This post builds on the research article “Here Come the Anthros (Again): The Strange Marriage of Anthropology and Native America,” which was published in the May 2011 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editorial Footnotes

Cultural Anthropology has published a number of essays on Native American indigenity, including Jessica Cattelino's “The Double Bind of American Indian Need-Based Sovereignty” (2010), Andrea Muehlebach's "Making Place" at the United Nations: Indigenous Cultural Politics at the U.N. Working Group on Indigenous Populations” (2001), Pauline Turner Strong and Barrik Van Winkle's “"Indian Blood": Reflections on the Reckoning and Refiguring of Native North American Identity” (1996), and Theresa D. O'Nell's “Telling about Whites, Talking about Indians: Oppression, Resistance, and Contemporary American Indian Identity” (1994).

Interview with Orin Starn

Emily Levitt: Is there any room left for the exotic anywhere in anthropology? Can there be any innocent exoticism?

Orin Starn: Anthropology is always the study of the exotic, in the sense that culture everywhere is a strange, artificial, unlikely conceit. I’ve just finished a book about Tiger Woods and his place in the strange American kabuki theater of scandal, sports, and celebrity (The Passion of Tiger Woods: An Anthropologist’s Report on Golf, Sex, and Race in America, Duke University Press, 2011). There’s nothing more exotic than golf with its proverbial plaid pants and elaborate etiquette, or for that matter ritualized drama of the latest celebrity scandal. So, yes, there’s plenty of place in anthropology for scrutinizing the exotic, but not in a way that returns to the old primitivist imagination that fixed exoxticism as somehow unique to tribal peoples far out in the planet’s mythical far corners.

EL: The anthropologist of the early 20th century plays a very difficult role in modern anthropology. That figure is now generally depicted as an instrument—if not an agent (however those two words might be interpreted,)—of imperialism, to the point where any individual motivations they might have had are rarely addressed, and their colonial instrumentality is fore-grounded. Is there a potential space for opening their work up to a different level of study, one that allows for their own motivations?

