In the Meantime

From the Series: Book Forum: A Possible Anthropology

From the Series: Book Forum: A Possible Anthropology

Anand Pandian's A Possible Anthropology (Duke University Press, 2019) situates the discipline as a transformative mode of inquiry. An encounter. A response to “dark times” and crisis. Pandian demonstrates that anthropology’s unbounded interest in the human, the question of being human, and humanity itself, has the tools to answer the “what’s next?” that we might be thinking about during this current period of time.

One thing that was particularly striking in this book was the reminder of anthropology’s ability to ground us in concrete reflections of everyday life and emergent collectivities. On the question of what is yet to come and ethnography’s political and moral intentions for the world, Pandian suggests seeing “humanity as a moral feeling of responsiveness” (107). This dovetails with Deborah Thomas’s (2019) form of witnessing, or what she calls Witnessing 2.0. A form of seeing and bearing witness to life that is co-performed. One that is committed to a moral praxis. A witnessing that has responsibility to ourselves, our politics, the communities we work with, and that of humanity. A witnessing that is “response-able,” which requires us to note and act upon visions of solidarity, empathy, and political action (Thomas 2019, 3). Not only that, but this form of witnessing evokes the recognition of being human—a feat clearly emphasized in Pandian’s quest for demonstrating the openness and possibilities that exist when we pursue the question of “being.” An ethnographic encounter, indeed.

The book is an invitation to make space and be in dialogue with other anthropologists, writers, and artists. I think of the women and youth I work with who are engaging in their own modes of story-telling, reflecting on undocumented life with the same care as an anthropologist. Pandian's chapter 3, "Politics, Art, Fiction, Ethnography," clearly demonstrates that people in the world are doing the work of anthropology through their curiosity, narratives, concerns, hopes, and dreams on humanity and its futures. The book asks, “why do anthropology?” Sometimes I find myself sitting with the same question. What does anthropology have to offer me when I could take the tools provided by the discipline, go home, and work with undocumented migrants instead? A Possible Anthropology reminded me of Audre Lorde’s “School Note,” “There is no place that cannot be home nor is,” (2000, 127). There is also something to be said about trying to make anthropology home and the academy habitable, which Pandian’s introduction also grapples with.

The narratives in A Possible Anthropology remind us of the question of doing anthropology. We don’t do anthropology because we’re merely curious about social life and institutional practices. We also do it for the experience in the encounter, in witnessing how people narrate their stories and make them legible for both themselves and the anthropologists. We do it for the openness and the moral practices that guide our political work. The book is a meditation on reflexivity, fieldwork, and the possibility and futures of anthropology itself.

The stories we return with from the field have a life of their own. It allows us sympathy, a possibility of collaboration, and I don’t just mean the handwave or stamp of “activist” and “engaged” anthropology on paper, but the real work of grappling with the tensions that exist both in fieldwork and in our academic homes. During my fieldwork this past summer, one of the women I worked with reflected on sharing her migration narrative at community events. Undocumented migrants are usually encouraged by nonprofits to share their migration stories to boost the community’s moral, to educate potential comrades/allies, and for doing the heavy work of shifting the representation of what an undocumented migrant is. She comments on how I shared my narrative, leading both of us to a discussion about the stories we tell ourselves.

Lucía says:

Like, listening to your story yesterday . . . I mean . . . I cried, you know? It was just—the way you said it reminded me a lot of how I’ve kind of shifted to tell my story. I kind of saw what you did. And I think a lot of us done that: focusing on main specific points that reveal the peak—the pain, you know? I talk about those patterns and I don’t think I can really translate the significance of what that means to me, you know?

This is a long conversation Lucía and I have been having for nearly five years. A return to our stories, a question about representation, and what it means to recognize yourself as a human being even when the state insists on your illegality and deportability. How do I translate the story she is already struggling with? Fieldwork doesn’t leave. It follows. At least for me, being part of this community, sharing these formative experiences with Lucía. There isn’t an after. There’s no continuation. It always is. This open-endedness asks Lucía and I to work through the experience of being storytellers.

