In Between Silence

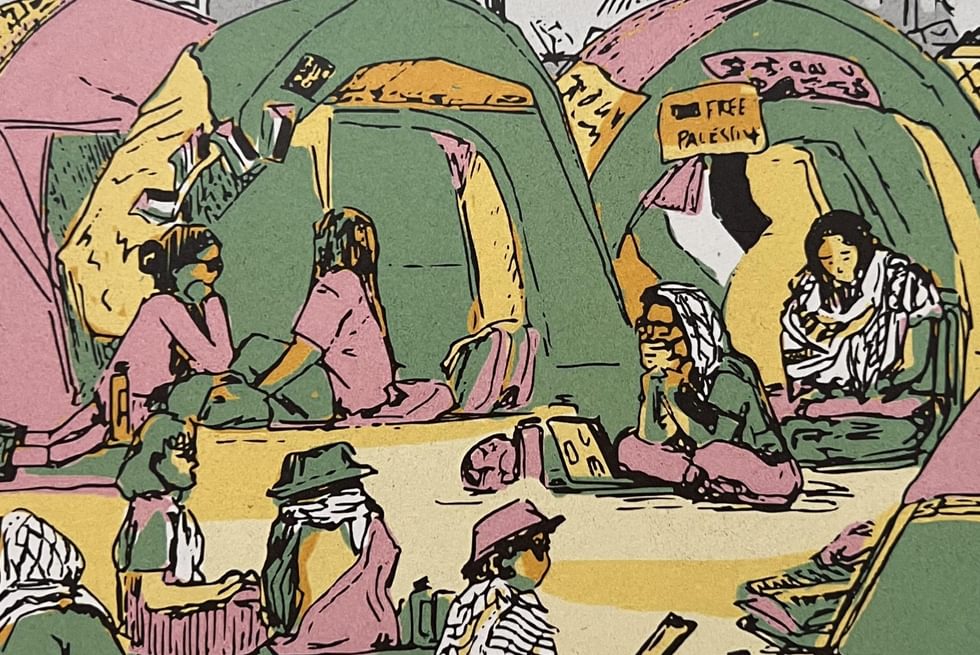

From the Series: Counter Archives: Fieldnotes from the Encampments

From the Series: Counter Archives: Fieldnotes from the Encampments

I have tried to start this essay half a dozen different ways, and each time it seemed like a futile effort. In response to the invitation to contribute, I proposed something ethnographic that would attempt “to situate what happened at Wesleyan University from October 2023 to May 2024 within the context of broader ethnographic and anthropological literature on social ties forged during moments of ‘crisis,’ in-betweenness, and waiting.” That was at least what I submitted and which the editors graciously agreed to include here. I’ve written that piece, or something like it, but this is not it.

I would very much like to write about the particular types of being-in-common that emerged in the particular spatio-temporal confluence of over 100 tents spread across our campus lawn for 3 weeks, as students, staff, faculty, and community members found themselves outside of the normal structures of the university and within a time and space demanding a way of being-in-common differently. To write about how these forms of commoning, communing, and community changed the social fabric of our campus after the strict rules governing social life during the COVID-19 pandemic. I would like to talk ethnographically about how time was lived over these three weeks and the communal sentiments formed were far and beyond what anthropologists would normally associate with liminality. About how it could push us to consider how what seems like passive time spent waiting (in an encampment, for a response from the university, or steadfastly in a tent, for the end of hell on earth, for the right to return), is not parenthetical time but rather a paradigm for life lived within violently enforced temporal enclosures. But truth be told, I don’t know that I can. To do so runs the risk of comparing what happened on our campus to what is happening in the Gaza Strip, and in other ways in all of Palestine, and I think even mentioning those words veers too far into that domain.

I will still attempt to “situate” these events, alongside the ongoing horrors and assaults on Palestinian life, but I am not sure of what use it is. Every time I have started to write this, the same series of doubts come cascading along. What’s the point? Who am I to write this? Should I write it from my perspective as a Palestinian-American? As an American citizen and taxpayer whose tax dollars are funding Israel as it rains hellfire on the Gaza Strip and now Lebanon? And, shamefully, should I do so anonymously to protect my career? I’m an early career assistant professor, shouldn’t I wait for tenure before writing about this? How will this publication, the one you’re reading now, impact my chances at visiting friends, family, and crumbling houses in Ramallah the next time I try to cross the Israeli checkpoint at Allenby Terminal/King Hussein Bridge from Jordan to Jericho? Will they run a search on my name during the inevitable detention and find this piece? Is it cowardly to think like this, in face of what we are—I am—witnessing from the comfort of the West? I don’t think I am alone in having these feelings among the junior faculty I know, Palestinian or otherwise.