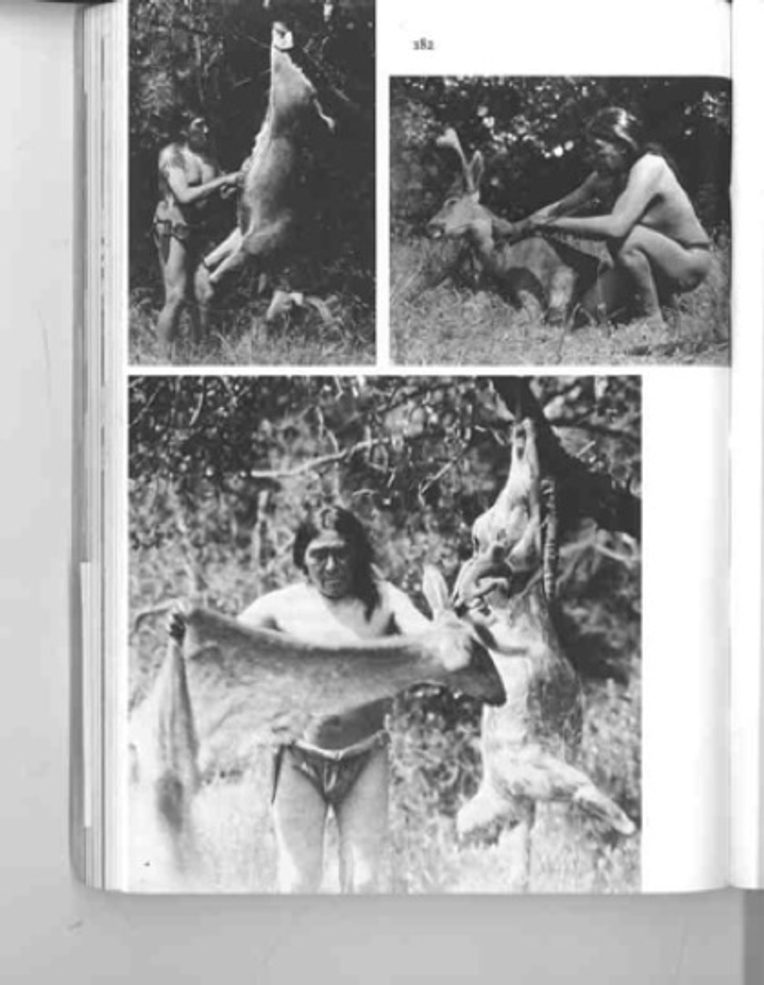

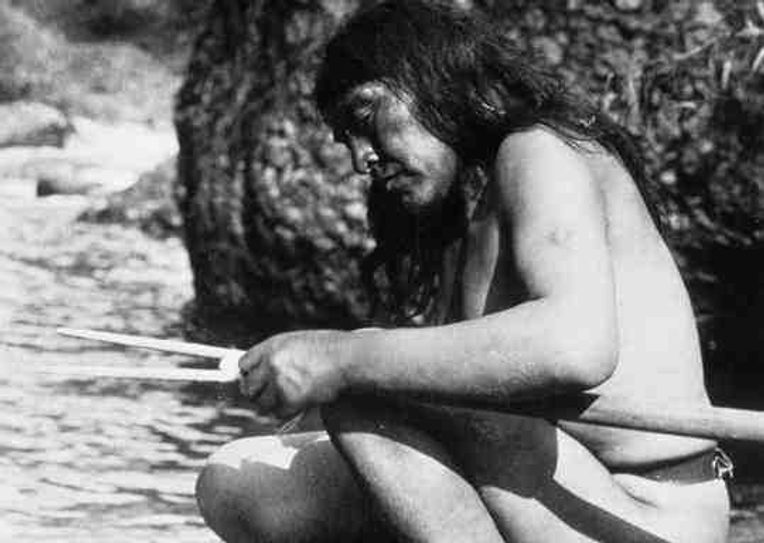

OS: Yes, the assumption that all the old anthropology was evil, colonial, unreflexive, complicit with power and so forth has become tiresome. It can be self-congratulatory in its suggestion that we are such a great improvement on our disciplinary ancestors, and it’s historically lazy in its failure to grapple with anthropology’s history in a more probing, fair-minded way. I may be guilty myself, as some of my earlier work was quite harsh about anthropology’s record, albeit saying some things I think needed to be said. The best scholarship in the history of anthropology goes far beyond the caricatures about anthropology as the handmaiden of imperialism. In my own last book, I tried to show the more dismal sides of the involvement of Alfred Kroeber and other anthropologists in the story of Ishi, the so-called “last wild Indian in North America,” and yet also the ways in which these men were ahead of their time in seeing beauty and value in native ways (Ishi’s Brain: In Search of America’s Last “Wild” Indian, W.W. Norton, 2004). I can’t say I’m quite interested enough to do it myself, but there’s a place for good biographies of some of the early anthropologists. Edward Sapir, a genius in his own way, deserves one. For that matter, I could imagine the life of a Bronislaw Malinowski or Margaret Mead as the stuff of a good arty Hollywood movie. As it stands, even as we like to imagine our greater enlightenment than our predecessors, cultural anthropology has a big public relations problem. Nobody outside the profession seems to have much idea just what we do. If they have any image of a cultural anthropologist at all, it’s of a khaki-wearing, notebook-toting researcher heading off into the bush to study the proverbial remote tribe. When I ask my students at the beginning of our large intro course to name a single living anthropologist, they’re either silent, or volunteer Mead, who’s been dead for more than three decades. It’s a sad index of how irrelevant the discipline seems to have become from an age when Franz Boas could make the cover of Time Magazine.

EL:Because ‘there is no neutral position,’ does all anthropology of Native America have to be activist anthropology? If so, is that requirement restricted to the anthropology of indigenous and other disenfranchised people? Are there different degrees of activism that are appropriate?

OS: I’d say all anthropology is activist in its own way, insofar as it presses for a better understanding of human experience. I find many of the calls for an activist or “public” anthropology to be a bit confining and sometimes preachy. For one thing, you can’t ever legislate in advance just what kind of anthropology will matter in the world. For all their limits and contradictions, Boas and the Boasians had a enormous role in shaping American thinking about racial equality and culture in positive directions, but they didn’t think of themselves as activists, but as scientists. If you want to get involved and write about an indigenous protest movement, that’s great. And I think the brutalization of so many indigenous groups makes it all the more imperative for anthropologists to be sensitive in their dealings with them. You’re not likely to get that necessary tribal approval for work that’s not perceived as useful in one way or another anyway. But I’m against political litmus tests for anthropology or efforts to police just what the discipline should or shouldn’t be.

EL: Do the ‘poles of debt and threat’ that you ascribe to ‘white American’ attitudes towards Indians make up a binary that can exist simultaneously? Or do the two extremes characterize different, alternating ‘eras’ of activity?

