Not Another Polytechnic Occupation! Reading the Graffiti on the Athens Polytechneio, March 2015

From the Series: Greece is Burning

From the Series: Greece is Burning

The Polytechneio—the old neoclassical complex of the National Metsovio Polytechnic University on Patission Avenue in Athens—is a charged space, a topos of Hellenism (Leontis 1995, 18) for most Greeks. For decades, its exterior walls have been covered with banners, posters, and graffiti, while protesters frequently occupy its inner spaces. The consistent message of the buildings’ serial extracurricular uses has been the resistance of freedom-loving Greeks against political oppression. This has been the most common reading of the buildings’ occupations, at least by people positioning themselves on the progressive half of Greece’s broad political spectrum. Then one day in March 2015, a huge back-to-back, black-and-white graffiti piece claimed the two most visible external walls of the Polytechneio building on the corner of Patission and Stournari Streets with an inscrutable message.

A black background of high-quality plastic paint covered the two walls’ every nook and cranny, leaving just the Doric entablature and pediment unpainted. Everything was painted black: windows, decorative marble detailing, nearby street lamps, even sidewalks. Against this black surface, shaded white and gray wheel-like designs and serpent-like, monstrous shapes—sometimes recognizable as Solaris-style aliens, at other times dissolving like salt crystals into chaos—moved in irrepressibly sweeping gestures from one corner to the other.

The piece had a powerful effect. People were shocked by its magnitude and darkness. Despite the general unkemptness of the building, with layers of air pollutants, posters, and numerous graffiti tags having accrued for years without sustained public objection, on this occasion a majority of the public (over 60 percent) identified the graffiti as a defiling event. Even representatives of the recently elected left-wing party Syriza—which generally supports free speech, especially in the neighborhood of Exarcheia—saw the graffiti as sacrilege against a monument of Greece’s democracy, not as another statement of resistance.

Why did this graphic intervention stand out in crisis-ridden Athens, known as a world mecca of graffiti for the sheer volume and quantity of work that passes unnoticed? How did it gain attention at a site both riddled with graffiti tags and saturated with political messages? Here I probe the signification of the Polytechneio graffiti piece by adapting for the examination of public art a line of thinking I developed in Topographies of Hellenism(Leontis 1995) to map out the entanglements of literature and the charged spaces of Hellenism. I work through four key points on the functioning of graffiti in the cultural landscape of the city to read the piece as an act of contentious politics (Waclawek 2011; Kornetis 2013): a disruptive artistic event that challenged meaning and transformed the social and political topography of Hellenism.

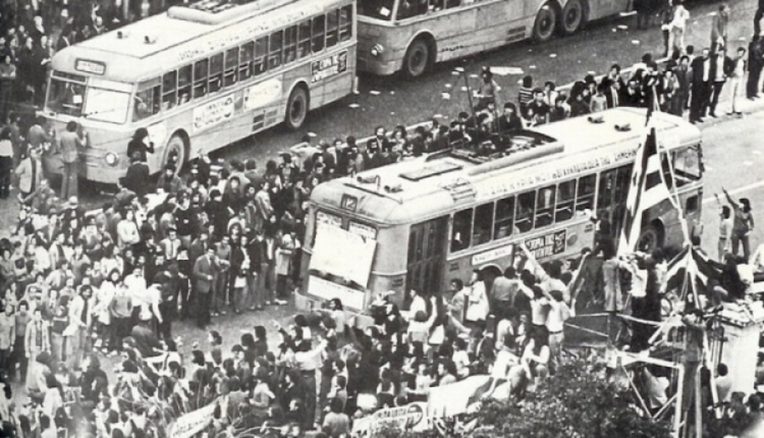

1. My first point is that the graffiti must be recognized as an overwriting: a visual sabotage of the thing it covered over. But what, besides the posters and graffiti already covering the wall, was the graffiti overwriting? The artists had chosen as their art spot a building identified since November 1973 as a political hot spot. On November 14, 1973, some three hundred students from the Polytechnic and Law School entered the building complex and occupied its three buildings to protest the dictatorship that was ruling Greece, then in its sixth year. They created a pirate radio station to invite Greeks across the country to join them, using the call sign, “Εδώ Πολυτεχνείο! Εδώ Πολυτεχνείο!” (Polytechneio calling! Polytechneio calling!). Over the next two days, busloads of protesters accepted their invitation. About ten thousand people gathered in and around the school’s gate on Patission Avenue to take their stand against the dictatorship, paralyzing traffic. In the early morning hours of November 17, the fourth day, the dictatorship deployed army tanks outside the Polytechneio gate to press the protesters into submission. Then one tank crashed through the gate into the building complex. The army violently overpowered the protesters. For all these years, since the return of democracy on July 24, 1974, the Polytechneio has been a memorial site for those who suffered or died during the student occupation. The power of the memory of their violently defeated stand has been harnessed repeatedly by all subsequent occupations, as well as the politicians who lay a memorial wreath on the site every year on November 17, now a national holiday.

