“For He Will Kill You with His Horrible Sight”: Compiling the Belarus Political Book of Beasts

From the Series: Relating, Refusing, and Archiving Otherwise

From the Series: Relating, Refusing, and Archiving Otherwise

In 2020, following Alexander Lukashenko’s claim of a landslide victory in presidential elections, Belarus witnessed the most massive protests in its modern history. Peaceful marches against falsified elections were met with wired fences, military vehicles, tear gas, flashbang grenades, and unrestrained militia violence. One of the key factors enabling the scale of brutality witnessed in Belarus was the anonymity of militia employees—something that has always been carefully protected by the regime (Laneuski 2019).

Vehicles without license plates, paramilitaries with no badges or emblems, and police officers disguised as civilians are key features of the State Security Committee of the Republic of Belarus (also known as KGB). All of these are mobilized to avoid accountability and ensure the regime’s monopoly on violence.

As a response, anti-authoritarian movements have created and deployed a range of novel revolutionary strategies against this obscure figure of the state. One strategy which played a core role for protest politics was deanonymization: targeted attempts to reveal the concrete bodies hidden inside the glossy armors of law enforcement. Deanonymization was a key tool in the opposition’s tactical repertoire. It held the potential to make militia officers accountable for their crimes and to curb the violence.

Whereas in the United States deanonymization is used to investigate and prosecute the crimes of the police, in Belarus, deanonymization targets the government’s efforts to obscure its present crimes and their future traceability. Crucially, deanonymization efforts aim at the longevity of the Lukashenko regime. Not only has the regime been in place for the past twenty seven years—as long as Belarus has been independent—but there is already a clear succession line. The struggle over anonymity and deanonymization is thus one over the future of the regime.

One of the central narratives of the Belarusian deanonymization movement is that every single militia officer will be eventually identified and held responsible. As Cyber-Partisans, a network of oppositional Belarus hackers explained to Deutsche Welle (italics by authors): “We are sure that security forces have already understood that nothing will remain secret. Sooner or later, all information about their crimes will become public. We think that the most important consequence of data disclosure is the reduction of the probability of illegitimate violence in the future.” Nexta—one of the biggest oppositional Telegram channels—gave a similar ultimatum to the riot police: “bandit balaclavas will be torn off.”

A crucial goal of deanonymization is to strip from the state the statute of limitations shielding it from accountability. As a tactic, deanonymization does not only serve to identify particular people, but to underscore that justice is impending and inevitable. Thus, deanonymization functions as an archive: a bestiary. A bestiary is a medieval book that indexes various types of creatures and their behaviors in an attempt to guide a reader through ethical dilemmas. Its core ethical concern makes it especially relevant for thinking through the Belarusian opposition’s archives of deanonymization.

For instance, identified militia officers have their name,

place of work, home address, license plate, and phone numbers published

on the internet. As soon as officers are indexed in a bestiary, they are

exposed to multiple risks: their apartment leases are terminated, they

are denied services, and their family members have problems finding

employment (Isachenko 2020). Many have been forced to move to other

cities.

In his work exploring mythology, nineteenth century Belarusian

writer Jan Barščeǔski indexes the features of

Belarusian monsters. Werewolves, for instance, escape to the forest to

hide when shapeshifting. Just like his werewolves, Belarusian militia

officers must too withdraw from society once deanonymized.

In an effort to counter this, the Belarusian regime began to implement novel anonymization tactics and techniques that aim both at concealing officers’ identities and hindering retrospective deanonymization.

In the wake of the protests in 2020, a YouTube video became viral by claiming that there existed artificial intelligence (AI) software that could identify militia officers even with their balaclavas on. The video provoked deep panic among security forces, undermining morale, and leading to a series of layoffs. The author later confessed that the video was fake. Despite the fact that no such software existed at the time, the video led many to the conclusion that regardless of how long it will take, Lukashenko will perish and that those responsible for repressions will be prosecuted. In an attempt to avoid such fates, some left the militia ranks, burned their uniforms, and threw away their badges. Those who quit their jobs during that time faced persecution and harsh treatment from prison guards.

