From Polder Colony to Greenhouse Plantation: Dwelling in the Noordoostpolder Plantationocene

From the Series: Plantationocene

From the Series: Plantationocene

The following is a visual essay on the living spaces of contemporary migrant workers in a Dutch polder. Drawing on historical and satellite imagery as well as field visits, we chart how the spatial, extractivist, and colonial logics of the high-tech plantation are currently replacing earlier biopolitical models that had inscribed nuclear family farms and farm worker communities in the polder landscapes of the Netherlands.

This is a “migrant worker park” (arbeidsmigrantenpark) for seasonal laborers in Noordoostpolder, the Netherlands. With the arrival of warehouses, logistics centers and large-scale greenhouse horticulture to the area, temporary work has become available throughout the year. Those inhabiting this space are provided with all the basic conditions to facilitate their lives: a “dignified dwelling” with “privacy and comfort’” and basic amenities, like television and Wi-Fi (Anon 2022).

The site initially offered living space for 300 temporary workers in 150 cabins, and has been extended by filling empty spaces with caravan units. An employment agency manages the worker village and matches a flexible eastern European workforce to a range of regional employers. Resembling the character of the work executed in large warehouses and greenhouses, these living spaces are purely functional, brand new, and well-maintained; designed in a way that makes the transfer from one group of inhabitants to the other barely noticeable. There are basic private spaces of the cabin dwellings meant for couples. But shared spaces for leisure are also provided. These designated communal spaces however remain empty. Most free time is spent on doorsteps. Scrolling phones. Chatting.

The remote location offers limited possibilities for traveling to nearby towns, or opportunity to interact with locals. A mobile (Polish) pop-up supermarket attracts long queues in the parking lot every Sunday. For acquiring other products people try to reach the village centers in the area, even though mobility is limited. Sometimes bicycles are provided, or driving groups are made for this purpose.

Having previously worked in other temporary arrangements in Poland and Russia, Michal misses the chaos that gives a place a “soul,” and complains about how neat and structured the place is. The repetitive rows of houses, sometimes complemented with rows of container living units, make for a “new” living model where everything is just enough for a comfortable stay of a few months, without building a relationship with a place.

While some workers stay for a season, there are others who try to switch between different types of jobs for longer periods of time, engaging in a type of a full-time temporarity. Work in the arable fields requires the presence of workers for short harvest periods, but greenhouse horticultural companies growing tomatoes, peppers, or flowers rely on a continuous workforce with additional peaks depending on the intensity of the season, which is defined by energy prices and competition with agrologistics centers in other climatic zones.

Georgi and his wife are in their late thirties. Originally from Bulgaria, they are staying in a caravan unit, to engage in different types of work in the Netherlands for eleven months in a year, only going back for a Christmas break. Their free time is mostly spent at the table between the containers on a video call with their two children who are back in Bulgaria, taken care of by the grandparents.

