This post builds on the research article “Kinky Empiricism,” which was published in the August 2012 issue of the Society’s peer-reviewed journal, Cultural Anthropology.

Editors' Footnotes

Cultural Anthropology has published numerous articles on ethics and reflexivity in anthropological research including George Marcus's "The End(s) of Ethnography: Social/Cultural Anthropology's Signature Form of Producing Knowledge in Transition" (2008), Michael Fischer's "Anthropology as Cultural Critique: Inserts for the 1990s Cultural Studies of Science, Visual-Virtual Realities, and Post-Trauma Polities"(1991) and "Culture and Cultural Analysis as Experimental Systems" (2007), Charles Hale's "Activist Research v. Cultural Critique: Indigenous Land Rights and the Contradictions of Politically Engaged Anthropology" (2006), Quetzil E. Castañeda's "Ethnography in the Forest: An Analysis of Ethics in the Morals of Anthropology" (2006), and Allen Chun's "From Text to Context: How Anthropology Makes Its Subject" (2001). Cultural Anthropology has also published articles on affective politics of history and text in (post)colonial contexts. See for example, William Cunningham Bissell's Engaging Colonial Nostalgia (2005), Liam Buckley's "Objects of Love and Decay: Colonial Photographs in a Postcolonial Archive" (2005), Mark Busse's "Wandering Hero Stories in the Southern Lowlands of New Guinea: Culture Areas, Comparison, and History" (2005), and Nils Bubandt's "From the Enemy's Point of View: Violence, Empathy, and the Ethnography of Fakes"(2009), the latter two of which also focus on New Guinea.

Interview with Danilyn Rutherford

What was the context in which this paper came out?

This paper, together with the various papers that are in the August issue, came out of the “Writing Culture at 25” conference that was held at Duke and sponsored by the Journal of Cultural Anthropology and Duke University Press. At the time, I was the President of the Society for Cultural Anthropology and was invited to take part. The invitation came at this great moment for me. I had moved from the University of Chicago to the University of California, Santa Cruz, and I was finding myself in an intellectual transition. I wrote in a fit and drew on some ideas that I have been working through in my third book, which originated out of a proposal for Mellon New Directions Fellowship (which I didn’t get) that would have had me studying archeology and cognitive science while working on the origins of the grip of the idea of West Papua as a Stone Age land and what it has meant politically and how it came out of a particular colonial experience. A lot of my thinking on Hume, sympathy, and empiricism came out of this third ongoing project.

How long has this project been going on?

I applied for the Mellon New Directions in 2005. At this point I have chunks of writing that will go into a book. One chunk was in Cultural Anthropology in an essay entitled “Sympathy, State Building, and the Experience of Empire.” Another chunk is a manuscript on technology and affect that I have given in a bunch of different places. This will be a short book that will have a section on sympathy and a section on technology, sandwiched between a section on colonialism and a section on anthropology. This question of anthropology’s relationship to empiricism is something that I am working through in this book. The Writing Culture conference gave me an excuse to try out some of these ideas.

But my interest in empiricism also has to do with being in a certain phase in my career. There is so much anxious thinking that goes into the process of getting through graduate school and getting tenure. You are worried about saying the wrong thing. Then suddenly you get to a place where you aren’t any more. Obviously it matters if you are wrong and you don't want to be wrong. But when you have tenure you have the privilege, which is the fabulous privilege of our career, of being able to try out ideas, of having ideas that are hypothetical and a little bit playful. This playful sort of thinking has been pleasurable and attractive to me in recent years. Another thing that's been pleasurable and attractive to me is the possibility of embracing an ethics of intellectual generosity instead of intellectual hostility. I like the idea of thinking along the lines of “what if?" instead of presuming that if we are reading something it is only to cut it apart. I am really over intellectual hostility. I don't think it is very productive. The alternative doesn't mean just accepting everything. It means being willing to read constructively, productively, and reflexively. It means recognizing that there are different viewpoints on the world.

In the paper, you discuss the ethical challenges and obligations to “act” deriving from the empirical nature of fieldwork, but you seem to have reservations about using the term “political” to name such acts and commitments. Is this a conscious choice?

