivist, quantificational approach. Ethnography, as a research approach, encompasses a suite of research methods, frequently employing both quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis. Yet beliefs such as the one shown in the tweet above demonstrate that “qualitative” research is sometimes cynically viewed as a puffed-up way of saying “journalism.” These attitudes malign and mischaracterize both journalism and qualitative research paradigms, like ethnography.

Mary-Caitlyn was reckoning with some of these questions as she prepared the syllabus for a class titled “Latin America through Ethnography.” As a lower-division anthropology class open to both anthropology majors and non-majors, it was important to Mary-Caitlyn to address the importance and value of the “through ethnography” part of that title. What is ethnography? What value does it have as a mode of qualitative research? And in what ways is it different from journalism—if that’s all that qualitative research is, anyway (read with sarcasm!). Sydney suggested inviting students to read and critically assess paired sets of ethnographic and journalistic texts about the same event—and thus, this series of activities was born.

The following activities invite students to discover the value of ethnography as a research approach by comparing ethnographic research with journalistic work on similar topics through the recommended reading sets listed below. (Some of this work tackles topics that may require a content warning—we have provided sample text for this below). This comparative approach allows students to consider the politics of representing people, places, and problems through different epistemological and methodological perspectives. These activities were piloted in a class about Latin America, so most of the suggested readings are focused on ethnographic and journalistic texts based in/about that region. However, these activities could easily be adapted to similar sets of ethnographic and journalistic texts focused on other regions. The “orienting” texts—Deloria (1969), Wainaina (2005), and Jusionyte (2015)—have wider applicability. Please get in touch with us via social media if you have suggestions for additional sets of readings, discussion questions, or other strategies for adapting this activity to different teaching environments/platforms!

Learning Goals

- Define ethnography and journalism.

- Consider how issues of audience design shape the goals and conventions of both ethnography and journalism.

- Understand and be able to explain why anthropologists and other social scientists use ethnography as a methodological approach.

- Practice identifying different genres of data reporting, analysis, and narrative building around qualitative data.

Sample Text for Suggested Content Note

The assigned readings for our next class meeting address a case of genocide (and/or) harmful research practices (and/or) personal stories that may be difficult or uncomfortable to read. We will work to discuss these cases with responsibility and respect. Please be mindful of how you express your thoughts, and how your words might affect others. If you feel uncomfortable at any point during our discussion, you are free to step out of the room to decompress.

Recommended Reading Sets

Below are some sets of readings that include at least one journalistic account, one ethnographic account, and one text that includes perspectives of a member/s of the community under examination. There is also a set of “orienting” readings that speak more broadly to journalistic/ethnographic representation. Each activity plan requires a different subset of readings from the “orienting” set to establish the broader themes of the activity, so this set will not be assigned as a grouping, unlike the other text sets. We recommend picking one regional/topical set that best aligns with your class, and basing the discussions in both activity plans on these readings.

N.B. The El Mozote reading set includes a community-directed multimedia piece in Spanish. We recommend including this text, directing English monolingual students to resources on how to translate texts using online tools. This is a bit of a clumsy mechanism for including Spanish-language texts; we welcome recommendations from others who have successfully included non-English sources in their syllabi.

Orienting

Wainaina, Binyavanga. 2005. “How To Write About Africa.” Granta 92.

Deloria Jr., Vine. 1969. “Anthropologists and Other Friends.” In Custer Died for Your Sins, by Vine Deloria, Jr., 78–100. New York: Macmillan.

Jusionyte, Ieva. 2015. Savage Frontier: Making News and Security on the Argentine Border. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Recommended: Chapters 1 and 6]

Yanomami

Asch, Timothy and Napoleon Chagnon. 1987. Yanomamo of the Orinoco. Film. Watertown, Mass.: Documentary Educational Resources.

Borofsky, Rob. 2005. Yanomami: The Fierce Controversy and What We Can Learn From It. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Recommended: Chapters 5 and 6]

Tierney, Patrick. 2001. Darkness in El Dorado. New York: W.W. Norton.

El Mozote

Binford, Leigh. 2016. The El Mozote Massacre: Human Rights and Global Implications, Second Edition. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Recommended: Chapters 1 and 10]

Alarcón Medina, Rafael and Leigh Binford. 2014. “Revisiting the El Mozote Massacre: Memory and Politics in Postwar El Salvador.” Journal of Genocide Research 16, no. 4: 513–33.

