Im/migrant Children’s Narratives of Forced Family Separation in Schools

From the Series: The Damage Wrought: Immigration Before, Under, and After Trump

From the Series: The Damage Wrought: Immigration Before, Under, and After Trump

“Sometimes it’s hard to talk about it, because it hurts right here [pointing at her neck], but I want to talk.” Six-year-old Dulce explained how the lump on her throat grew every time she remembered the seventy-two days that she was away from her father, Juan, when they were apprehended, separated, and detained at the border in May 2018. Dulce and Juan migrated from Guatemala to the United States at the height of the current iteration of family separation by the United States, the zero tolerance policy implemented by the Trump administration in 2018. After being apprehended, Dulce was sent to a shelter in New York City and Juan stayed in Texas. Migrants’ narratives and investigative reports reveal the inhumane circumstances to which immigrant children and families are subjected in government detention facilities. Dulce, who is now in first grade, remembered the moment she was taken from her father. “I was wearing a pink shirt,” she explained while her father comforted her, saying, “It’s ok, now we are here, we are ok, we are safe now, hija.” Dulce and Juan are only two among thousands of parents and children who have suffered the traumatic consequences of forced separation by the U.S. government under the Trump administration.

Immigration status, conferred by federal immigration law, is a central, but often invisible, fact in children’s homes as well as in their classrooms (Oliveira 2018). As schools in the United States welcome immigrant children, students bring their experiences with family separation and detention into the classroom. Throughout my three-year ethnographic fieldwork in schools in the northeast of the United States many teachers discussed feeling uneasy engaging with children’s traumatic experiences. Teachers described a fear of “opening Pandora’s box” and not having adequate training to engage with children regarding what they called “not classroom issues.” Children in those classrooms, however, worked to articulate the impact of punitive immigration policies in their lives. Their histories of emotional and spatial dispossessions were an ongoing and critical part of their everyday experiences in classrooms. But were the adults in the classroom listening?

Young children’s recounting of border crossings and state violence are not always welcomed inside classrooms. Sarah Gallo and Holly Link (2015, 361) describe these topics as politicized funds of knowledge: “the real-world experiences, knowledges, and skills that young people deploy and develop across contexts of learning that are often positioned as taboo or unsafe to incorporate into classroom learning.” According to the authors, citizenship, legality, imprisonment, and separation are among the experiences that are kept out of the classroom because some teachers and school administrators may consider them to be complex issues that have no place in school. Still, migrant children find ways to share their thoughts and experiences either with classmates or through drawings and other modes of expression when teachers actively avoid listening.

Julie, a Brazilian six-year-old, described her border crossing experience while she was reading a non-fiction science book about the desert in her first-grade classroom. Sitting at a round table, Julie closed the book, looked up, and said, “tinha um homem daqueles de filme com revólver e cachorro . . . colocaram minha mãe de um lado e eu do outro e depois de dois dias a gente tava junto . . . eu chorei sabia? Porque eu pensei que tinha perdido minha mãe e minha casa” (there was a man like from the movies with a revolver and a dog . . . they put my mom on one side and I on the other side and after two days we were back together . . . I cried, you know? Because I thought I had lost my mom and my home). Julie’s unprompted connection between her classroom’s formal curriculum and her own personal trajectory was not incorporated, discussed, or even acknowledged by her teachers or the school staff. Instead, Julie and her peers were the ones processing the stories of crossing the border together. We must center children’s experiences in classrooms to make space for healing and learning to happen.

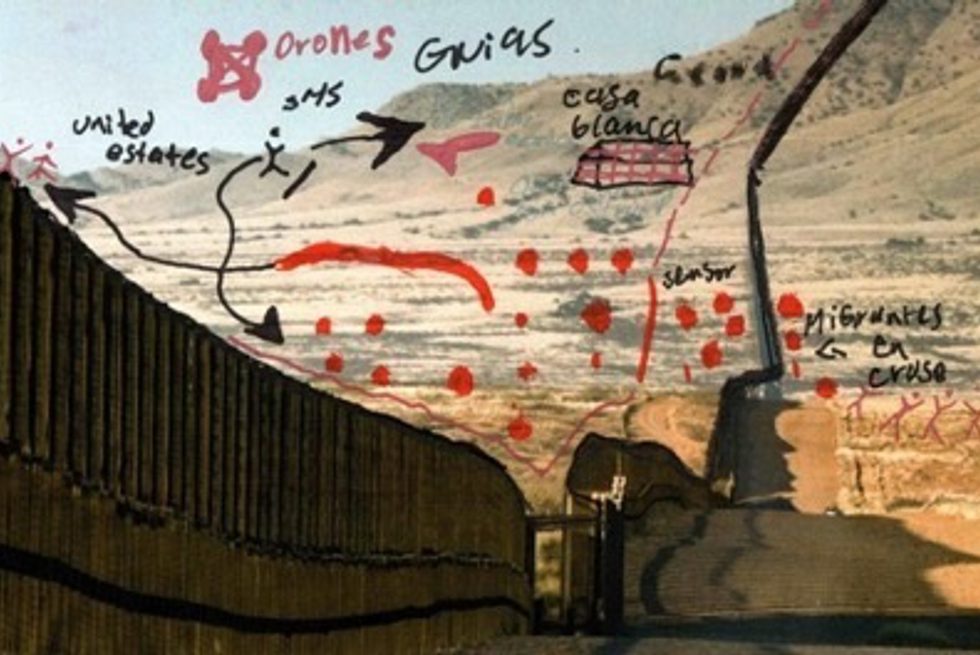

As part of my ethnographic fieldwork in two elementary schools in the northeast of the United States for three years, I asked children to draw what represented for them their home countries as well as their newfound home: the United States. The drawing below by Carlos, six, was a response to the prompt, “Draw what you think about when you think of the United States.” Carlos was detained with his parents for four days before being placed in a religious-based shelter in the United States for three weeks with his family. The image below is Carlos’s depiction of the police officer that, according to him, told them to get in line to get soap and a toothbrush at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Carlos drew the picture as he was sitting inside his first-grade classroom. Beatriz, a seven-year-old Brazilian immigrant student, contributed, “Semana passada mesmo eu escutei a história de gente que fica presa” (Only last week I heard the story of people who were arrested). A third child, Liam, also from Brazil, chimed in, “meu pai sempre fala com advogados porque a gente quer poder viajar para o Brasil, sabe?” (My dad always talks to lawyers because we want to be able to travel to Brazil, you know?). A fourth child, Ana, whose dad was from Guatemala, jumped in, “Did your dad also wear the machine on the leg [ankle monitor]?” The classroom teacher noticed a chatter at the small round table and addressed the children, “What are we doing here? Are we learning here?” All of a sudden there was silence around the table.

As children grapple with the experiences of border crossing as well as confront the challenges of living in a new country during a global pandemic, we need to listen closely to their stories as a means of affirming their struggles, fostering a sense of community belonging, and developing new ways to support a young population who have endured horrific harms. The damages from the Trump administration’s zero tolerance policy are spectacularly on display in detention camps along the border, but schools also give us a glimpse into the long-term public impacts that brutal and racist policies can have on our youngest students.

Gallo, Sarah, and Holly Link. 2015. “‘Diles la verdad’: Deportation Policies, Politicized Funds of Knowledge, and Schooling in Middle Childhood.” Harvard Educational Review 85, no. 3: 357–82.

Oliveira, Gabrielle. 2018. Motherhood across Borders: Immigrants and Their Children in Mexico and in New York. New York: NYU Press.