I don’t like citation dropping but I will answer this question by talking a bit about Derrida. I find Derrida’s reflections on the ethical really powerful because, in a very dizzying and liberating way, he undercuts foundational notions and breaches the no-fly zones that protect things we take for granted in order to think. His is a reflexivity of the most rigorous kind. It involves recognizing that one still has to act in the world and inhabit an ethical position. If there is justice it can never be following a program. It can never be something that one gives or provides or does from any sort of self-assured position with a lot of good conscience. This is one thing that really attracts me about the notion of the ethical: that one can only be ethical by giving up agency, or giving up the myth of agency and the myth of control. Somehow the notion of the political does not quite capture this. For me, the word has a different resonance. Although there are different ways of thinking about the political, it is often brandished as a critique, as a way of saying “this is apolitical as opposed to political" or “I know what political is and I am political in these ways.” When you talk about the political, you think of the polis, the public, all the ways in which communities of concern have been conceptualized in western intellectual thought. Of course the term has been transformed in many ways including through the phrases like “the personal is political.” But even the terms public and private have resonances we need to think about.

The ethical by contrast concerns what one owes the other. As Derrida insists in his discussion of Kierkegaard in The Gift of Death, one is always in this position of irreducible debt. In one's indebtedness to one other, there are always “other others”. So the ethical also leads us into the question of the “other others,” which, I think, is directly related to the question of how to work in West Papua. You cannot just write this exposé about something that happened in a way that will make a big splash and feel good about yourself. You have to think about the “other others,” especially if there are people who are your interlocutors and could be really damaged by the language you use to do this. It’s not just the politics of your practice but also the ethics that you have to think about

Can you then talk briefly about where you see your own research in West Papua in terms of the kind of empiricism you call for and its temporal and ethical implications? What kind of obligations and action did such research generate for you as an anthropologist and what kind of transformations have such obligations undergone in time?

West Papua is a place with a tragic history that is at the same time filled with hope. I am confronted by almost uninhabitable ethical demands by virtue of working in this place. You can never fully satisfy these kinds of demands and yet you have to try. One way you try is by thinking rigorously about all the kinds of audience that you want to speak to and your relationships with these audiences. You end up thinking about how you can make your work speak to policy makers and politicians and other people in positions of power who might be able to make things marginally better. The ethical situation of the anthropologist not only concerns what kinds of research we are doing, what we are thinking about when we are doing it, and what kinds of data we are collecting. It also concerns what kinds of writing styles we embrace, what sorts of collaborations we entertain, and what sorts of authority and power different kinds of arguments have in different places.

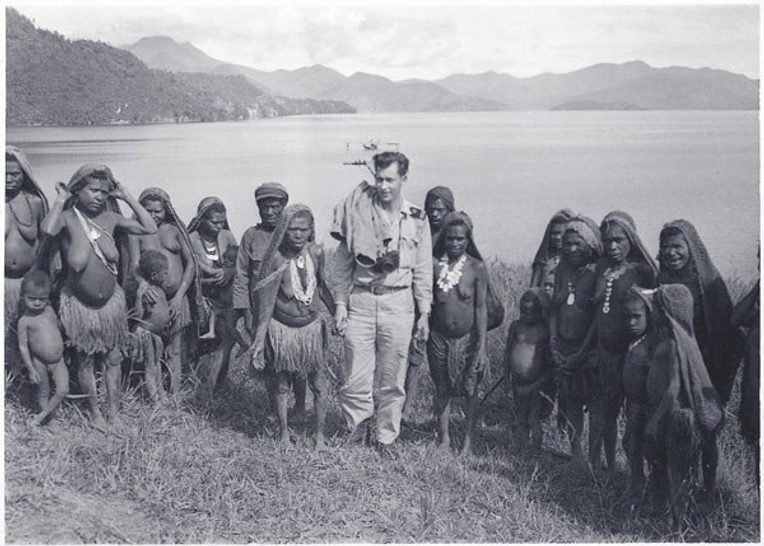

One of the tragedies, but also one of the blessings, of my life is that I have a disabled daughter. I am also a widow. These two facts have made it difficult for me to get back to West Papua to do the kind of fieldwork that I went into anthropology in order to do. This is hard for me because I feel distant from people from my dissertation research I feel very indebted to. People in Biak were generous to me beyond compare; they let me follow them around and talked to me about difficult personal, political, and historical things. Since I can't get back there, I have trouble fulfilling the obligations I feel. But any time I am invited to do something where having an academic on hand might help, if I can at all do it, I will do it. So I have gone on some lobbying expeditions in Congress, and I have worked on some policy related projects, because I had West Papuan interlocutors who told me "yeah it would be really helpful if you did this.” My work on the colonial archives of the 1930s might seem distant and its connection to contemporary matters might be a little more tenuous. But the racist romanticism that comes out of this stuff from the thirties has been key to the ongoing ability of people to completely overlook the sort of treatment West Papuans have gotten. Even if my third book doesn’t reach policy makers, it might be able to reach people who can reach these people. At the very least, it should trouble readers’ understandings of this part of the world as the place where Stone Age tribes live.

