Introduction: A Possible Anthropology Forum

From the Series: Book Forum: A Possible Anthropology

From the Series: Book Forum: A Possible Anthropology

These are no doubt times of unease. The days before us feel both eternal and fleeting. They call for a re-examination of what it is that we are doing with anthropology. How might we respond to planetary crises, create alternative horizons of possibility, and address the rampant inequalities and vulnerabilities that exist in anthropology and beyond. In A Possible Anthropology (Duke University Press, 2019), Anand Pandian ventures into the depths of the discipline, as well as into some of the domains from which we do anthropology: reading, writing, teaching, and fieldwork.

Pandian is a collector of lessons who montages historical offerings within anthropology with other kinds of worldly encounters including art, fiction, and activism. Methodological dispositions, the illuminations brought forth from certain images, and the world-stretching depth found in reverie and speculation all make up the repertoire for what certain anthropological sensibilities have to offer. Through these constellations, Pandian demonstrates what anthropology has known all along: the transformative potential that comes with allowing oneself to becoming entranced by the swirling flow of lived experience and chance.

As examples of such lessons, we could perhaps include Jeanne Favret-Saada’s (1980) call to be caught by the witches’ power, Michael Taussig’s (1993) approximation to the unknown through the relays and jolts brought about by our mimetic relation to the world, or Natasha Myers’s (2017) call to decolonize and vegetalize our sensorium and come to imagine the world as our trees and our other earthly kin do. Somewhere between the “deeply empirical and highly speculative” (6), anthropology can offer new pathways towards a livable planet; towards a humanity yet to come. Such is the approach Pandian makes an invitation for, one in search for revelatory angles of contact where practice and experiment become world-changing in perspective. The sprouting of dialectical images leaves us with new offerings. Pandian shows, through the writings of Zora Neale Hurston, Bronislaw Malinowski, and others, how anthropology bears the potential to tap into the “occult powers of metamorphosis . . . in the form of vivid stories, images, and sounds” (7). Pandian adds:

An ethnography is magical by nature, founded on the power of words to arrest and remake, to reach across daunting gulfs of physical and mental being, to rob the proud of their surety and amplify voices otherwise inaudible. (7)

If, as Pandian asserts, one of anthropology’s greatest potentials comes in the form of stories, images, and sounds, if it is these metamorphic and arresting forces that could make us otherwise, how might the discipline begin to take more seriously multi-modal efforts and genres in anthropology, which thus far have been valued as “supplemental” or “experimental” in relation to the perceived superior rigor of academic writing? Could our work in multi-modal form allow us to reach broader audiences? Might not this experimentality with form—which has been part of the discipline since its incipient stages—allow us to expand and open anthropology to a wide array of genres at our disposal? Could we incentivize such seriously playful experiments in ways that may transform us in the process by institutionalizing multi-modality in anthropology and granting it the same merit as research article publications? Such questions may reach a new level of priority in times of crises, virtual learning, and physical distancing—as we strive for other forms of being-with, making impacts, and imagining what anthropology can be.

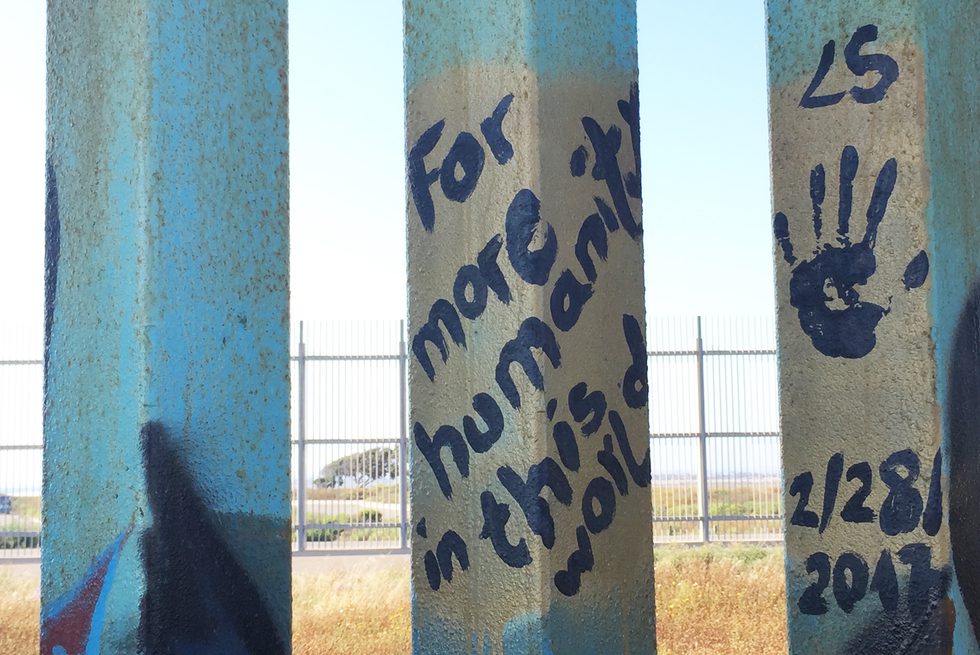

A Possible Anthropology also tackles one of the most troubling categories in anthropology and the humanities more broadly: the human. Has “humanity” been abandoned too quickly by those who are calling toward a beyond the human (11)? Pandian decides to sit with the troubles of “the human,” by taking up this figure not so much as constituted by some a priori ontological grounds or pre-defined fixed “essences” (see also Geroulanos 2010), but as a certain kind materiality (and spirit) to till with, to cultivate a political and moral horizon to come (11). Much like anthropology’s own troubled and “ambiguous heritages” (4), the figure of the human is also fraught with colonial and racialized roots. Could the cultivation of this humanity to come, premised on anthropology’s method of experience and existential generosity, be a path toward doing away with a human whose historically specific foundation was based on the production of difference and exclusion? Moreover, could cultivating any kind of humanity be possible without its outside, without negation? In Julietta Singh’s (2018, 139) Unthinking Mastery, we are reminded that:

by claiming the human—over and over again, across discrete historical moments and within particular political contexts—we have in this act of bringing some into the fold of humanity continued to produce others as abjectly outside.

And yet is precisely those who have been relegated to the outside of the human and to its margins that may not have the option to as easily discard this category despite all of its troubles. So how might we then move forward from the impossibilities that saturate the category of the human? A Possible Anthropology is bold, caring, and creative in trying to confront these issues head on, in trying to imagine some other kind of world.

This book forum invites a group of anthropologists to reckon with Pandian’s contribution, and to reflect on pressing concerns in the discipline.

The essays on this forum including this introduction were written sometime between December 2019 and February 2020. Though these essays were completed prior to the emergence of the Covid-19 outbreak as a full-blown pandemic, some of these reflections still carry the urgency of planetary crises and the critical need to consider a wide array of issues in anthropology and academia.

Favret-Saada, Jeanne. 1980. Deadly Words: Witchcraft in the Bocage. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Geroulanos, Stefanos. 2010. An Atheism that Is Not Humanist Emerges in French Thought. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Myers, Natasha. 2017. “Ungrid-able Ecologies: Decolonizing the Ecological Sensorium in a 10,000 year-old NaturalCultural Happening.” Catalyst 3, no. 2: 1–24.

Singh, Julietta. 2018. Unthinking Mastery : Dehumanism and Decolonial Entanglements. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Taussig, Michael. 1993. Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses. New York, N.Y.: Routledge.