OS: I think, very generally, that we’ve swung very broadly back and forth between these two poles. Back in the mid-19th century, when the Indians still posed a military threat to white colonization, the idea of threat prevailed. The massacre at Wounded Knee and the end of armed conflict inaugurated the feeling of pity and debt that would prevail for most of the 20th century. But then the rise of the casino economy brought new feelings of threat and resentment against tribes from local homeowners, environmentalists concerned about parking lot and resort hotel sprawl, and others. If either threat or debt has seemed to predominate in particular periods, they’ve nonetheless always coexisted in the schizophrenic white thinking about Native Americans. There was admiration and a feeling of obligation to tribes from the very beginning of American history (and, as Philip Deloria points out, settlers even dressed up as Indians for the Boston Party with natives seeming to symbolize an unruly independence and freedom). And, conversely, outright racism and bigotry about Indians has never vanished and can be found in unvarnished form on many reservation border town even today. The backlash against the casinos has been strong in recent decades, and yet the tropes of debt, admiration, and empathy remain powerful all the same. So, yes, the poles of debt and threat have always coexisted in American thinking, and neither ever entirely vanishing from the zeitgeist.

EL: In your discussion of Viveiros de Castro’s work, you note that he does not refer to any of the recent political changes in that part of Brazil. How would you respond to an argument that he does in fact mention such changes in his introduction? Can this sort of ‘disclaimer’ accomplish the goal of situating indigenous people (or anyone else for that matter) in a modern, changing, setting?

OS: I don’t know the whole body of Viveiros de Castro’s work, but in the much-circulated article I discussed in my essay, I don’t see any real exploration of the specificities of political context, historical change, or the challenges of modernity. To the contrary, it uses the breathtakingly broad and essentialized category of “Amerindian thought” as if the extraordinary heterogeneity of native experience and culture in the hemisphere could be boiled down to some timeless common principles. I don’t have any objection to Viveiros de Castro’s brand of anthropology, and yet it is a strange sort of curiosity that what some scholars have taken to be the cutting edge of Amazonianist anthropology can pay no real attention to history and operate within the terms of an us/them, West/Other, native/non-native binary that I thought had been left in the dustbin of social theory back in the 1980s.

EL: Is it fair to claim that non-whites ‘are stuck’ studying their own people? Are there perhaps reasons beyond restriction of availabilities, and ‘a chosen sense of loyalty and obligation to home communities’ for which they might choose such sites of research? If there are, does this recast the idea of white anthropologists having ‘the freedom to pick whatever topic’ while non-whites have limited freedom in this regard?

OS: I don’t mean to suggest that Third World and minority anthropologists are somehow forced to study their own people. Beyond the fact of a chosen sense of loyalty and obligation to home communities, there are other factors that come into play, among them the fact that the structure of anthropology funding makes it easier for anthropologists no matter for their background to find money for studying “abroad” or communities of color than to study whiteness and the powerful. As much as we may want to see anthropologists do more “studying up” and “bringing the discipline back home” to the U.S., you can’t get an SSRC International Dissertation Research Award or a Fulbright for doing that. Just how it happens is not always easy to understand, and yet it’s striking how race and gender seem to structure so much about university life in an age where we like to imagine ourselves as so much more progressive than in the bad old days of legalized discrimination. Thus, for example, we have many women in the humanities and the “soft” social sciences, and many more men in the “hard” social sciences and the “physical” sciences.

EL: You express a discomfort with the concept of an ‘anthropology of Native North America,’ for the thing-unto-itself-ness, which the name implies. Is the ‘ethnological nomenclature’ a reason to abandon the term? Or is the boundedness that it implies a possible avenue into some productive areas of study?

OS: All nomenclature is arbitrary, of course, and yet we can’t do without it. The area studies model divides an interconnected world into discrete units for study, and yet it’s not been without value as a conceit for organizing academic inquiry , and very great insights have come out of it. And, as much as the arbitrariness of disciplinary boundaries demands crossing and has made interdisciplinarity into a favorite buzzword, there’s much to be said as for preserving the idea of fields called anthropology, history, English, and so forth, albeit recognizing that they should can or ever could somehow be sealed, self-enclosed domains. So, yes, the “anthropology of Native North America,” may be one of those arbitary yet useful conceits for organizing the manufacture of knowledge that’s worth not discarding altogether, although I’m not always sure about that.

Related Readings

O. Starn, The Passion of Tiger Woods: An Anthropologist Reports on Golf, Sex, and Race in America (Duke U. Press, Durham, 2012).

O. Starn, Ishi's Brain: In Search of America's Last "Wild" Indian (2004), W.W. Norton (Paperback release in June 2005).

O. Starn, Nightwatch: The Politics of Protest in the Andes (1999), Duke University Press.

O. Starn and M. de la Cadena, Indigenous Experience Today, Translated into Spanish as "Indigeneidadas Contemporaneas: Cultura, Politca, y Globalizacion" (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 2010) (2007), Berg.

O. Starn et al., The Peru Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Revised and Expanded Editon) (2005), Duke University Press.

O. Starn and R. Fox, Between Resistance and Revolution: Cultural Politics and Social Movements (1997), Rutgers University Press.