Graphic Ethnography: Tuning into the Melody

From the Series: Graphic Ethnography on the Rise

From the Series: Graphic Ethnography on the Rise

Illustrations by Ben Thomas

“If you don’t have the data and you don’t have the story, you don’t have what it takes to move people” —Brené Brown

I love hearing and telling people’s stories. That is what has drawn me to research. I believe that for anthropology (or any discipline for that matter) to be effective in engaging diverse audiences in the research it produces, it needs both the data and the story to communicate in a way that moves people. For me this has meant seeing my ethnographic research beyond the "finished, refined products of fieldwork: book or ethnographic article" (Collins et al. 2017, 142), without forgoing the written text. Collaborating with digital illustrator Ben Thomas, I have embarked on a process I call "retrospective (re)presentation": using the visual to offer alternative modes of (re)presentation to the written ethnographic text (Rumsby 2020). Ben and I are illustrating ethnographic research which I have conducted into the modes of identity and belonging among children of Vietnamese descent who live in Cambodia as noncitizens. We are creating this "ethno-graphic" novel to illuminate the social realities underlying childhood statelessness and, importantly, to give the research back to participants in an accessible format. The focus of this article is to unveil the why and possibilities of using illustration.

When people share their lives with you, it is like listening to a score of music. All our lives consist of different tempos, beats, and notes that illuminate the contours of our experiences. Listening to children’s stories over the years, I have heard their lyrics but have felt and remembered the melodies within their stories ever since. The melody is what I have found hard to capture in writing.[1] Illustration enables those melodies to be heard; illustration is an invitation to listen with your eyes. By bringing these melodies into view, we can engage with the affective details embedded in stories that would otherwise go unnoticed, largely because they denote a subjective experience.

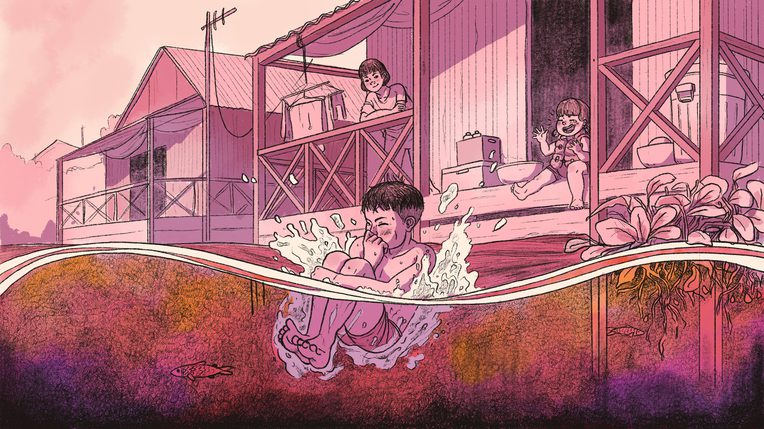

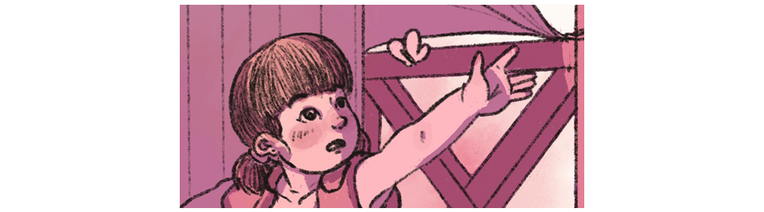

Illustrations are a way to document things I have and have not observed. They can transport the viewer in time through the (re)telling of life events, and they can invite the viewer to experience the emotional labour of someone’s memories in a way I think is different (not necessarily superior) to the text. The artistic direction I give to Ben in our collaborative work is rooted mostly in interview transcripts (the lyrics). Other experiences can be brought to bear through drawings. The conviviality of play (see image 2), and the emotions that hang in the air when difficult experiences of violence, death or trauma are shared.

