This post builds on the research article “Blessed Acts of Oblivion: On the Ethics of Forgetting” which was published in the February 2025 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

In this interview, Paolo Heywood further discusses the uneasy art of forgetting in Predappio, a town still bound to Mussolini’s shadow despite its attempts to appear ordinary. Forgetfulness is never simple; as long as damnatio memoriae lingers, so too does the restless need to forget. It is like a child playing an ordinary game in the forest—if only one could forget what happened nearby.

Yichi Zhang [YZ]: Could we begin by exploring your own remembrance—and forgetfulness—of Predappio. Given your personal connections to the town, what stands out in your recollections, and what fades away before and after your fieldwork? How did these dynamics shape your decision to choose Predappio as a site for collecting memories as an anthropologist?

Paolo Heywood [PH]: Thanks, that’s a really sharp opening question. My family are from the nearest town to Predappio, and they also have a house in the Apennines further up the road that runs through Predappio to Tuscany, so I have very strong childhood memories of sitting in the back seat of my uncle’s car and looking out the window as we drove through it. I can remember amazement at how different Predappio was to all the other picture-postcard Tuscan villages nearby, and I can also remember astonishment, when I was old enough to understand, that what I was looking at was basically a giant memorial to the original Fascist dictator.

That status is what I went there to study in 2016, as part of a wider European Research Council (ERC)-funded project on free speech at Cambridge (our book, Freedoms of Speech (2025), on that has also just come out). I guess the obvious thing to say though about what gets so easily forgotten in those early memories of mine and also in wider popular perceptions of Predappio is that it’s also a home for the people who inhabit it—it’s not actually (or at least not entirely) the ‘Disneyland of the Duce,’ as some people call it, it’s also a place where ordinary people try and live ordinary lives. So what I ended up trying to do in this piece (and in my book, Burying Mussolini (2025)) was to think about how people live ‘with’ Fascism, not just as history—Fascism has never been just history in Predappio—but as it is materialized and embodied in so many aspects of life in the town. Forgetting, or at least trying to forget, their relationship to Fascism and Mussolini is for many people a part of that endeavour of living an ordinary life.

YZ: I really appreciate your argument that ‘to forget’ is not merely an honest mistake or a moral failure but can function as an ‘ethical technology.’ Toward the end of the article, you briefly mention oblivion in relation to the Soviet Union, which made me think about other contexts where people ‘forget’ so-called incorrect memories—not always because they have little choice (as in modern China, for example).

Turning to a perhaps more unsettling aspect of this, then, is forgetfulness in Predappio always carefully constructed and sustained? Are there moments when such effort falters—when old memories resurface unexpectedly, not just in confrontation with ‘the other’ (such as neo-Fascist visitors) but in moments facing oneself and one’s own pasts and futures. What happens in those instances? Could this sometimes lead to a kind of schismogenesis, or at the very least, a struggle for selfhood that extends beyond expected discontinuities of the self—in Predappio, or in Italy more broadly?

PH: That’s another great question, and yes certainly, I definitely don’t think that forgetting is always a seamless or complete process. Some people are very self-conscious about it as a process too—they’ll talk about ‘damnatio memoriae,’ often with reference to the attitudes they think others hold about them and their home, but also sometimes just as a kind of flat description of something that’s happened to a chunk of their history and something they’ve played a part in.

