What follows is an edited transcript of an interview that contributing editor Julien Porquet conducted with Denis Chevallier, Professor of Anthropology at University of Aix-Marseille, and Florent Molle, curator and head of the collection survey program at the Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilizations (MUCEM).

At the time of the interview, Florent Molle was working on the exhibition Nous Sommes Football (We Are Soccer), which explores social practices ranging from companionship and youth empowerment to hooliganism and violent outbreaks. Exhibitions like these offer insight into the audiovisual anthropological methods that contemporary museums use to engage new audiences. Located in between academia and the art world, the MUCEM tries to connect the two worlds through nontextual scholarship, by rethinking the ways in which videos, photographs, and objects can be exhibited. This interview explores the benefits and limitations of collaborations between artists and researchers, as well as the ethics of audiovisual documentation when working with people whose social practices are precarious.

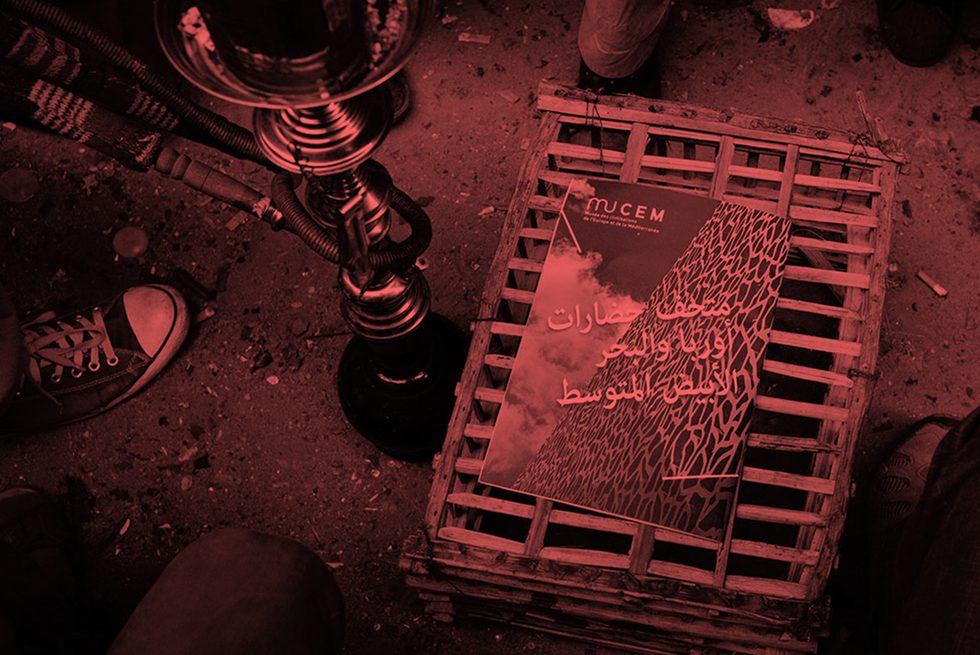

The MUCEM is the successor to the National Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions, which was created by museologist Georges-Henri Rivière in 1937. Ethnology in France has always been practiced collaboratively between universities and museums. The collections of the National Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions were therefore primarily formed by the use of collection surveys conducted in France by ethnologists. The idea was to send ethnologists to the field to collect artifacts, interviews, and photographs of so-called traditional practices, mostly in rural settings. The MUCEM, inaugurated in Marseille in June 2013, broadened its research areas so as to investigate the Euro-Mediterranean region. It aims to collect tokens of contemporary practices around the Mediterranean Sea through surveys, as well as to foster innovative collaborations between researchers, curators, and artists.

Julien Porquet: I understand that the surveys conducted by the museum are based on collaborations between researchers, curators, filmmakers, and photographers. Are all of those people conducting fieldwork simultaneously? What are the methods of data collection?

Florent Molle: The ideal group of people would be a curator, a researcher, and a photographer/director.

Denis Chevallier: And to have small teams. Depending on schedules it can be a bit complicated but usually we first do some pre-fieldwork. This is a first trip to see what can be collected, what is of interest, and to explain to people what we’d like to do. Then we come back with a team of photographers, among others, to collect the artifacts, videos, interviews, photographs, and so on. For the [recent] installation on Istanbul, researchers went to the field twice to check things out. They took photos and videos but that wasn’t perfect. So we came back with my cocurator Yann-Phillippe Tastevin and a director, and since we had already conducted the fieldwork, we were able to take all the pictures we wanted. So that was a three-step-process. But that’s the ideal and it’s not always possible.

FM: I worked on a project about the so-called ultra groups: soccer fans in Italy. I went with a sociologist-historian who specialized in the subject and, in that case, we weren’t able to show up whenever we wanted. There was only one opportunity to visit them. So we had to collect as much as we could during a single visit. We were doing everything without scouting, and we completely trusted the knowledge of the researcher, Sebastien Louis, who really knows the people. This allowed us to work in a more efficient way. But it’s true, the ideal is to have time, to return to the field a couple more times—that is, if we have the means. These days, it doesn’t appear to be profitable for a museum to conduct research [instead of just organizing exhibitions], so we have to fight that and make the case for the value of financing original research into these practices and objects.