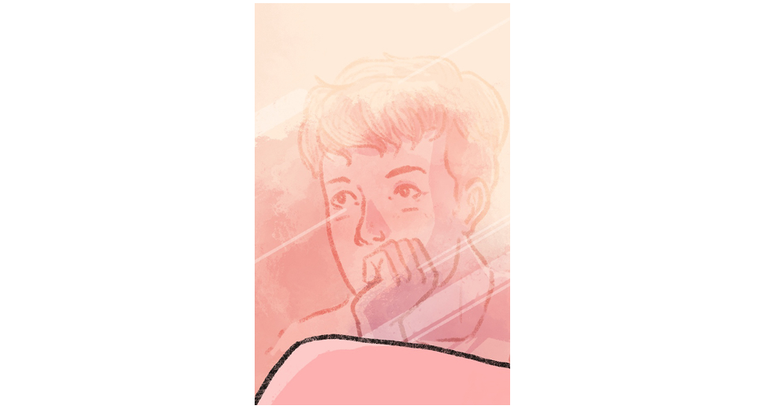

Image 1 represents the beginning of a memory told to me by a participant. Their first memory, which detailed the death of a sibling whilst in their care. During the research process I used visual methodologies selected by participants to explore themes they had chosen to discuss during the research period. This included the use of timelines to talk about the past and the future. Children’s first memories included being bitten by dogs or having fun visiting relatives. I asked Ben to draw the bus scene to denote travel. Time travel. This references the timeline past methodological tool used in research, and how memories are carried with us throughout our lives. During one interview, a child recalled

When I was 7 years old my younger sister fell into the water and died.

She was 3 years old. That time I stay at home to do to the housework, I brought her the life jacket, but she took it off. Nothing happened in my life until I am 7 years old. Then my sister died.

The drowning incident occurred when the participant, who was 14 years old at the time of the interview, was 7 years old. This story was not the first of its kind I had heard. Many people have fallen into the river and died. In some ways, by retelling this story, Ben and I are telling those other stories of loss.

Illustration offers the possibility of depth; each image will have something about it that speaks to the viewer. Without words, Ben was able to illustrate the recounting of a memory and its emotion. As in image 1, deep thought, and contemplation are embodied in eyes gazing off into the distance. Sadness is shown with a downturned lip. In image 5, the creases under the eyes, express the weight of the memory.[2]

Image 6 has a detail not in the interview transcript. The butterfly speaks of the mystery of the circumstances of this death. Butterflies have short but magnificent lives and speak to the fragility of this life. They have an endearing quality that easily enraptures. Much like a toddler.

The morose nature of stories, like the one shared in this piece, can be retold using the written word. I have done so myself (Rumsby 2017). Yet, we can bring to life issues of precarity and inequality in ways that differ from having people read a report or ethnographic article.

We can symbolize the unknown and build stories in a way that is "not dependent on text to create context for imagery, but instead if text is used it is an integral part of or even incidental to imagery" (Dix and Kaur 2019, 92). This builds accessibility, and desensitizes data from its often impregnable academic language. Through graphic anthropology we can move people to deeply consider the melodies beyond the words that make up the stories we tell.

[1] I first heard the metaphor or lyrics and melody in Podcast where Dan Pink discusses his research into regret. Accessible online at https://brenebrown.com/podcast/the-power-of-regret/#transcript

[2] To view the whole story, in sequence see https://www.charlierumsby.com/waters-of-death-and-life

Collins, Samuel Gerald, Matthew Durington, and Harjant Gill. 2017. "Multimodality: An Invitation." American Anthropologist 119, no. 1: 142–146.

Dix, Benjamin, and Raminder Kaur. 2019. "Drawing-Writing Culture: The Truth-Fiction Spectrum of an Ethno-Graphic Novel on the Sri Lankan Civil War and Migration," with illustrations by Lindsay Pollock. Visual Anthropology Review 35, no. 1: 76–111.

Rumsby, Charlie. 2017. "Researching Childhood Statelessness." In The World’s Stateless Children, edited by Laura van Waas and Amal de Chickera, 531–538. Oisterwijk: Wolf Legal Publishers.

Rumsby, Charlie. 2020. "Retrospective (Re)Presentation: Turning the Written Ethnographic Text into an 'Ethno-graphic.'" entanglements 3, no. 2: 7–27.