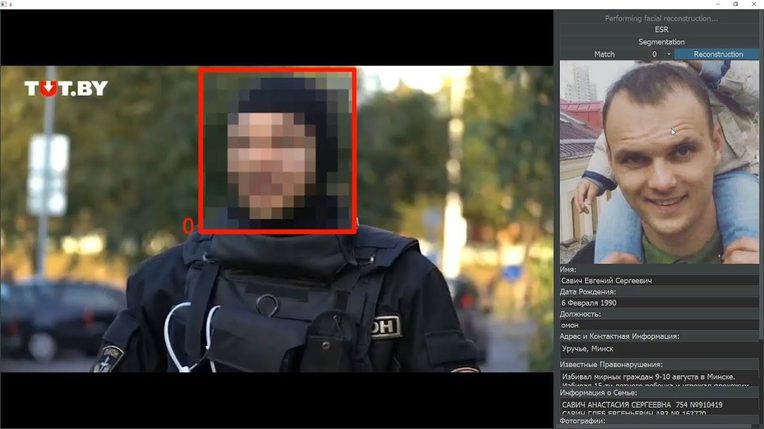

In 2022, the Association of Security Forces of Belarus (BYPOL) claimed in a video that their face recognition AI could identify the employees of the Special Purpose Police Detachment (OMON), even in masks (see fig. 1). Since the report did not feature the name of the software or any other details as to its workings, many people suspected it was merely speculation. Such a software would have required a dataset of images of officers with and without masks.

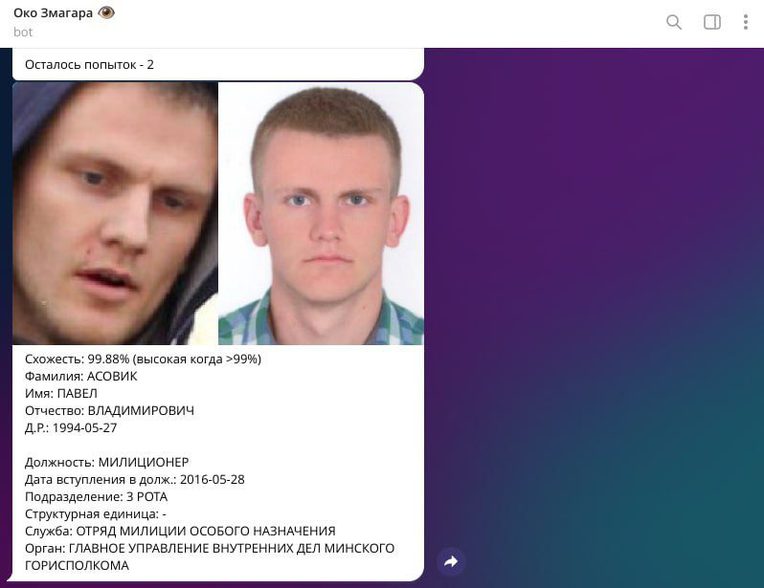

In April 2023, Cyber-Partisans—a Belarusian hacktivist group—released a face-recognition bot that drew on photographs crowdsourced through Telegram (see fig. 2). The software generated a similarity score between the database and users’ photo submissions and deemed a match reliable when the similarity score was ninety-nine percent or higher. Activists claim that this software was made possible through the aggregated materials collected through the Black Book of Belarus and the Punishers of Belarus Telegram channels.

These channels function like modern-day bestiaries: they systematize data in order to render monsters predictable, and thus devoid of their lethal capabilities. However, the first facial recognition software (described by BYPOL) was debunked shortly after its appearance. The Cyber-Partisans bot was deactivated after a few months without any commentary. While the online availability of personal information about militia officers and the existence of facial recognition software can prove useful for identifying police, they are of little help when confronting them in person.

In the courts, encounters between individuals prosecuted for not supporting the Lukashenko government and police are heavily mediated by technological and other anonymization measures. Notably, the regime has resorted to using fake witnesses (both militia officers and in some cases non-officers) as a means of speeding up the adjudication process. The courts have openly admitted that militia officers testify under the ‘witness protection system,’ which allows them to use aliases.

Fake witnesses are also granted protection and are separated from the crowd during, before, and after hearings (see fig. 3). They are brought to trials in a centralized manner and are escorted by militia to avoid face-to-face encounters with the crowd. Fake witnesses are also often moved to separate rooms and/or buildings. They are allowed to give their testimonies through Skype, often with their balaclavas on (see fig. 4).

Speaking in public means exposing their voice, pace and tone of speech, speaking habits, and body language—all of which could potentially facilitate their identification. As an additional measure, these witnesses are also protected with voice modulation software, which makes retrospective deanonymization effectively impossible.

In specific cases, additional anonymization measures are implemented. In small towns and villages, fake witnesses frequently risk testifying against neighbors, friends, or relatives. Thus, some hearings are relocated to other cities, away from the place of the residence of the accused. This makes it harder for relatives and friends of the accused to attend the trials, and decreases the probability of militia officers being identified either during or after trials.

Behind balaclavas, Belarusian officers become interchangeable and permutable, thus highlighting the need for bestiaries through which to trace their shapeshifting.

Militia officers are keen to hide their face because the face is the presumed threshold to public space. The face has the capacity to extend itself to other faces with which it is affiliated, carrying in itself an intrinsic threat of exposing a network of people (González 2009). On August 12th, 2020, when the situation was at its peak, Lukashenko awarded a group of security forces officials with special medals and diplomas “for impeccable service.” Not a single face is featured in the official report (see fig. 5).

