Moments of Lightheartedness: Graphic Ethnography Unsettling the Weightiness of Fieldwork

From the Series: Graphic Ethnography on the Rise

From the Series: Graphic Ethnography on the Rise

My research and publications for the last two decades have ethnographically explored the public memories of wartime sexual violence of the Bangladesh War of 1971 along with writings on war memorials, museums, gendered embodiments, ethics, aesthetics, conflict related adoption, digital surveillance, and recently on irreconciliation (Mookherjee 2022). I have not written about many "happy" things[1] as fieldwork among survivors of wartime sexual violence felt fraught, fragile, and emotionally exhaustive. My collaboration with a graphic artist, and the labor invested in generating an ethnographically-inspired graphic novel, have encouraged me to revisit the artificial separation between happy and heavy anthropological themes. In what follows, I am outlining this transformation in my approach.

In an unprecedented move till date, in 1971, the Bangladeshi interim government, referred to women raped by the West Pakistani army and East Pakistani Bengali and non-Bengali collaborators as birangonas (meaning war heroines). This bold public policy by the Bangladeshi government was a way of ensuring that the women are not socially ostracized and can be absorbed into the new nation as citizens, workers, and future mothers. I explore the complex dynamics of the public memories of sexual violence through a triangulation of ethnography among survivors, their families and communities, as well as among human rights and feminist activists along with exploring the visual and literary representations of the survivors in my book: The Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public Memories, and the Bangladesh War of 1971 (Mookherjee 2015).

One of the central findings of Spectral Wound was how survivors of sexual violence found the process of giving testimonies to be an equally transgressive process with negative consequences when ethical practices are not followed by those recording their experiences. Survivors talked to me at length about their long experiences of the non-consensual and intrusive nature of testimonial cultures. These testimonial cultures thereby became the focus of my research in the book and as a result the fieldwork process felt tense in case, I did anything which can seem to be similarly transgressive to the survivors. In numerous instances I have been asked what was the effect of this research on myself and I jokingly responded by saying my hair went sixty percent grey when I finished my fieldwork in order to avert the focus from the fieldworker’s experience of emotionally difficult fieldwork.

After the publication of my book in 2015, I was invited to speak at the Dhaka Literary Festival in November 2016 and also launch the South Asian edition of the book. I took this invitation as an opportunity to initiate the first collaborative workshop with my partners Research Initiatives Bangladesh (RIB) as well as invited participants, which included survivors who were in the public eye, academics, researchers, government officials, policymakers, NGO representatives, feminists and human rights activists, journalists, filmmakers, and photographers. The aim was to develop a set of interviewing guidelines, a graphic novel, an animated film, and a website (Mookherjee and Keya 2019) to assist those taking testimonies from survivors. Having grown up with Indian comic books, in 2016 I teamed up with a fantastic Dhaka based visual artist Najmunnahar Keya to translate some of the ethnographies of the book into a graphic novel.

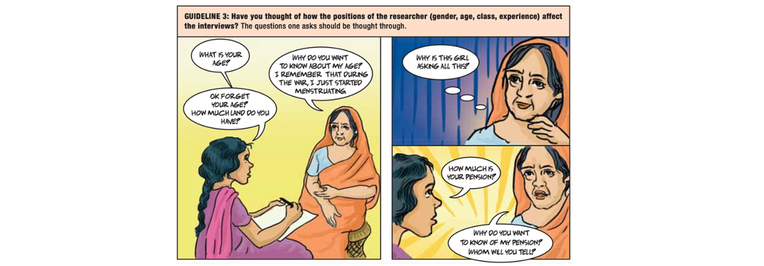

To visualize the ethnography in words as well as images was a very challenging task. I developed the story boards to be transformed into drawings by my co-author, Keya. So, we were developing a set of guidelines for professionals seeking to record testimonies of sexual violence, but as an ethical exercise. The guidelines became alive as images and the intergenerational story of the graphic novel that was scaffolding the procedures, helped us to make it a form of familial witnessing of the unravelling of the story of the birangonas. Alongside, drawing on the ethnography in the book among the survivors, we were visualizing ten ethical guidelines for those working among survivors.