Was the giant black-and-white graffiti an overwriting of the dirt, grime, artless graffiti, and national ceremony that were hanging on the building, in an artistic effort to recover a rawer sense of the original youth-led mobilization? Or was it an overwriting of the memorial, in an attempt to wipe out the significance of the student occupation forty-two years ago, as representatives of the Syriza government claimed? According to one clever tweet responding to the graffiti (which played with the most resonant meme of the Polytechneio occupation in 1973), the graffiti’s message about the Polytechneio occupation has many facets: “Εδώ Πολυτεχνείο, εδώ Πολυτεχνείο. Εδώ οι 50 αποχρώσεις του γκρι”(Polytechnic calling, Polytechnic calling. Calling Fifty Shades of Grey!). Part of the piece’s power lies in its inscrutability: it is impossible to decipher.

Undoubtedly the graffiti was an overwriting of the architectural structure: the neoclassical building designed in the 1870s by Lysandros Kaftantzoglou (1811–1885). Thus most critics identified it as an act of vandalism involving damage to a historical monument. For example, Greek painter Alekos Fassianos, in an interview that appeared in many papers, stated that any piece of art destroying another work destroys its own artistic aspirations. This graffiti, like all graffiti, destroyed the building it covered, and this was a sign of the crisis in the artistic conception of graffiti. Nikos Xydakis, the minister of culture and a journalist who was once a student of graphic arts himself, read the graffiti as a representation of the crisis of the Polytechneio in present-day Greece: “Its darkness rises out of the microclimate of the neighborhood. At the same time, the graffiti has aggressively occupied [the Polytechneio] and vandalized an architectural monument, disfiguring it and challenging its historical meaning. Besides this, it has damaged the building’s marble.”

2. My second point follows from the distress registered by these critics over the overwriting of the neoclassical building. Graffiti is site-specific work that speaks with visual language. Not only its impetus but also its imagery is dictated by topography and political geography. From a superficial viewpoint, site specificity seems to be contradicted by the negative reaction people had to the graffiti on this particular site. As observed by Xydakis and other commentators, the dominance of black on the particular neoclassical historical and political monument exerted a profoundly negative force. People were shocked by its darkness. They could not understand how such a big, black work had appeared out of nowhere. (It was soon made known by a spokesman of the artist that a small crew of artists, self-identified as Icos&Case and dressed in the workwear of the city’s street employees, had thrown it up in clear public view over the course of three days.) They felt the piece did not belong. A closer look, however, brings attention to the care of the graffiti’s design in relation to the site. As stated by a street artist colleague, the graffiti artists had worked from a careful plan.

The artists’ attention is borne out through a careful reading of the piece. As mentioned above, the artists, working quickly, applied an underlying black layer of paint to cover everything: windows, decorative marble detailing. Yet, with attention to the building’s neoclassical design, they did not cover the white pediments or Doric entablature. Indeed they marked the boundary beneath the entablature with precision. The whiteness of the triglyphs and metopes thus retained the signification of the building’s neoclassicism and offered the new work a dramatic stylistic frame. Under the building’s decorative features, the wheel-like designs, serpent patterns, and forms of monsters and fallen heroes suggested a giant frieze with a post-apocalyptic fantasy subject. Its black and white figures also called to memory black and white photos of the 1973 Polytechneio occupation. The visual commentary of the graffiti radiated beyond the building to the surrounding neighborhood, according to Alexandros Papadopoulos, a media and communications specialist. Parts of the black-and-white imagery functioned as the negative of “the stores across Stournari Street that sell comic books, tattoos, and electronic and role-playing games, and postmodern, post-apocalyptic graphic materials . . . and particularly the legendary Solaris Comics store on Botasi Street.”

By linking the graffiti’s presence to the visual and architectural topography of the site, we can account for its shock value. We recognize that the piece was not an unthinking instance of vandalism but a deliberately disruptive act. It occupied the Polytechneio in a way that transformed both the site’s classical look and its signification. The monochrome, epic-sized re-presentation of that political contest reshaped the neoclassical structure using the visual language of the twenty-first-century graphic novel to delineate a postmodern reiteration of the contest of civilization and barbarism. The ominous mythological imagery in contrasts of light and dark captured the viewer’s gaze, overlaying signs of fallen extraterrestrial heroes on the memory of students’ shouting freedom slogans from the very same building’s windows. It deterritorialized (Leontis 1990, 38; Leontis 1995) the Polytechneio as a political topos of Hellenism.

3. The third point I wish to work through is the passionate debate surrounding the graffiti. Graffiti on public walls is always controversial, never more so than when a graffiti piece attracts intense scrutiny. By making a statement in a public space, it becomes a site of the dissemination of public debate. The discourse surrounding this piece was unrestrained, as is evident from some of the comments I have already quoted. This discourse is worth exploring a bit further, as it tried to locate the meaning of the work in the cascading effects of the Greek crisis and the state’s inability to control it.