All details that could give away the identities of the awardees were deliberately omitted. Instead, the images feature militia members’ hands, parts of their uniform, medals, diplomas, and flowers. This emphasis on body parts visually reflects the ways in which the militia serves as a set of disposable bodies for the regime.

When the protest movement had been slowed down and its last leaders were either arrested or forced to leave, the Belarusian regime faced the pressing need to continue producing propaganda for mass media while retaining militia employees’ anonymity. At present, all published images featuring security forces are thoroughly edited. The “Men with an Attitude” report on militia training published in the main propaganda newspaper Sovetskaya Belorussiya – Belarus Segodnya carefully avoids showing faces (see fig. 6). Militia officers either look away from the camera, hide their face behind objects, or have it edited during post-production (Gladkaya 2020).

Many images also show uncovered faces from a distance from which effective recognition is impossible. A significant number of photos are taken from the back. The majority of security forces employees have short haircuts. This makes them fuse into a dehumanized agent-smith-like figure (see fig. 7). Increasingly difficult to identify by others, militia officers remain recognizable only to their relatives and one another. Thus, such photographs may prove valuable as part of bestiaries and other databases.

The photo report from a review-competition of professional skills among OMON (riot police) features officers’ faces with erased facial features (see fig. 8). The original facial outlines are removed, making it impossible to identify the officers. Through such coverage, Lukashenko’s propaganda conveys an image of a faceless soldier. While Belarusian militia officers may enjoy the right to disappear, they are also made devoid of the right to be present and to have a face—and are thus denied subjectivity. They have no name, no ID number, and no possibility to withdraw. All in all, these photographs render Belarusian militia officers into non-human monsters who in the first place lack an identity to be identified.

To commit crimes in the middle of a city in broad daylight while retaining anonymity is an ambivalent yet core goal of the Belarusian militia. Belarus’s most notorious agency, the “Main Directorate for Combating Organized Crime and Corruption” (known as GUBOPIK) is the tactical group responsible for arbitrary mass beatings in the city center of Minsk. They wear regular clothes as well as tactical vests, helmets, gloves, shields, and batons. Equipped with military equipment and specialized vehicles (such as minibuses and highly maneuverable off-road vehicles without license plates), they move about ready to carry out public whippings while remaining difficult to spot.

Certain subdivisions of the Belarusian militia also perform surveillance at mass gatherings through filming and photographing. The phenomenon where athletic middle-aged men sporting short haircuts and civilian clothes openly carry video cameras has been known as tikhari—deriving from the Russian word [тихий], meaning “silent” (see fig. 9) since Soviet times. This name was used for law security forces officers (in particular the KGB) in civilian clothes, especially those who detained people. Despite their attempts to camouflage, the tikhari usually remain intuitively recognizable to protesters.

In one of Barščeǔski’s legends, several Belarusian villagers witness a shapeshift of someone they know into a werewolf. One of the villagers asks: “What is wrong with you? Why do you look so intimidating as if you were an animal?” Another villager replies: “Indeed, his eyes gleam like those of a wolf... Don’t look at him, my child! For he will kill you with his horrible sight.” The same gleamy wolf eyes that give the monster away are also the very source of its danger.

Barščeǔski, Jan. 1844. “Nobleman Zawalnia, or Belarus in Fantastic Stories.”

BBC News Russia. 2020. “Guys, it’s a shame.” YouTube, August 13.

“BlackBookBelarus.” 2020. Telegram Channel.

ByPol. 2022. “BYPOL Face Recognition System.” YouTube, January 12.

Cyber-Partisans. 2020. “Ultimatum to OMON.” (Telegram post)

EuroRadio. 2020. “How to Hide the Faces of the Best Minsk Riot Police (Photo).” Euroradio, November 24.

Gladkaya, Lyudmila. 2020. “In Minsk, OMON Fighters Passed Tests for the Right to Wear a Black Beret.” Belarus Today, November 13.

González, Jennifer. 2009. “The Face and the Public: Race, Secrecy, and Digital Art Practice.” Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 24, no. 1: 37–65.

Gotovko, Dariya. 2021. “In Minsk, a Review Competition of Professional Skills among Riot Policemen and Patrol Policemen Was Held.” Belarus Today, June 27.

Isachenko, Alina. 2020. “‘It's Time for Them to Think about Who They Are With’: Who and Why Unmasks the Belarusian Security Forces.” BBC News Russia, October 9.

“Karateli Belarusi.” 2020. Telegram Channel.

Laneuski, Aliaksandr. 2019. “The Militia and the Special Services in the Contemporary Politics of History of Belarus.” Institute of National Remembrance Review 1: 219–63.

Maximov, Andrew. 2020. “AI Unmasks Secret Police.” YouTube, September 24.