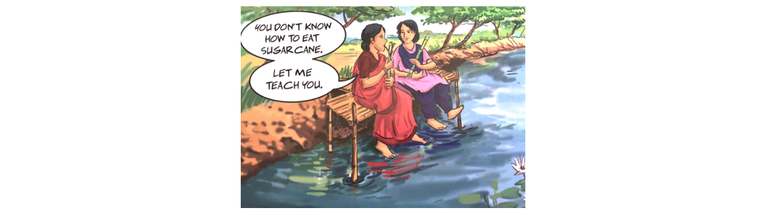

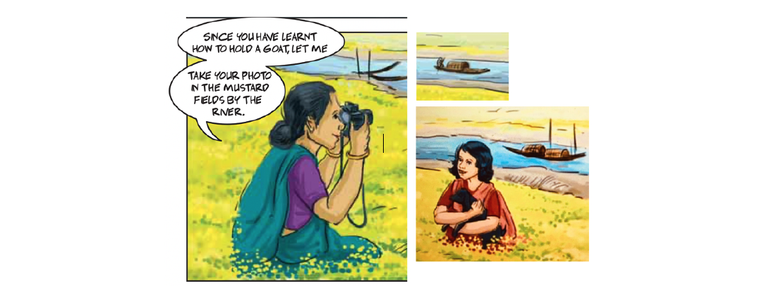

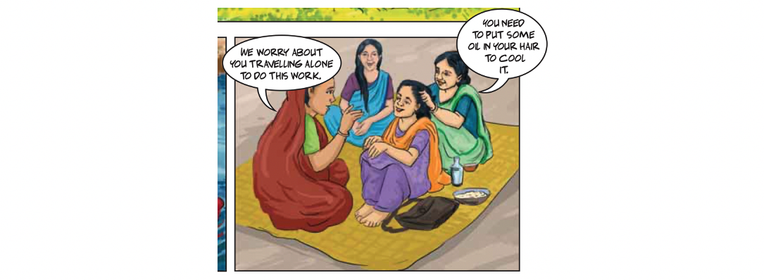

In parallel with these guidelines and the intergenerational story, the graphic novel also includes graphic images that depict moments of fieldwork happiness, which unravelled spontaneously in the midst of engaging with deeply horrific experiences of sexual violence. Looking at the way Keya was able to capture my ethnographic description of these various moments of lightheartedness, reminded me how important these various instants were during the fieldwork which otherwise felt like constantly walking on egg shells. In an almost surprising manner, the contribution of the graphic artist brought the experiences of the anthropologist forward, generating a new vantage point for analytic reflection. This was both mine and Keya’s favorite page in the graphic novel.

The sensorial dimensions of such graphic images draw me back to my arrival in the area in 1997 in the back of a rickshaw-van through picturesque harvested fields of seasonal sugarcane, rice, and mustard, which brought me to the village located on the bank of the Podda, one of the largest rivers of Bangladesh and which has stood for a pan-Bengal imaginary in West Bengal (India, where I am from) and in Bangladesh. As an Indian Bengali living next door, I was an insider outsider in Bangladesh and this was only my second visit for my fieldwork. As I arrived, Dilruba Khan’s poignant "Bhromor Koio Giya" (Bee, Go and Tell) wafted from the teashop in the village.[2] I asked someone later what the song was. The song was asking the bee to go and tell the loved one how much they are missed. That the sugarcane harvest was in full swing became apparent with the village road carpeted with dried sugarcane and the half-eaten sticks of sugarcane protruding from the hands of all the children who chased my van into the village in that late autumn afternoon. The beauty of the area and of Bangladesh as this gorgeous riverine, pastoral, green country always makes me affectively yearn to go and revisit friends in the cities and villages.

In my publications I have not used the photographs of the survivors, but I have many albums of us having fun. Also, during the fieldwork my role as a photographer became well-established. When there was any occasion in the village, I would be asked to come and take photographs which I would then take to the nearest sub-town to process and bring back copies for the specific individuals and families. One day, one of the survivors said she wanted to take a photograph of me. It was a December afternoon and the sunshine was on our backs. I was given a baby goat to cuddle and made to sit among the mustard fields against the backdrop of the beautiful Podda River, its boats and the boatmen singing boat songs or the Sufi poet Lalon Fokir’s songs. The evocativeness of these images makes the laughters, the jokes, the teasings audible to the reader. Not only was I taught how to hold a goat, the survivors laughed at me and teased me for not being able to eat raw sugarcane effectively. I remember distinctively the happiness of the afternoon when we sat on a bench above a pond and ate sugarcane as depicted in the image.