Can we say that Hume’s writings on the relationship between inference, experience and expectation provide us with the ingredients not only of a kinky empiricism but also of a new temporality in which anthropologists do not only situate ethnography in a specific time-space but also inhabit the same world of emergences, memories and anticipations with their interlocutors?

I think temporality is very important in relationship to the kind of empiricism I am talking about in this paper because an anthropology that is empirical is an anthropology that is rigorously historical. It is an anthropology that is always concerned with presuppositions and entailments. The impossible moment of the passage from what is presupposed to what is entailed creates further conditions for action. Going back to Derrida, the present is never really present. One is never living in a present moment in the sense that there are ever only moments under erasure. One gets to the end of a sentence, and one will have known what the start was all about. Hume's notion of experience inscribing itself also seems like a powerful way to think about looking at an ethnographic moment. Hume provides a powerful way to capture the trajectories passed through by the different humans and objects that are involved in this moment, trajectories that leave marks and shape expectations that then come into the mix to create experiences that shape further expectations.

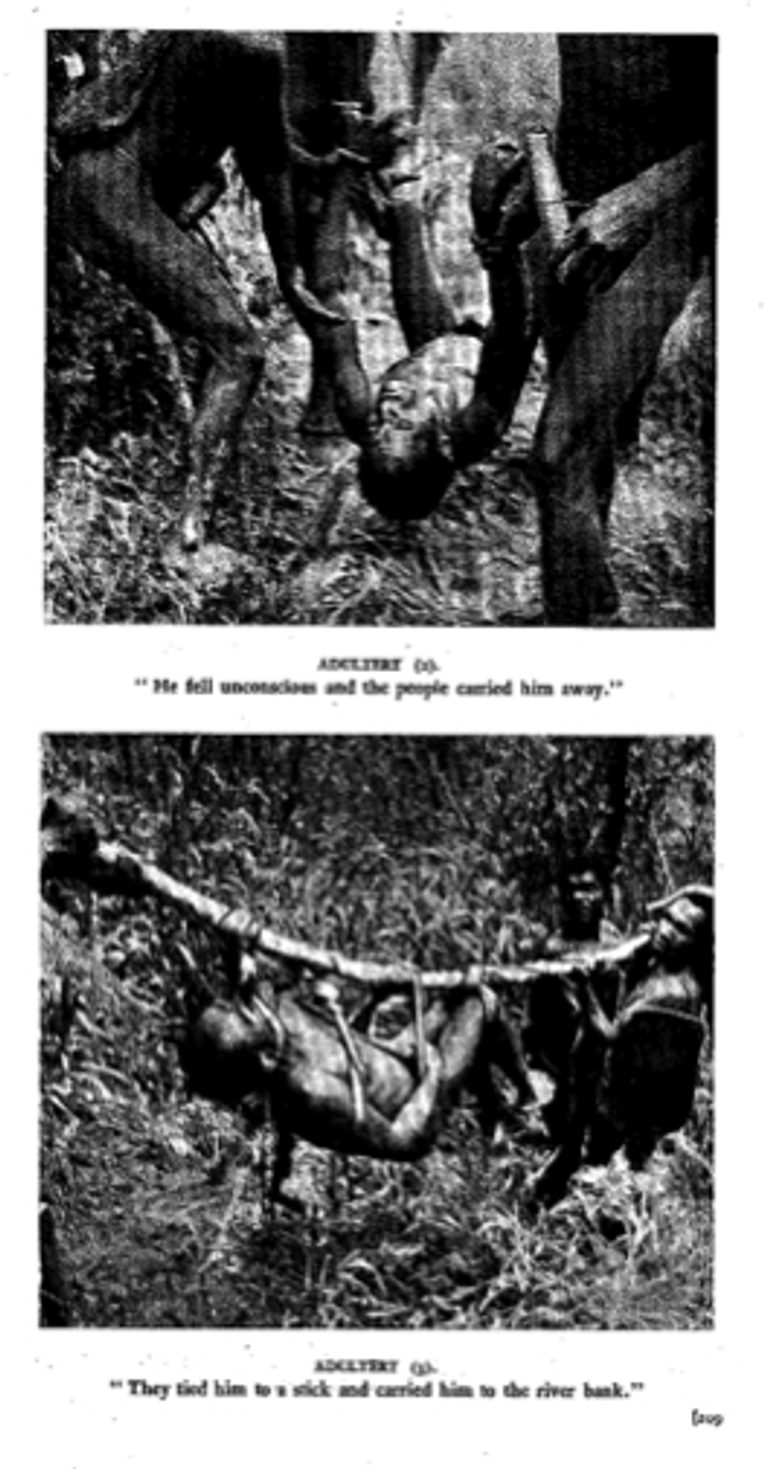

There is an ethical side to this sense of temporality in relation to West Papua as well. There is clearly a politics of time. The disquieting vulnerability that came out of sympathizing with the Papuans gave rise to this notion of the Stone Age. The Dutch imagined the Papuans as belonging to a different time as a way of bracketing this experience of sympathy and making it manageable. But one should also think about all the different pasts, all the different starting points and ending points that are envisioned, and that come together to shape future actions. We should be attentive to inter-temporality, differences in and connections across time. Rupert Stasch writes brilliantly about inter-temporality. What is it to be among others who preexist you and among others will survive your death? I think this sort of thing happens in relationships with texts as well. Reading someone like Hume leads you to think about the particular circumstances that might have gone into shaping a text. But these circumstances also produce possibilities that continue in the text’s afterlife and are projected into the future. Although it is important to critique the ways in which others have been conceptualized as belonging to different times, we should not sacrifice a notion of differences within time in order to make that critique.