Different modes of crisis thinking wove their way through people’s comments as they shifted the target of blame for the graffiti’s appearance. The rector of the Polytechnic, Yiannis Giolas, explained his inability to prevent the graffiti as a sign of the debt crisis’s debilitating effects on his delivery of education (he could barely pay for electricity and so could not afford to hire guards) and the broader decline in the civilized behavior of young people, who no longer respected even a monument dedicated to their precursors’ youthful uprising. For journalist and architecture critic Nikos Vatopoulos, the graffiti was a huge, rock-solid (συμπαγές), aggressive work of outward-facing impudence (εχωστρεφή αυθάδια), representing the breakdown of the rule of law and a crisis of management of not only the space of the Polytechneio, but all of Athens: “No political leader, no rector, no local government has been able to contain the nonstop vandalism or even to make a realistic suggestion.” Panagiotis Sgouridιs, a deputy of ANEL (Syriza’s right-wing partner in the coalition government), reached beyond Greece to assign blame. He pushed aggressively against the work’s color scheme to unearth an unbearable foreignness, suggesting it was made to German orders: “Right now Greece is standing in resistance [to its European partners], yet [these artists] introduce a Berlin-style work with Berlin grayness against the blue skies of Athens!” His interviewer’s question, “Do you mean to say the graffiti was ordered by Merkel?”, remained unanswered.

While critics of the graffiti refused to acknowledge its artistic merits and focused instead on the crisis of order that produced it, supporters used the sophisticated language of cultural studies to relate the piece to the eminent tradition of representations of civilization’s critical other—its barbarism (βαρβαρότητα)—in order to declare it a masterpiece:

The Marquis de Sade, Jean Genet, even ancient drama would not have existed if people respected rules and order. Ancient tragedy was born from disrespect in a Dionysiac ritual: a man stepped out of the chorus and began to speak, another replied, and the dialogue created the plot. Disrespect for conventionality bore a new form of sacredness. Convention (nomos) and art are in a continuous race between them, creating new life events, forms, knowledge, and experiences, and changing the ethical dimension of the aesthetic. These social, psychological, and anthropological references enable us to read the graffiti as a triumph. [It] is exceptional not only because it refers to the novel experience of the crisis but also because it subsumes [this] tradition of interpersonal experiences and aesthetic expression: it joins modern and ancient forms scientific and social fantasy.

Dimitris Maniatis summarized the back-and-forth exchanges of the supporters and opponents as a battle between graffiti worshippers and graffitoclasts, and it is evident that there was very little communication between them. The graffitoclasts drew the most media attention and, within a few days of the graffiti’s appearance, state prosecutor Elias Zagoraios ordered an urgent preliminary inquiry to find the artists. In six weeks, the two walls of the building were buffed, restored, and covered with a protective substance against future graffiti. Interestingly, neither supporters of the work nor the anonymous spokesman who conveyed the message of the artists tried to stop the graffiti’s erasure. The artists reportedly felt that their work had fulfilled its mission.

4. This leads me to my fourth and last point. Graffiti dwells in a volatile context. Each piece of graffiti entering public space becomes a layer in the palimpsest of the city. One day it overwrites something and so transforms a wall, as the graffiti transformed the Polytechneio complex; the next day it may be buffed or overwritten. This does not mean, however, that it is made to disappear. As a layer in the palimpsest, it enters into the site’s history, to be recalled on some later occasion in another medium, another act (e.g., Eleftherakis 2015). My interest in the graffiti was piqued after it was buffed, and eight months after its vanishing it is still etched in my (computer’s) memory. As I write this, a Google search for “Polytechneio” pulls up historical images of the 1973 occupation, including one of buses stopped in front of the complex’s gate.

As I studied the bus and the figures in the image’s center right and then turned to a photo of the graffiti, unexpectedly, the juxtaposition brought into view something like the front of a bus and the passionate gestures of people in the graffiti.

This new order of things tells me that the graffiti retains the charge it drew from its brief occupation of the Polytechneio building. It may continue to function as a contentious act, disrupting business as usual, becoming a matter of concern, generating public debate on the connections between art, money, society, and political meaning, and reviving the Polytechneio’s call sign, “Εδώ Πολυτεχνείο! Εδώ Πολυτεχνείο!”

Eleftherakis, Dimitris. 2015. Η Δύσκολη Τέχνη [The difficult art]. Athens: Antipodes.

Kornetis, Kostis. 2013. Children of the Dictatorship: Student Resistance, Cultural Politics and the “Long 1960s” in Greece. New York: Berghahn.

Leontis, Artemis. 1990. “Minor Field, Major Territories: Dilemmas in Modernizing Hellenism.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 8, no. 1: 35–63.

_____. 1995. Topographies of Hellenism: Mapping the Homeland. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Waclawek, Anna. 2011. Graffiti and Street Art. London: Thames and Hudson.