Survivors would also lament that I am far from my family, traveling across different spaces on my own and yet I don’t oil my hair. Oiling one’s hair is a sign of well-being and of being looked after. They would often make me sit down forcefully to oil and massage my hair. They would say they worry when I am traveling alone. One afternoon as they sat oiling my hair and chatting, a man passing by said to the women that I must be careful not to leave my jaat in the village when I return back home. Immediately, there was a weighty silence among the women. As the man walked by smirking, the women whispered that he just cautioned you, threatened you because of what happened to us during the war. "Leaving my jaat in the village" refers to a possible attack on my sexuality as I am there on my own. The violence of this statement in front of the survivors adds to the multiple weightiness of this expression. Given the national exposure of the women as survivors I had not asked the women about their experiences and only relied on what they wanted to talk to me. During another occasion of having fun in a summer afternoon and swimming in the village pond in my thick black and white salwar kurta (which I had kept for swimming purposes), one of the survivors told me that, "that day" she had hidden in the pond. My immediate inane question as to how she was feeling was also a sense of shock of what she had just told me. She did not want to stay in the pond anymore and instead we go out to get dry and drink some black tea together by her earthen oven.

The memory of happiness and humor, the touch of affection and poignancy of the survivors on these pages reminds me how significantly aesthetic, sensual, and emotional these images are. Rather than showing the birangona as an oft-imagined horrific figure, the playfulness of the survivors brings out her liveliness and is part of the forging of a social change to understand who the birangonas are, what are their socialities of violence and toxicity in the everyday? The pond reminds the survivor of "that day" and she can’t avoid seeing the pond which is next to her home.

The graphic images also disrupt ethnographic authority. The survivors laugh at the ethnographer, tease her for her lack of hair oil, or her inability to learn to eat raw sugarcane or to hold a goat. The gaze of the survivors are on the ethnographer as the latter is made to sit and pose for photographs. The affective interpretation, feeling and understanding enabled by these images might allow some poignant author-reader-interlocuter dynamics and enable the reader to pause, contemplate and reflect on these images of happiness and play, humor and affection to rethink who a survivor of wartime sexual violence is. In this non-textual respect, graphic ethnographic experimentation enabled a reversal of the ethnographic gaze, which made the ethnographer more visible, while taking away the emotional pressure from the survivors.

[1] To date, only two of my publications, on clothes and food, were about pleasant themes. One was on sartorial practices during fieldwork (Mookherjee 2001) that came out in Anthropology Matters when I was a PhD student. The other was a piece on culinary boundaries (Mookherjee 2008) that was published in special issue on food in South Asia.

[2] I was working in "a village," not as an anthropological yardstick. Many survivors who had testified publicly lived in this area.

Khan, Dilruba. 2018. "Bhromor Koio Giya (Bee, Go and Tell)." Youtube.

Mookherjee, Nayanika. 2001. "Dressed for Fieldwork: Sartorial Borders and Negotiations." Ethnography@TheMillenium: Anthropology Matters, June 2001, Issue 3 (June).

Mookherjee, Nayanika. 2008. "Culinary Boundaries and the Making of Place in Bangladesh." In "Food: Memory, Pleasure, and Politics in South Asia," edited by Caroline Osella. Special Issue, Journal of South Asian Studies 31, no. 1: 56–75.

Mookherjee, Nayanika. 2015. The Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public Memories and the Bangladesh War of 1971. Durham N.C.: Duke University Press.

Mookherjee, Nayanika. 2016. The Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public Memories and the Bangladesh War of 1971. Dehli: Zubaan Books.

Mookherjee, Nayanika, ed. 2022. "On Irreconciliation." Special Issue, Journal of Royal Anthropological Institute (JRAI) 28, S1.

Mookherjee, Nayanika, and Najmunnahar Keya. 2019. Birangona: Towards Ethical Testimonies of Sexual Violence during Conflict. Durham: University of Durham.