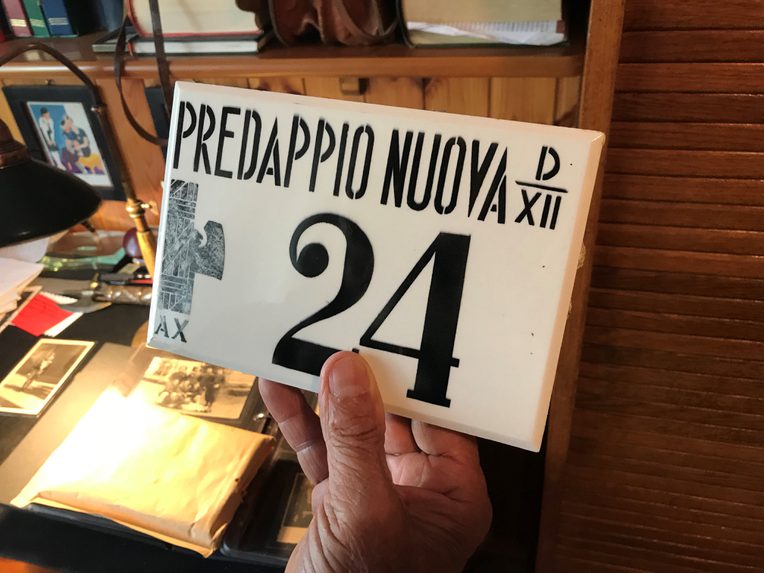

In some cases, people actually did the kind of thing a sentence of damnatio memoriae was supposed to have brought about in Ancient Rome, as I understand it, like chiselling off the street signs that had fascist symbols on them in 1943, as soon as Mussolini had been deposed. And they weren’t doing it because anyone told them to do it, but I think partly, at least, out of some sense that reminders like that would cause precisely the kind of ‘unexpected resurfacing’ you describe. One exemplary story I heard was of a young teenager in 1943, encountering the father of one of his friends chiselling off the sign on the street outside his house. The teenager stops and stares, and his friend’s father asks him what he thinks he’s looking at, and if he’s a balilla (which was what the Fascist youth organisation was called). The teenager points out that the man’s own son had been a balilla with him until only recently, at which point the man comes down from his ladder and starts beating the teenager up. I guess that’s a response to the sort of thing you might mean by a ‘struggle for selfhood’—a reaction to being forced to face one’s own (in this case very recent) past whilst literally in the act of trying to efface it.

As you suggest, this sort of thing would also often happen more straightforwardly in relation to neo-Fascist visitors, particularly in light of their assumptions about how local people feel about their most famous son. Visitors often assume that people in Predappio agree with their views, and try and engage them, in ways that even those on the right of the political spectrum usually don’t approve of. And, of course, then there are also questions from outsiders like me…so I think forgetting is definitely a practice rather than an achievement.

YZ: I also wonder—at heart (if you’ll allow the expression)—what ultimately propels people to remember and forget? Avoiding discomfort is one reason, but what does ‘uncomfortable’ actually feel like? Could you offer some further analytical insight into the affective dimensions of that experience as it emerged in your ethnography?

PH: That one’s actually quite a tough question in a way, and there’s a reason that I tend not to make too much use of what in other contexts is obviously a productive analytical language like that of ‘dissonant’ or ‘uncomfortable’ heritage. Yes, there’s definitely a sense in which Predappio is a perfect example of that kind of heritage, and I knew elderly people who would speak of literal pain, not in their hearts but in old war wounds, when confronted by things they’d rather forget. But for the most part, and unlike, say, the German case that Sharon Macdonald has described so brilliantly, the ‘discomfort’ in question, if that’s still the right word, is often only implicit—manifested by the kind absence of attention or connection that forgetting exemplifies, rather than by a negative or reactive attention.

As I point out briefly in the article, it’s important to note that ‘memory’ in Predappio is quite often invoked by precisely the people that most locals want to distance themselves from: the neo-Fascists who come to visit. They are referred to most commonly as ‘nostalgics’—so their desire to remember, or inability to let go of the past, is exactly what’s thought to mark them out. If you feel ‘discomfort’ about the past, then you clearly haven’t forgotten it. So, whilst I think there definitely is of course an affective dimension to people’s relationship to their heritage, the point of forgetting is in some ways is to cut this connection altogether.

To go back to the contrast with the German case, I often think of this great description Macdonald gives of the self-conscious strategy of ‘banalisation’ or ‘profanation’ the local administration in Nuremberg adopted towards the Nazi rally grounds. The strategy entailed ‘doing ordinary things that did not “give recognition” to there being anything special about the site’ (2012, 88). This could be an almost perfect description of people’s attitudes in Predappio, except that this attitude is never articulated as a ‘strategy,’ because to do so would precisely be to ‘give recognition’ to what the attitude is supposed to ignore/forget.

Rather than a strategy then, or a completely conscious register of feeling, I suppose I would think of forgetting and the ‘discomfort’ behind it as more of a set of embodied practices, which people know they’re enacting but which are also somewhat second nature.

YZ: This leads to a theme I know is central to your book Burying Mussolini (2025): the ‘everyday’ and the ‘ordinary.’ Could you elaborate on the relationship between ethical technologies of forgetfulness and the experience of ordinariness? How does this process prevent the ‘ordinary,’ if that is the case, from becoming something closer to a feeling of nothingness or emptiness?