Are the forms of proximity and distance embedded in writing processes different than those established or experienced by anthropologists in the field? Can we talk about forms of sympathy that do not involve occupying the same physical space or moment with the sympathized?

Hume talks about sympathy in terms of proximity, but also in terms of inference. Sympathy always involves a process of sign reading. You encounter another and perceive an embodied reaction, you infer a cause and in going through that imaginative process of inference you reproduce the cause in yourself. So in a sense this imaginative sign reading results from proximity because it takes place in the space where your body is situated in relationship to the signifier, which can be the bodily gestures or even the smell of the other. Yet sympathy is also always semiotic the whole way down. So, the sign involved can also be a text. Deleuze’s reading of Hume on empiricism and subjectivity points out how sympathy for Hume is essential to governance and sympathy at a distance through artifices is one of the ways in which governance works. So there is a place for text already built into Hume’s notion of sympathy. This has to do with the way he thinks about inference, science and semiotics. Sympathy is always about expectations and reproduced embodied experiences. It certainly makes a difference how something gets mediated, and I am not saying that where bodies are situated in relationship to one another doesn’t make a difference. But it is not like there is this gap between the face-to-face and the written within Hume.

Similarly when you do fieldwork you realize that your anticipated writing is intervening in your experience all the time. This is one of the things that is really fun about fieldwork. You are there but you are not there, all the time. We are always there and not there whenever we are doing anything in relationship to a certain practice of writing that shapes what our experiences are. The modality of mediation through which one deals with different sorts of material conditions of sympathy is very important to think about. So, I am not saying that there is no difference between writing and face-to-face interaction. I am saying that there are analytic tools that can allow you to explore the distinction in a way that doesn’t put writing and face-to-face interaction into different conceptual boxes.

The title of your article captures your call for reclaiming the “empirical” as a valid anthropological way of knowing the world as well as the necessity for re-formulating the terms and content of empirical research from an anthropological perspective. Can you tell us how you came up with the term “kinky” and why it seemed more appealing to you than, let’s say, reflexive, ethical, skeptical, situated, or passionate?

