Land and the Violence to Come in Colombia

From the Series: The Colombian Peace Process: A Possibility in Spite of Itself

From the Series: The Colombian Peace Process: A Possibility in Spite of Itself

The landscape of the Caribbean coast has been transformed over the past twenty years, as vast stretches of African oil palm and other monocrops stand in neat rows, dominating the view from the roads. These dark palms are the most visible manifestation of the transformation of the past twenty years. What I want to suggest in this short essay is that how people narrate the story of those changes illuminates the violence that comes to this region.

Last year I spent months interviewing local business and political leaders on the northern coast. They know who won the war whose formal end is being negotiated in Havana: they did. Well, they did alongside the paramilitaries—vast private armies that have been funded by the illegal drug trade and have worked closely with local military commanders. The counterinsurgency that the paramilitary fighters embodied was just as much a political and economic program as a military one. Regional elites in the coast see no reason why any peace talks should force them to relinquish a portion of their spoils.

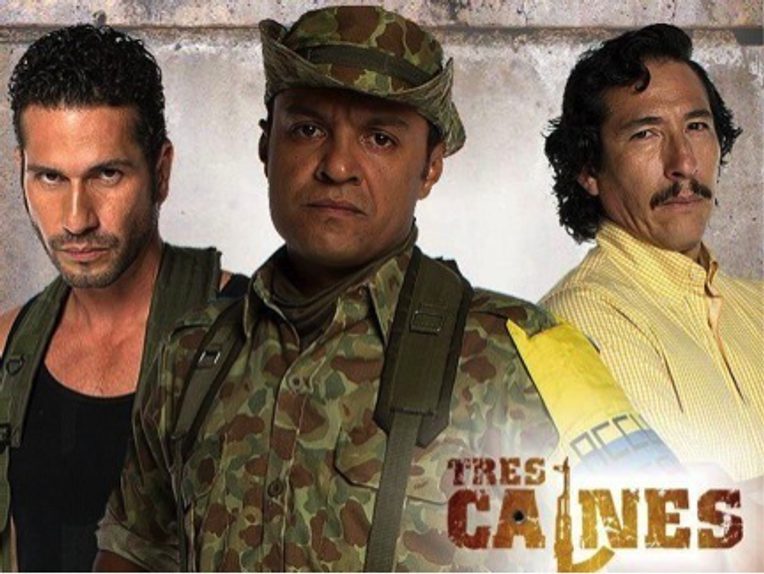

Diana (not her real name) exemplified this view. “I am on the side of the paramilitaries,” she told me in her rapid-fire coastal slur. The previous night’s soap opera, Tres Caínes, one of a new genre of narconovelas, had prompted Diana’s outburst.1 The show recreates the story of local drug traffickers turned paramilitary strongmen, Fidel, Carlos, and Vicente Castaño. Each night the episode began with a statement of the program’s origin in research and interviews. The writer frequently took to the airwaves to defend his project as making history available to the masses. And the masses were watching: the show was one of the most popular of 2013.

In the show, Carlos Castaño is the country’s savior, committing excesses to be sure but nevertheless dedicated to protecting his people. “We are making the homeland, liberating this country from forty years of guerrilla subjugation,” is a refrain he constantly growls to the troops under his command. Carlos is presented as wrought with guilt for his frequent absences from family gatherings, sacrificing the leisurely life of a wealthy landowner in the service of an underground counterinsurgency war. The show lingers in expansive detail over guerrilla abuses, with scenes of anonymous rural paramilitary victims.

Diana and other elites echoed the show’s implicit argument that the paramilitaries had saved the region from relentless guerrilla attack. She went on to tell me of her father’s vast landholdings, his multiple farms, and his decisive dealings with paramilitary commanders. He paid his “tax” to the paras in a lump sum. When regional warlord Carlos Castaño wanted to buy his prize thoroughbred, he offered it to him for free and then watched with pride as the horse appeared alongside him in media interviews.

Carlos has been dead for ten years; his replacements were either killed in infighting or extradited to the United States for drug trafficking after talks with the government led to a paramilitary demobilization process. But Tres Caínes obscures this fact and rather tells us a story about the future: a story about land, who gets it, who deserves it, and who will die for it.

The telenovela, like Diana’s narrative, is a story about who is to blame for the conflict: the guerrillas, who arrived in a feudal paradise in which the benign patriarchs of vast haciendas ruled without question. The century of violent settler colonization in the region and the brutal suppression of land reform efforts are erased in telling this classic story of “excesses” rather than one of systemic violence. It is a story that also obscures the central role of drug trafficking in both the expansion of paramilitary armies and the evolution of regional economic power structures (Romero 2011).

Land is a tortuous issue in Colombian history. Efforts to consolidate territorial control have been at the heart of much of the past century’s conflicts, and there has never been a successful land reform. Rather, Colombian scholars have described the past twenty years as a “reverse agrarian reform” (Reyes 2009; López 2010), in which millions of peasants were violently dispossessed as drug traffickers and other wealthy patrons bought up huge swaths of land for money laundering, cattle ranching, and extractive forms of “development.” Land rights and rural development were the subject of the first agreement between the government and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), announced from the negotiating table in November.

Government efforts to begin land restitution measures (President Juan Manuel Santos’s flagship program) have become a flashpoint for resurgent violence. Less than one percent of the land claims have been settled. At stake are millions of acres that are now home to extractive mining industries, extensive monoculture agrobusiness, and shipping routes for contraband of all kinds. More than twenty land-rights activists have been killed since the program began; hundreds more have been threatened. The government may get the FARC commanders to lower their guns, but their ability to reign in regional landowners is doubtful. In the firing line, now and when the formal reconciliation efforts unfold, will be those who try to undo the paramilitaries reverse agrarian reform of the last twenty years.

1. Available for viewing on the Internet via MundoFox and broadcast in Colombia from March 4 to June 18, 2013.

López Hernández, Claudia, ed. 2010. Y Refundaron la Patria… De Cómo Mafiosos y Políticos Reconfiguraron el Estado Colombiano. Bogotá: Debate.

Reyes Posada, Alejandro. 2009. Guerreros y Campesinos: El Despojo de la Tierra en Colombia. Bogotá: Editorial Norma.

Romero Vidal, Mauricio, ed. 2011. La Economía de los Paramilitares: Redes de Corrupción, Negocios y Política. Bogotá: Debate.