JP: You worked with radical groups of soccer fans, so-called hooligans, and also with graffiti artists. How was this exhibition perceived by groups like these, which may feel misrepresented in the mainstream media?

FM: I cannot speak for the ethnologists, but as a curator, every time I conduct fieldwork, there is a discussion beforehand during which I explain who we are, what we do, and so on. Visiting people as a museum curator, rather than as a researcher, brings about a different kind of conversation, as people understand more readily what my role entails. When you say you're an anthropologist, they don’t really see the point in taking all of these photos and seeing them researched or exhibited somewhere else. It’s not an intuitive process. When I say I work for a national museum, there’s an immediate interest and understanding.

And this often comes along with comments like “now, your practices don’t exist in the museum, nobody preserves them and for us, it’s important to bear witness to this culture.” It’s true, the first time they saw us coming, they told us: “What’s with all the cameras, are you journalists? We don’t talk to journalists, as they always show the negative side of things.” So we had to clear that up. After this, everything ran smoothly. There are always places you can’t film, like the site where the ultras gather, because if it’s known by rival groups it could lead to conflicts. Yann-Phillipe Testevin used to say, “I return to the same fieldwork, but the relations are completely different,” because you have to negotiate the whole process each time. Sometimes there is money involved and you have to buy objects from the people you work with before you can exhibit them. But that is not the kind of relationship we usually have during fieldwork.

That’s when the trio of curator, researcher, and photographer works well, because curators work from a different worldview. They have a budget, and they are not as deeply involved in the fieldwork because they don’t have the same attachments as the ethnographer; sometimes it’s easier for them. I’ve seen this when I had to negotiate for an object. Sometimes the researcher would be telling me, “I can’t ask for that, I know it’s too important for them.” So I dared to ask more than an anthropologist would, because I didn’t have the same emotional bond. If we had to go to a rival group, the researcher couldn’t come because he was affiliated with a specific group, whereas I was meeting them in a much more casual way.

The goal is not to “burn” the field so as to collect items and objects for the museum. Rather, the goal is twofold: first, that the museum supports the research, and, second, that we become a showcase for the social sciences. Anthropology in France evolved alongside museums and, today, we try to keep in touch with the current trends within the discipline.

JP: Given how accessible audiovisual equipment has become, a growing number of people document their own everyday lives. How does the museum engage with such practices of self-representation?

FM: It’s extremely complicated because we would have to get the rights from YouTube or similar platforms, which is almost impossible. For the upcoming exhibition about soccer, there’s a section on hooliganism. There are some Russian fans who came to Marseille during the UEFA Euro [championship] in 2016, which resulted in huge street brawls with British fans. We wanted to talk about that and they actually recorded themselves with GoPro cameras and made homemade montages of the events. So we are showing some videos in the exhibition, but we obviously couldn’t get the permission of the person who filmed it, so we included an “all right reserved” notice [which allows the museum to use the content in an exhibition and the owner to ask for its removal if s/he wants to].

For an exhibition, such an approach will work, because it only last four months or so, but as a national museum, we can’t keep these audiovisual memories in our collection without the author’s approval. Let alone all the ethical issues it raises, especially for a video like this. The exhibition Lieux Saints Partagés (Shared Holy Places) raised a similar problem, as we showed a video of ISIS members destroying antique statues. Of course, we didn’t get in touch with Daesh to ask for permission. So this is not an area that we have been able to innovate in, because we are always dependent on the legal framework regarding intellectual property.

JP: Finally, what can we learn, as anthropologists working in academia, from what is going on in museums like the MUCEM?

FM: There are tons of links, of course. We have to recall that in the 1930s, Marcel Mauss was teaching his classes with the help of museum objects. I think these links always existed and have to be maintained. The researchers with whom I work have told me that conducting fieldwork for the museum “changes something in my fieldwork, there are things I take into account differently. I didn’t think about this notion of materiality, of the importance there is in knowing the time people put into making something, as well as the meaning it has.” To ask your informants to speak from objects and pictures is a method that brings a lot to the table.

I also think we can access different forms of data, because notions of savoir-faire, emotional time, etc. can only be reached in the presence of the objects themselves. For example, to get a banner [from an ultra group] was really hard because it’s such an important object; we never actually managed to do so. Long story short, the ultra group is united behind its banner, which is the first one that group made and behind which they sit in the grandstands. Thus no group has agreed to give us a banner, or even to sell or rent it. Even the groups that cease to exist cut their banners into pieces so that they don’t get stolen by other groups. Because going to the stadium with another group’s banner and turning it upside-down is a really violent act. Even though no media outlets are going to notice that during a game, it’s a really important act. So, here, the material aspect of the ultra’s life is fundamental.