PH: That’s a great way to frame the relationship between this paper and the wider argument of the book actually, because my point in the book is that people in Predappio—and in other contexts too I think—work hard to cultivate a sense of ordinariness (where in anthropology we often take ‘the ordinary’ for granted). Like most senses of ‘ordinariness,’ this one is both relational and substantive, in that it derives its meaning from opposition to the ‘extraordinary’ debates about Fascism, history, and memory within which most people situate Predappio, but also from a set of qualities that are seen to inhere in what it means to be ordinary. I’ve made this argument in a piece for Comparative Studies in Society and History in regard to particular exemplary figures in local narratives—such figures exemplify ordinariness both by their distance from Predappio’s ‘extraordinary’ heritage, but also by possessing virtues people take to embody ordinariness, like modesty, pragmatism, and humility (Heywood 2022).

In the case of forgetting I think things often work in similar fashion, as an ethical technology comparable to that of exemplarity. If you take the story in the article of Giorgio’s narratives of boyhood games in the grounds of the Rocca delle Caminate, for instance, you can really see that dynamic at work: memories so ‘ordinary’ as to be banal are in fact striking to an observer in this context because of what one might think people ‘should’ remember about the place.

Playing games in a forest as a child has a substantive sense of ordinariness about it, but it also has a relational sense because to remember such things is precisely not to remember—to forget—the fact that the forest might otherwise be populated by the ghosts of dead partisans, murdered in the castle it surrounds.

So there’s nothing ‘empty’ about the ordinariness in question, even though it is, as I’ve said, to some extent relational. Remembering things like this in place of others is I think a way of giving shape and substance to the sense of ordinary life people are after.

What makes this sense of ordinariness interesting in Predappio, too, I think is that this constructed ordinariness serves a specific ethical purpose—it allows people to claim a right to a life not overdetermined by historical association. When people say that they're ‘just like any other town,’ they're not denying reality so much as asserting a moral claim to be judged on their own terms rather than through the lens of Mussolini's legacy.

YZ: Finally, I’d like to ask about change in the rhythms of political memory. As contemporary politics continue to unravel and generations pass, what happens to the traces left behind? Do old memories settle in forgotten corners, or do they find new voices, reshaped by those who inherit them? Is there a danger that forgetting will turn into erasure, or does it work more like sedimentation, layering the past in ways that may one day be unearthed again?

PH: Again, I don’t think there’s any risk of forgetting turning into erasure when it comes to what makes Predappio famous whilst hundreds of thousands of people keep coming there demanding that Italians ‘remember’ all the good that they think Mussolini brought to the country. That’s obviously in spite of the fact that most of the people who come have no such ‘memories’ themselves, having been born long after the fall of Fascism. Similarly, there are no shortage of people for whom Predappio remains emblematic of all the reasons Fascism’s crimes need remembering.

I think your metaphor of sedimentation captures something important about how these processes work overtime. Political memories in Predappio are definitely layered rather than erased, with different strata becoming more or less visible depending on the political climate. The election of Giorgia Meloni and her post-fascist Brothers of Italy party has certainly brought certain previously submerged layers closer to the surface, as neo-Fascist visitors make clear when they talk about their newfound ‘freedom’ to remember.

At the same time, and partly for exactly this sort of reason, I think it’s not just particular memories that are subject to inheritance or erasure but also the techniques of dealing with them that we’ve been talking about. So young people in Predappio obviously haven’t forgotten the heritage of their home—how could they, or anyone who lives there—but, alongside the historical facts, they also learn ways of dealing them, like the ones I try and describe here and in the book. And I doubt these techniques will be erased while the memories themselves remain contentious—young people may not remember the post-war conflicts over memory like some of those I describe in the article, but they don’t need to while metaphorical descendants of both Fascists and antifascists continue to treat the town as a battleground. So the motivation for the techniques themselves is still very much alive: people still remember how to forget.

References

Candea, Matei, Taras Fedirko, Paolo Heywood, and Fiona Wright, eds. 2025. Freedoms of Speech: Anthropological Perspectives on Language, Ethics, and Power. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Heywood, Paolo. 2022. “Ordinary Exemplars: Cultivating 'the Everyday' in the Birthplace of Fascism.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 64, no. 1: 91–121.

———. 2025. Burying Mussolini: Ordinary Life in the Shadows of Fascism. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.