This was a paper where I knew exactly what title it would have even before I had a clear idea about what the paper was going to be about. When I asked myself “what kind of an empiricism is it that I’m interested in?” my answer was already: “This has to be kinky empiricism.” It was very intuitive. The title came out of nowhere. But by virtue of your question I now am trying to think of where it came from. I have to say that it might have to do with the sex columnist Dan Savage who writes a column in the Onion called “Savage Love.” Dan Savage uses the word “kinky” a lot. He is incredibly ethical, even a little bit moralistic. But at the same time he is incredibly capacious in his understanding of the range of possibilities when it comes to intimate relationships. He had a column the other day about this guy who was involved with a woman and did not self-identify as someone who loved men but had this fantasy involving men that he really got off on. Dan Savage’s response to him was important in a broader context. He said, “Everyone has a kink, everyone has a desire for something that seems kinky from the perspective of someone else.” Going back to biological anthropology and human evolution, he made the point that human beings have big brains, they make lots of connections, they have a great capacity for language, creation, technology and different ways of inhabiting the world. Differences in sexual orientation and modalities of pleasure are all part of the same package. If there is anything natural about humans, it is precisely variety. What Dan Savage is doing with “kinky” is like what others have done with “queer.” He is recapturing the insult and turning it into something that is useful in retooling the notion of human nature. And he is taking an ethical position by saying that it is wrong to impose one’s notion of the norm on someone else. So although I had this intuitive and impulsive attraction to the term, the more I think about it, the more sense it makes to me. Kinky is something that is playful and perverse in a way that is tolerant of other modes of perversity. For me the term was a useful entry into Hume since he is perverse, playful, skeptical, and tortured, and often all of these things all at once.

What then does “kinky empiricism” as a consciously taken position entail for the anthropologists? Do you think the forms of engagement with lived reality invoked by kinky empiricism go beyond what is demanded in the calls for public and/or applied anthropology?

Kinky is just an extension of perverseness in general. Maybe I’m just looking for a new way to be perverse. Still, I do feel strongly that there are stakes in being able to have conversations across disciplinary boundaries. Not just the boundaries that have been easy and tempting, such as the cross-fertilization between anthropology, philosophy, literary criticism and other fields in the humanities. Not just the boundaries now being crossed by environmental anthropologists, who have ventured into the hard and natural sciences, as well as the humanities. All of this is exciting. But we have been more hesitant about engaging with the others that are closer to home. What about biological anthropology for instance? And what about sociology, economics, or psychology? How do we think about our relationship with not only the ethnographers in these fields but also people doing quantitative research? We have to think about which sorts of disciplines are closer to the armpits of power in U.S. or Canada or wherever it is that we are doing anthropology. Given that there is a certain privilege given to certain kinds of methodological approaches, how we situate ourselves in relationship to these fields is a politically important question for a public anthropology –and all anthropology is public on some level.

There is always a projection of one’s own experience involved in writing this kind of essay. In the end I do what I think is fun. I think about what kind of thinking I want to do with the time I have in the planet, what kind of problems I want to explore, and what kind of challenges I want to face. If you want to come with me on this trip, fine, let’s go together. If not, that’s fine, too. I am sure that whatever you do, I will find all sort of things in it that I admire, not least of which is the fact that I am not sure that I can do it myself. Of course, if you want to do what I’m proposing we do, you will need to find people who are willing to converse with you. You will need to be among people who are willing to accept that there are different ways of looking at a problem, and different perspectives to take, which all have their own weaknesses and strengths. If doors get slammed, let’s not be the ones slamming them. I guess that would be the position I would take.

Additional Readings

Bourgois, Philippe and Jeffrey Schonberg. 2009. Righteous Dopefiend. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1991. Empiricism and Subjectivity: An Essay on Hume's Theory of Human Nature. New York: Columbia University Press.

Derrida, Jacques. 1996. The Gift of Death. Chicago: University of Chicago

Kirskey, Eben. 2012. Freedom In Entangled Worlds: West Papua and the Architecture of Global Power. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mueggler, Eric. 2011. The Paper Road: Archive and Experience in the Botanical Exploration of West China and Tibet. Berkeley: University of California Press

Danilyn Rutherford. 2010. In Defense of Ambivalence. Graduate Socialization in Anthropology, Michigan Discussions in Anthropology 18 (1):378-386.

Stasch, Rupert. 2009. Society of Others: Kinship and Mourning in a West Papuan Place. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Thorkelson, Eli. 2010. The Limits of Theory: Idealism, Distinction, and Critical Pedagogy in Chicago Anthropology. Graduate Socialization in Anthropology, Michigan Discussions in Antropology 18 (1): 324-377.