Framing the Otherwise Underground

From the Series: An Otherwise Anthropology

From the Series: An Otherwise Anthropology

There exists an otherwise underground. It is a space in which, through exchanges of performance, praise, and validation, Black and Brown youth dancers come up against the ideas of criminality historically surrounding their being as racialized subjects (Muhammad 2011). Their humanity is contested. The false link between criminality and Blackness, or proximity to Blackness, is a result of processes of dehumanization. The category Human, as Sylvia Wynter (2003, 268) argues, is overrepresented by the shadow of a consuming, heterosexual, middle-class white man that requires the category of dehumanized other embodied in the racialized hierarchical orderings of humanity.1 Ethnography then must rigorously interrogate the Human to understand when and how otherwise(s) not predicated on these hierarchies come(s) into being.

I come to my work as an ethnographer after decades of taking the train. My positionality is a product of experiencing the realities of urban terror as a radicalized subject in late capitalism. It comes with feeling the loss of physical spaces, for expression and creativity, to be replaced with more police and respectability politics. Amid these layers of dehumanization, youth performers are exerting their being. Their relationship with the audience is what produces the space and holds the possibility for disrupting the false link between criminality and Blackness. I offer three frames for bringing this otherwise underground into view. As the frames are shuffled, I ask the reader to see this urban public space in its complex totality and question the political possibilities of the Human otherwise.

The evening sun is setting as I descend a staircase underground. I pay money to enter the space. It is an urban public space and thus smells of structural neglect and neoliberalism. There is paint peeling on the walls, garbage on the floors, and a severe rat infestation. Heavily armed police with assault rifles, dressed in Kevlar, and positioned at the entrances wait for farebeaters or terrorists.2 I descend more stairs to a platform waiting, among hordes of other people, for a public train. One of the oldest and largest public transit systems in the world, the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) is the larger infrastructural entity that manages public transportation.

A train enters the station. Once onboard, an automated voice announces, “Stand clear of the closing doors please.” The train begins to rumble out of the station. There are three or four young men dressed in fitted caps, sweats, and worn sneakers. One of them carries a portable speaker, while another scans the train for the police. Yet another asks standing commuters to step aside. Suddenly, I hear the customary oration, “What time is it?!” to which the other youth respond in unison, “Showtime!” They begin to hip-hop dance in the center of the subway car for one-to-two minutes ending with, “Clap it up, Clap it up. Show love, not hate. We accept quarters, pennies, nickels, dimes, EBT, food stamps, MetroCards, and even a smile.” Some people seem visibly uncomfortable as they hold tight to their belongings or let out dramatically audible sighs, never quite looking at—but instead through—the young men. But others meet the youth in their exertion of their being. Amidst their scattered and hesitant applause, the youth accept monetary donations, handshakes, or verbal encouragement from these passengers-become-audience. The youth then exit at the next station, vanishing onto the crowded platform.

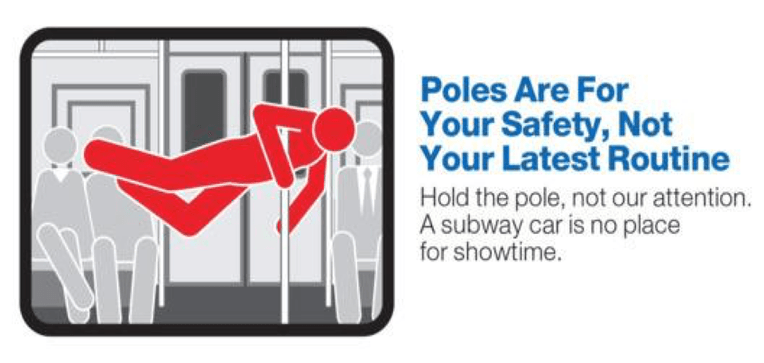

In 2015, the MTA launched a “Courtesy Counts” poster campaign. “Showtime” is the only busking activity explicitly targeted by the campaign, implicating it as criminal; it is also explicitly targeted by the New York City Police Department (NYPD) as a so-called “quality-of-life” issue. Both forms of policing operate under the dehumanizing association of Black and Brown (male) youth with the potential for criminality. This false link then leads to the very real fact of over-representation of racialized male youth as criminal. Showtime performers put this distortion of the category Human on view in the public transit places where they perform.

By studying what Faye Harrison calls “ex-centric” space—the area where theory and practice form a symbiotic relationship—we can “democratize and decolonize Northern landscapes of knowledge production” (Harrison 2016, 170). The subway offers up such a space where knowledge production occurs in multitudes. In their exchanges with passengers-become-audience, the urban terrain within which these youth are laboring becomes an otherwise underground. The recognition of these Black and Brown youth performers as Human is political.

Underground and above, gentrification impacts Black and Brown youth through spatial displacement. Newly constructed luxury businesses and residences are both inaccessible to New York’s poor and working classes and take up space in their neighborhoods. This displacement is exacerbated through the hyper-policing of racialized youth in public housing and public schools—and on public transportation. People living in heavily policed communities adjust their behavior, relationships, use of space, or schedule to avoid police interactions (New York Civil Liberties Union [NYCLU] 2017). What contributes to a healthy and safe neighborhood? Participants in heavily policed communities list “good schools, well-paying jobs, youth centers, affordable, quality housing, and job training programs” (NYCLU 2017, 23).

The loss of these material conditions creates the terrain in which a young person has the potential to earn more in underground economies than through incorporation into the formal economy. Gentrification, thus, distorts and divides the category Human: into those with access to resources and those without, into those deemed worthy of humanity and those who are not. Within the otherwise underground, however, subway performers can break apart these hierarchies.

***

Showtime is a performative disruption that is rearticulated daily as part of the mundane. It tells the audience, “I’m here. I exist. I deserve to be here. I am gushing with creativity and energy despite these racist notions surrounding me.” The perception of these performers often vacillates between whether or not they should be criminalized. In fact, their humanity itself is always in question. Yet, for every moment of praise and validation, every instance in which these youth are humanized, an otherwise comes into being forcing passengers to experience this public space—and the category Human—differently.

1. Wynter contextualizes racialized youth in the United States as part of les damnes-internal, stating the United States is “coming to comprise the criminalized majority Black and dark-skinned Latino inner city males now made to man the rapidly expanding prison-industrial complex, together with their female peers—the kicked-about Welfare Moms. . . both being part of the ever-expanding global, transracial category of the homeless/the jobless, the semi-jobless, the criminalized drug-offending prison population” (2003, 261).

2. A farebeater is an individual who does not pay the fare. In 2016, over 92 percent of individuals stopped by the NYPD for fare evasion were Black or Latino.

Harrison, Faye V. 2016. “Theorizing in Ex-Centric Sites.” Anthropological Theory 16, nos. 2–3: 160–76.

Muhammad, Khalil Gibran. 2011. The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime and the Making of Modern Urban America. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU). 2017. “Shattered: The Continuing, Damaging, and Disparate Legacy of Broken Windows Policing in New York City.” New York: NYCLU.

Wynter, Sylvia. 2003. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation: An Argument.” The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3: 257–337.