Danner, Mark. 1994. The Massacre at El Mozote. New York: Vintage. [Recommended: Chapters 6 and 7]

El Faro. 2019. “Testigos: Las voces que hicieron sobrevivir a El Mozote.” https://mozote.elfaro.net/inicio.

Note: The video entitled “La vida que quedó” contains images of human remains from 8:59–9:20.

U.S.–Mexico Migration

De León, Jason. 2015. The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail. Oakland: University of California Press. [Recommended: Introduction and Chapter 2]

Holmes, Seth M. 2013. Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies: Migrant Farmworkers in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Recommended: Introduction]

Glass, Ira, host. 2019. “The Out Crowd.” This American Life (podcast). https://www.thisamericanlife.org/688/the-out-crowd

Guerrero, Diane. 2016. In the Country We Love: My Family Divided. New York: MacMillan. [Recommended: Chapter 3]

Class Activities

Below are suggestions for in-class discussion and activities. We offer plans for two activities. These activities are flexible: they can constitute two class periods, be condensed and combined into one class period, or be broken up across some digital method of communication and a synchronous (online or in-person) class meeting. Given the realities of online teaching right now, we also offer more detailed suggestions for conducting this entire lesson online in a separate section below.

Activity 1: Ethnography and Journalism

This activity draws on Jusionyte (2015) from the “orienting” reading set and whichever set of paired readings you selected to explore the differences and similarities between ethnography and journalism in terms of method and genre.

Part 1: Introductory Discussion + Optional Mini-Lecture

Before Class: Ask students to read Jusionyte (2015) chapters 1 and 6 (from the “Orienting” set) and be prepared to discuss their ideas.

During Class: Walk students through a reflection on Jusionyte’s experiences as a journalist compared to her experiences as an anthropologist.

- Possible questions to discuss include:

- How did her background as a journalist shape how she approached her ethnographic work?

- How does she characterize the difference between ethnography and journalism?

- What kinds of knowledge or truth production does she see as possible for journalism, and for ethnography?

Part 2: Making a Graphic Organizer

Depending on the size and format of your class, the following activity could be done in breakout groups or as a class, with the graphic organizer projected and visible to all.

Prompt students to generate a table, Venn diagram, or double bubble map that tracks the following characteristics of whichever set of readings you selected:

- What kind of writing or documenting is being done?

Expository, persuasive, narrative, descriptive? A bit of each? Something else entirely? - How did the author gather information?

- How long did it take the author to gather information?

- Who is the audience for the piece? How do we know?

- Does the author include any discussion of ethical dilemmas?

- What are the goals of journalism? Of ethnography? What are the strengths and weaknesses of each approach?

If students worked in small groups, ask each group to share their answer from one of the above questions, and record those in a graphic organizer that’s visible to the entire class.

Activity 2: The Politics of Representation

This activity draws on Wainaina (2005) and Deloria (1969) from the “orienting” reading set, and whichever set of paired readings you selected to explore how ethnography and journalism deal with ethical issues in reporting on and about people.

Part 1: Introductory Discussion + Optional Mini-Lecture

Before class: Ask students to read the Wainaina (2005) and Deloria (1969) materials (from the “Orienting” set) and be prepared to discuss their ideas.

During class: Have students discuss what Wainaina’s and Deloria’s pieces suggest about how non-white/non-Western groups have historically been studied and represented by researchers and journalists.

Optional (time allowing): Include a mini-lecture on the history of the darker side of anthropology, tracking anthropologists’ roles in problematic ventures from colonialism to the present day. You might include the following topics:

- Anthropology as the “handmaiden of colonialism”

- Extractive research practices

- Salvage ethnography

- Contemporary controversies, such as the role of anthropologists in the Human Terrain System program

Part 2: Case Studies

Building on students’ dissection of the journalistic and ethnographic examples in Activity 1, have them consider the following questions, either in small groups or as a class.

- Whose voices are included in the pieces they read?

- If it’s a written text, are any direct quotes used? Who is quoted?

- For video and audio texts, who is being interviewed?

- How is translation from one language into another handled?

- In the case of audio, is the original speaker’s voice covered by the translator’s?

- Are any images included?

- Who, if anyone, is being pictured? Individuals or groups?

If individuals, are they named? - What considerations might go into choosing whether to share the photographed person’s name?

