Our Bodies Electric

From the Series: Our Lives with Electric Things

From the Series: Our Lives with Electric Things

Jamie introduces me to one of the horses on my third visit to Epona, a horse-assisted therapy center: “You don’t use your legs to ride her. She works with your energy. You up your energy and she speeds up. Lower it, and she slows down.” Later, I watch as another horse is free schooled, that is, trained with no equipment connecting handler to animal. The horse moves around the handler in circles, shifting direction and pace in an impressive resonance with her commands. I ask how it works. “He picks up on my intent,” she replies. “I raise my energy, and he raises his. I think it, and he knows it.”

Energy constantly flows through our bodies. Electrical impulses course through neural pathways and stimulate the beating of our heart, sending hormones pulsing through our veins. At Epona, electricity also mediates communication and attunement with the horses. It entangles therapists with these bioelectrical beings that help heal their clients. The electricity itself is instrumental to the healing: “A horse can hear your heartbeat,” Jamie tells me. Horses sense clients’ distress and respond accordingly to calm their bodies.

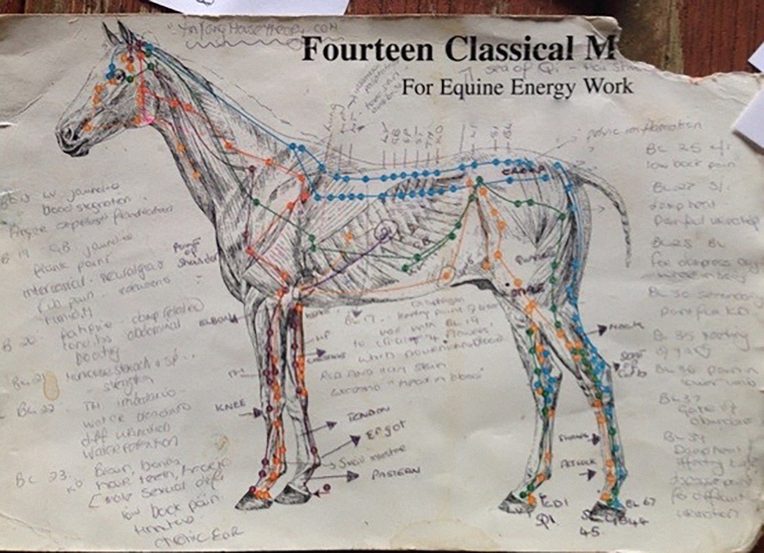

Healing goes in both directions. Practitioners maintain their animals’ health with weekly shiatsu massage, which relieves blockages in the flow of electrical impulses. Such blockages are chronic symptoms of the physical and emotional stresses of therapeutic work. The practitioner shows me her diagram of equine meridians, telling me, “We all share the same system.” Intent can be transmitted through bioelectric current, she explains: “They tell me when they need a massage. They focus their attention on me and I know.” At Epona, horses are electric. Energy is a ubiquitous vital force, the substance of a network of bioelectrical impulses that connect therapists, clients, and horses in currents of communication, intent, and healing.

When I’m feeling creative, I plug in(to) my Buchla Music Easel, a device described by its inventor as an Electric Music Box. Hands at the knobs and sliders, skin on the capacitive keyboard, eyes trained on the blinking LEDs, ears cradled by headphones: I sit and search for new sounds like Theodor Adorno’s (1998, 32) child at the piano, knowing fully well that “the new is the longing for the new, not the new itself.” But instead of new notes or chords, the box promises me the command of a more fundamental, more scientific unit of sound: the electron.

Electrons flow out of my wall socket and into the box. They are organized into periodic waveforms, filtered through resistor-capacitor circuits, controlled by voltage envelopes, activated by the touch-capacitive keyboard, and finally transduced into sound. Sometimes, when a ground connection can’t be made, I run a cable into my mouth. Wired into the box, my body itself becomes a collection of modules—fingers, mouth, ears, eyes. I become a self-governing human-machine, constituted by complex, nonlinear flows of electronic signal.

This easel holds no canvas, but rather modular electronic musical instruments. Designed in 1972—1973 by Donald Buchla, it is a scaled-down version of his larger Electric Music Boxes, which are installed across the world in universities and music studios. It reflects the popular mid-century fantasy of the miniaturized, cybernetic black box: a “suitcase system” for musicians. Forty-four years later, our black boxes are smaller, cheaper, and more ubiquitous. But they share the Easel’s assertion that sound is electronic signal, and music its aestheticized manipulation. The promises this box makes include both freedom and constraint, affordances of an electrical regime of music that is expansive in scope, but simple in dimension: action, signal, sound, and feedback, collapsed into a circuitous stream.

It is wet and gloomy outside and mountainous clouds plow by. The windows twinkle with raindrops. I, too, feel gloomy this evening. Hopping onto the bed, I switch on the hairdryer and point it at my feet. The dry heat immediately begins to warm them and the rest of my body. I leave it running for a while and enjoy its monotonous sound. It is my safe moment of the day, perhaps because it activates a key memory: I am a child, warm in bed, and my father has read a story to me and switched off the lights. My mother, breadwinner of the family, returns from work. She comes upstairs to kiss me good night before she takes a shower in the bathroom down the hallway. She then dries her hair with the hairdryer and to that sound I softly fall asleep, feeling safe, warm, and happy. When I warm my feet with the hairdryer this evening, I don’t think about these moments. I contemplate other things. But the hairdryer’s sound and warmth still make me feel safe, warm, and happy.

The hairdryer is an electric object that creates what philosopher Gernot Böhme (1993, 114) calls an atmosphere, the “peculiar intermediary status . . . between subject and object” that has affective qualities we cannot escape. For me, as for Böhme, the atmosphere is an elusive object that can be acted upon. What is needed to create its particular affective qualities, in my case, is the hairdryer. These qualities are far from intentionally designed into the hairdryer, and are highly individual. They help me connect with the circuit of my own memoryscape, one which affects me here and now. Until, that is, I have enough, as my ears begin to buzz and I switch the hairdryer off.

Adorno, Theodor W. 1998. Aesthetic Theory. Translated and edited by Robert Hullot-Kentor. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Originally published in 1970.

Böhme, Gernot. 1993. “Atmosphere as the Fundamental Concept of a New Aesthetics.” Thesis Eleven 36, no. 1: 113–26.