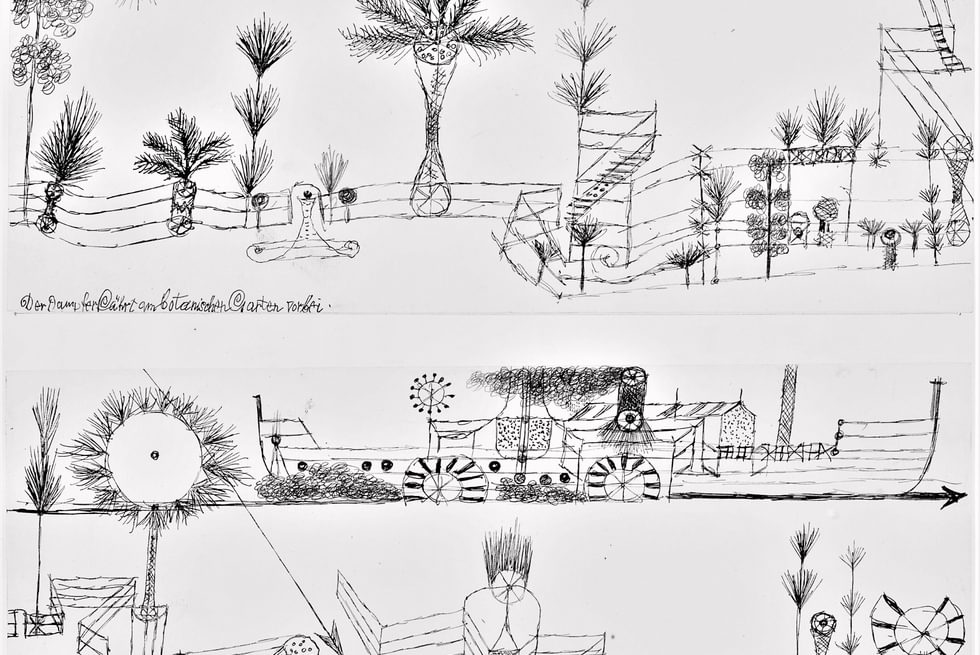

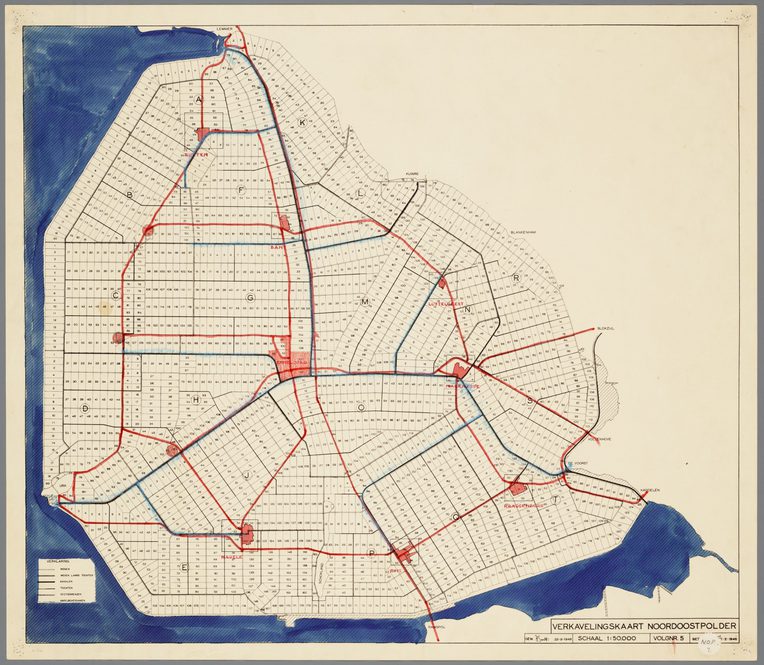

The worker village and the large-scale greenhouses they serve were only recently grafted onto a landscape pattern created for agricultural production under a different societal regime with another agro-biopolitical logic. Reclaimed from what had until 1932 been the open sea, in 1942 the Noordoostpolder was inaugurated as dry land: 48,000 fertile hectares highly suitable for arable farming. The land reclamation effort was set up by the Dutch government as a colonial project, seeking to optimize agricultural production by creating an ideal Dutch agricultural society.

Drawing on Central Place Theory (see Barnes and Roche 2022), 1,500 identical prefabricated concrete barns and farm houses, each with 24 hectares of land for independent family farmers, were complemented with ten polder villages for communities of farm workers at maximally one hour cycling distance from each farm and from a central town. A dedicated governmental planning authority actively sought to configure a particular combination of soil, crops, people, and social relations. Out of over 10,000 applicants for the available farmsteads, 1,500 nuclear families were selected by governmental inspectors, making house visits to assess farming knowledge, financial situation, housewife hygiene level, child discipline, and the presence of “pioneering spirit” (Vriend 2022).