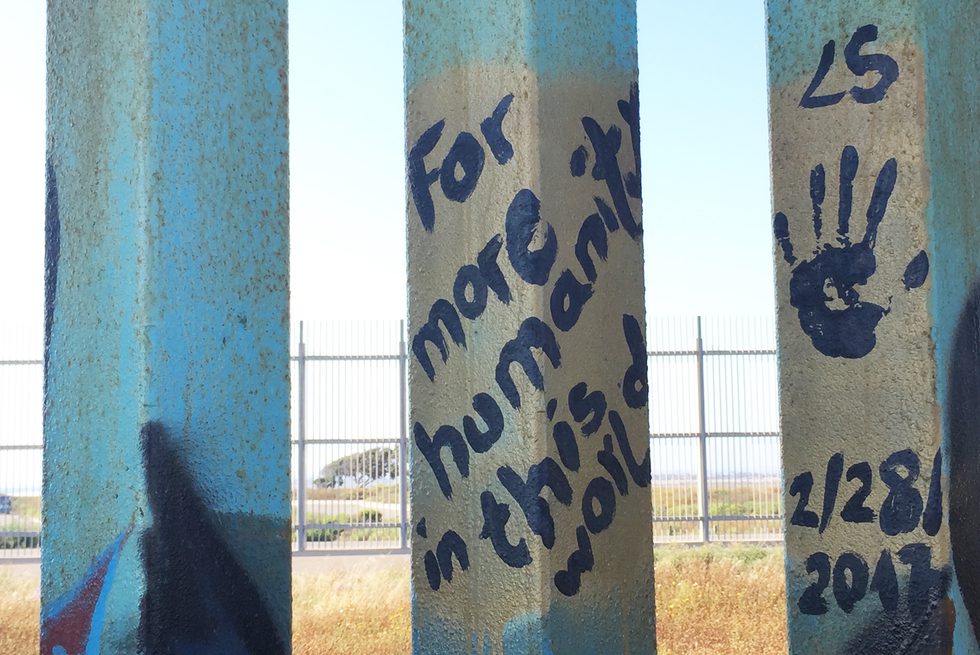

Here, I take her narrative and share it with you. It’s one fraught with frustration, uncertainty, but always looking at the horizon. Whatever it maybe be. And not in the naïve sense that buys into the promise of liberal citizenship, but the notion of life elsewhere. Outside these borders. Lucía had mentioned self-deportation as this possibility. Leaving the United States to seek life elsewhere because she knows that she exists beyond illegality and that possibilities exist elsewhere. When she tells me this, she is refusing her current situation (Simpson 2017; McGranahan 2018). This refusal allows her the possibility of imagining a different world, which is one of my key take away points from Pandian’s book.

I end with a question as a parting reflection:

If anthropology has the tools of response, responsibility, and looking at the horizon requires the imagining of a future—a humanity yet to come, what do we do in the meantime as we struggle for equal footing, for recognition and legibility as also human? What does this “a humanity yet to come” look like during a state of urgency, where one cannot wait for the horizon, and when the hope, the imagining of a future isn’t enough?

Lorde, Audre. 2000. The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde. New York, N.Y.: W.W. Northon.

McGranahan, Carole. 2018. "Refusal as Political Practice: Citizenship, Sovereignty, and Tibetan Refugee Status." American Ethnologist 45, no. 3: 367–79.

Simpson, Audra. 2007. "On Ethnographic Refusal: Indigeneity, ‘Voice’ and Colonial Citizenship." Junctures: The Journal for Thematic Dialogue, 9: 67-80.

Thomas, Deborah A. 2019. Political Life in the Wake of the Plantation: Sovereignty, Witnessing, Repair. Durham, N.C.: Duke University PRess.