- In what visual context is the person portrayed? How does that context impact your interpretation of the image?

- Who, if anyone, is being pictured? Individuals or groups?

- Who stands to benefit from the production of this work?

- Do you trust the accuracy of the account you’re reading? Why or why not?

Part 3: Reflection

Reflect on the discussions inspired by Activities 1 and 2. Consider the similarities and points of divergence between journalism and ethnography, and the issues of representation raised by both genres. Consider:

- What are the ethical obligations of ethnographers? Of journalists? In what ways are these obligations similar, and in what ways are they different? What strategies did the anthropologists and journalists use for representing the voices of community members in their work?

- To whom are ethnographers and journalists ethically obliged? What do they owe the communities they work with? What do they owe the audiences who engage with their work?

- How do the different goals/writing conventions of journalism and ethnography shape how journalists and anthropologists write about the communities they are engaged with?

- How should journalists and anthropologists decide what to say and not say about a community? Should journalists and anthropologists engage in advocacy on behalf of the people they write about? If so, how and when? If not, why?²

Adapting for Online Courses

We originally designed and piloted this activity in a face-to-face classroom. Here, we offer some suggestions for how to adapt these activities for online teaching.

- For a synchronous class structure:

- Proceed with Part 1 of each activity in a large group.

- Then, assign students to break-out rooms for smaller group discussion after Part 1. Many video conference platforms (like Zoom) have “breakout room” and “whiteboard” features. The whiteboard feature can be used for the graphic organizer activity (Activity 1, Part 2 above).

- For a hybrid asynchronous and synchronous class structure:

- Have students asynchronously annotate readings using a platform such as hypothes.is or VoiceThread (see if your institution has a subscription), using the discussion questions for each activity as a reading guide.

- Convene synchronously using Zoom or another video conferencing software to discuss their findings and reflect.

- For an asynchronous class structure:

- Offer Part 1 of each activity as a “mini-lecture,” and consider uploading these slides plus your “narration” to VoiceThread. The VoiceThread platform allows users to upload slides and add slide-by-slide narration, which other users can add audio, video, and text comments to, that are then visible to other members of the class.

- Give students a decent amount of time to watch and comment on your mini-lecture (perhaps a few days to a week, depending on the situation of your class).

- Assign students to small groups to complete the graphic organizer (Activity 1, Part 2) and case study (Activity 2, Part 2) activities. Using tools like Google Slides, they can collaborate remotely and asynchronously on slideshow presentations in which they demonstrate their graphic organizer/answers to some of the discussion questions.

- Ask each group to upload their slides to VoiceThread.

- Have students comment on/discuss each other's work to engage collegial collaboration in the activity.

- After viewing and engaging with the presentations of all groups, ask students to individually submit the Part 3 reflection in The Politics of Representation section (Activity 2) as a short essay/written response.

Points for Expansion

The readings and discussion prompts above could easily yield broader discussions about whose stories get told and how they get told. If you want to expand this topic into a broader unit, you might consider using other types of texts, such as songs, poems, literature, photographs, and other forms of art. Below are a few examples of other resources related to the above topics.

El Mozote

Dalton, Roque. 2005. No pronuncies mi nombre: Poesía completa. San Salvador: Dirección de Publicaciones e Impresos.³

Dalton, Roque. 1996. Small Hours of the Night: Selected Poems of Roque Dalton. Edited by Hardie St. Martin. Translated by Jonathan Cohen, James Graham, Ralph Nelson, Paul Pines, Hardie St. Martin, and David Unger. Willimantic, Conn.: Curbstone Press.

U.S./Mexico migration

Calibre 50. 2014. “El Inmigrante.” YouTube Video. Accessed April 1, 2020. . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v9zLchnWQcs

Los Tigres del Norte. 2009. “Tres Veces Mojado.” YouTube Video. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5mWAYZE1s10

Henríquez, Cristina. 2014. The Book of Unknown Americans. New York: Vintage. [Recommended: Chapter 1]

Urrea, Luis Alberto. 2008. The Devil’s Highway. New York: Hachette. [Recommended: Chapters 4, 5, 6]

Notes

1. Tweet shared with permission.

2. This and the previous question adapted from: Vargas-Cetina, Gabriela. 2013. Anthropology and the Politics of Representation. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

3. Thanks to Annalise Gardella for the excellent recommendation of Roque Dalton’s work.