The polder colonization program aimed to establish a new agricultural society based on modern agronomic and social sciences (Van de Grift 2013; Haartsen and Thissen 2018). Planning this new polder was extended to community formation. A series of conferences and reports (Ter Veen 1941; Van de Ven 1969; Venstra 1953) focused on the making of community, the building of solidarity, and how spatial planning interventions would contribute to the making of social unity.

The plantation is a particular configuration of plants and people, organized in space to benefit capital. Humans and nonhumans end up living in places they don’t really want to be; “forced” to come together in maximally productive relations. In the contemporary worker compound, people are mobilized by economic (and climatic, energy costs, and logistics) disparities among (European) regions. Haraway and Tsing (Mittman 2019) emphasize the Plantationocene as a global transformation into simplified agricultural ecologies, generating multispecies forced labor. They discuss the Plantationocene as a “process that breaks generations,” interrupting the possibility of intergenerational care. Moreover, they argue the plantation is radically incompatible with the “capacity to love and care for place.”

Overseas, the plantation was heralded as “the very core and seat of the structure of their ‘civilized’ values’” (Wynter 1971, 98). But in the original Noordoostpolder, as an explicitly experimental project of “internal colonization” (Van de Grift 2013), it was the hierarchy of independent farmers served by village communities of farm workers that were imagined to shape an ideal agricultural society. The current migrant worker compounds make the Noordoostpolder into a space “planted with people not to create societies but to […] produce single crops for the market” (Wynter 1971, 95) In this neoliberal production landscape, the ideal of planning for communities and building solidarity and connection to place is given up in favor of the temporary presence of people who are not deemed to be part of public life in the area (Aanjaagteam 2020), nor to have private lives other than those facilitated by minimal bodily comfort and hygiene.

Aanjaagteam Bescherming Arbeidsmigranten. 2020. Geen tweederangsburgers: aanbevelingen om misstanden bij arbeidsmigranten in Nederland tegen te gaan. Den Haag: Rijksoverheid

Anonymous. 2022. “Level One toont met Open Dag op nieuwe park Zwarte Meer inkijkje in huisvesting van arbeidsmigranten,” De Noordoostpolder, May 30, 2022.

Abma, E., & Montgomery, J. E. 1959. Woning, dorp en dorpsgemeenschap in de Noordoostpolder. Afdelingen voor Sociale Wetenschappen aan de Landbouwhogeschool.

Barnes, Trevor, and Michael Roche. 2022. “The International Circulation and Dissemination of Geographical Concepts and Ideas.” In A Geographical Century, edited by Vladimir Kolosov, Jacobo García-Álvarez, Michael Heffernan, and Bruno Schelhaas, 49–62. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

Haartsen, Tialda, and Frans Thissen. 2018. “Physical and Social Engineering in the Dutch Polders: The Case of the Noordoostpolder.” In Twentieth Century Land Settlement Schemes, edited by Roy Jones and Alexandre M. A. Diniz, 159–178. New York: Routledge.

Mitman, Gregg. 2019. “Reflections on the Plantationocene: A Conversation with Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing.” Edge Effects 12, June 18.

Ter Veen, H. N. 1941. “De kolonisatiepolitiek in den Noordoostpolder.” Mens en Maatschappij 17, no. 6: 353–378.

Van de Grift, Liesbeth. 2013. “On New Land a New Society: Internal Colonisation in the Netherlands, 1918–1940.” Contemporary European History 22, no. 4: 609–626.

Van de Ven, M. C. 1969. Taal in Noordoostpolder: een sociolinguïstisch onderzoek (No. 35). Stichting voor het Bevolkingsonderzoek in de Drooggelegde Zuiderzeepolders.

Venstra, A. J. 1953. “Kolonisatieproblemen in de drooggelegde Zuiderzeepolders.” Het Gemenebest Juli/Augustus.

Vriend, Eva. 2022. Het nieuwe land: het verhaal van een polder die perfect moest zijn. Amsterdam: Atlas Contact.

Wynter, Sylvia. 1971. “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation.” Savacou 5, no. 1: 95–102.