In 2016, because of a frustratingly common scenario, perhaps familiar to others who have also waited for hours in detention there, I was rejected at King Hussein and ended up at the northern Sheikh Hussein crossing. Before she told me to step aside for “extra security screening,” the Israeli border official asked me about “my occupation.” I’m working on a PhD in anthropology, I replied, focusing on questions around borders, migration, and time spent waiting in northern Morocco. Not being able to help myself—it was nearly 11 PM at this point and I had been trying to cross since around 11 AM—I asked her about “her occupation.” I’m working here part-time, but I’m studying anthropology too, she excitedly told me, for my undergraduate degree.

I don’t know why I’m sharing this. It seems like a funny story, but nothing about this is funny, not at all. Perhaps I’m thinking with Palestinian novelist Emile Habiby’s satire The Secret Life of Saeed: The Pessoptimist (1985) about the need for a healthy sense of irony in the face of a never-ending wait for something better. At least she had likely heard of sound-blindness?

This is the issue I keep having. I want to talk about what happened at Wesleyan, what’s happening at Wesleyan still, but how can I talk about that, without this? During the student encampment on Wesleyan’s campus from April 27 to May 18, 2024, conversations about how to center the protest movement on Palestine and not overly focus on campus events slowly grew amongst students and faculty. While there was an understandable desire to talk about these events, and tensions between different groups with ties to the campus, everyone needed a reminder at times that this was about what was happening there, in Palestine, as much as it was here, in Middletown, Connecticut. That’s the tension at the center of this short reflection, which is supposed to be about here (the imperial core), not there (its colonial outposts).

With that in mind, what can we do as we return to students and colleagues who—at least on our campus—wonder what will come as committees promised by the university look into the student Palestine Solidarity Encampment demands? It feels impossible to look upon any of this with optimism, but perhaps we can instead think a bit “pessoptimistically” about where we have been, how we got here, and where we might be going. At least the university did not call the police on the students, and we have committees? Never mind, the new semester began with police detaining students during a sit-in, new security cameras with facial-recognition capabilities in the center of campus, and a wholesale rejection of the Committee for Investor Responsibility’s proposal for divestment.

All last fall I heard, repeatedly, “oh well, what we can do?” Our students clearly don’t feel that way. Although Wesleyan offers few courses on the question of Palestine within our small “Middle Eastern Studies” minor, as our students mobilized alongside global student and youth movements in support of Palestinian life even before the encampments began, they also began to develop their own educational curriculum. As students of all backgrounds began to reference the genocide in Gaza in class, it became clear that while many of us, as a faculty, whispered behind closed doors about how and if to do so, we ultimately felt ill-equipped or even uncomfortable talking about Palestine and Israel pedagogically in our classrooms. The structure of small institutions like Wesleyan means that we do not generally have much regional overlap among faculty. What results can at times feel at times like intellectual isolation accompanied by demands from others on campus to proffer expertise and solutions. We can’t begin to properly do that without meaningful institutional support. That does not mean, however, that we cannot engage in the study and teaching of Palestine.

Several colleagues and I attended the students’ first gathering in response to increasing bombs raining down on Gaza in the weeks after October 7, a mourning for those killed before, on, and after that day. Among us, the question kept coming up; amidst the flood of faculty emails about daily events happening on campus—business as usual I guess—and the odd question about recommendation for heat-pump vendors, why wasn’t anyone saying anything? The silence was intolerable. I don’t know if it was out of anger, grief, fear, or the feeling of utter isolation in the face of this silence, but some of us eventually came together as the “Faculty Ad-Hoc Network on Palestine.” Throughout the fall and spring semesters we organized events, readings, seminars on Palestine and Israel and, slowly, began to organize around a curriculum on Palestine Studies and Wesleyan appointed a few of us to explore formally what such a course of study might look like. As the student encampments began to emerge, though, it became clear that our ad-hoc network needed to think about how to support our students in their organizing too, even when we couldn’t meet their desires for perfect avatars of solidarity.

Palestinian politics, as with any other sort of politics, are complex. I am not referring to oft recited dismissal of the Middle East as “too complicated” or “too sectarian” to understand. Instead, I mean simply that the politics of a colonized polity living under siege are inevitably complicated. All of this is to say—and again my apologies, because how can we talk about this without talking about that—it is neither easy for students to find complete political alignment with one another nor simple for faculty to coalesce around a singular political agenda. And so, cautiously and with some fractures along the way, a chapter of the Faculty for Justice in Palestine formed alongside our Ad-Hoc Network on Palestine. Those involved in both found a clear separation in their mandates, the former as an advocacy chapter, and the latter focusing on pedagogy.

Time will tell if either or both survive. Both include senior and junior colleagues, and no one quite knows who belongs to what. That’s the operating condition when so many of us are afraid to sign our name to this work and anger the wrong person without knowing who that person might be. It is uncomfortable, embarrassing, and frustrating to admit this. At the end of these fractured fits and starts of an essay, it seems clear that there is indeed much many of us feel we can’t do, given our structural positions. But, what can we do? Then again, given these same elite structural positions in the institutions of the Global North, quite a bit, if we are willing to think a bit differently about the mandates of our own occupations. The project of collective liberation demands no less.